A surprising phenomenon has emerged in the mighty Himalayas that might slow down the effects of the global climate crisis. Scientists have noted that when high temperatures hit high-altitude ice masses, 'katabatic' winds are triggered that blow cold air to lower-altitude areas.

Comment: That may be the case, although there's data showing that temperatures at higher altitudes in certain regions of the world have also been decreasing: Extremely rare 'rainbow clouds' light up Arctic skies for 3 days in a row

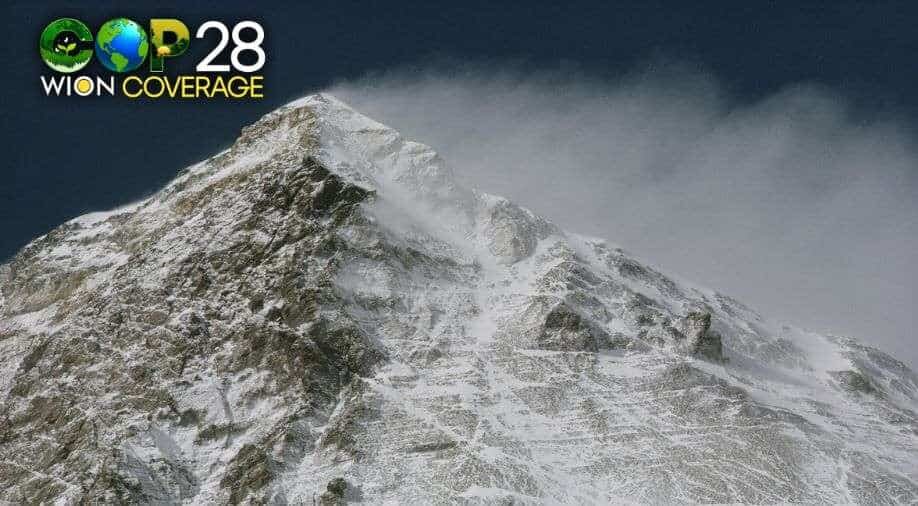

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, was conducted using data from the Pyramid International Laboratory/Observatory climate station on Mount Everest, the world's tallest summit.

What are katabatic winds?

According to Francesca Pellicciotti, professor of glaciology at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria and lead author of the study, a temperature gap is created between the air flowing above the mountains and the cooler air directly in contact with ice masses.

"This leads to an increase in turbulent heat exchange at the glacier's surface and stronger cooling of the surface air mass," she said.

As the warm air gets cooler and denser, it sinks, triggering the katabatic winds in neighbouring areas down the slope.

While this phenomenon may slow down the effects of global warming in some areas, its sustainability is not guaranteed over the coming decades.

Comment: The data shows cooling, meanwhile their models and theory forecasts warming; notably they apparently weren't able to predict this cooling phenomenon.

However, studying the impact of this phenomenon becomes vital and significant as the Himalayan mountain range feeds into 12 rivers that provide fresh water to nearly 2 billion people in 16 countries.

Comment: Which could mean a reduction in the amount of clean and fresh water available to those countries.

Concerns

Scientists noted that this phenomenon doesn't stop the melting of the glaciers due to climate change.

A June report previously covered by CNN showed that glaciers in the Himalayas melted 65 per cent faster in the 2010s compared with the previous decade, a trend highly unlikely to change its course.

"The main impact of rising temperature on glaciers is an increase of ice losses, due to melt increase," said Fanny Brun, a research scientist at the Institut des Géosciences de l'Environnement in Grenoble, France. She was not involved in the study.

Thomas Shaw, who is part of the ISTA research group with Pellicciotti, said there are various complexities involved behind the reasons for ice melting.

"The cooling is local, but perhaps still not sufficient to overcome the larger impact of climatic warming and fully preserve the glaciers," Shaw observes.

Comment: Their conclusion is that the cooling is local and that it's 'perhaps' not sufficient to counter 'global boiling', however data coming in from across the planet is showing that, overall, a period of significant cooling is upon us:

- 'Unprecedented' ice mass gain over Antarctic sheet between 2021 & 2022, outpaced mass loss

- Leading Russian polar scientist: Cooling begins in 2030...Climate crisis a 'Globalist Scam'

Also check out SOTT radio's: