An enormous volcanic comet the size of a small city has violently exploded for the second time in four months as it hurtles toward the sun. And just like the previous eruption, the cloud of ice and gas emitted what looked like a gigantic pair of horns.

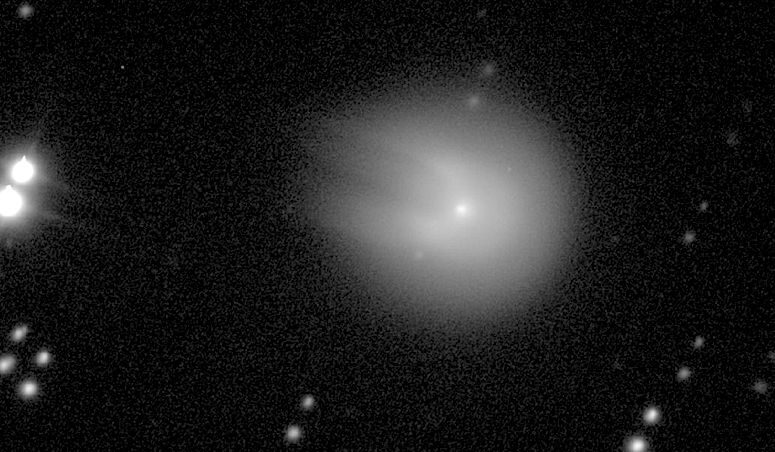

The comet, named 12P/Pons-Brooks, is a cryovolcanic — or cold volcano — comet. It has a solid nucleus, with an estimated diameter of 18.6 miles (30 kilometers), and is filled with a mix of ice, dust and gas known as cryomagma. The nucleus is surrounded by a fuzzy cloud of gas called a coma, which leaks out of the comet's interior.

When solar radiation heats the comet's insides, the pressure builds up and the comet violently explodes, shooting its frosty guts out into space through large cracks in the nucleus's shell.

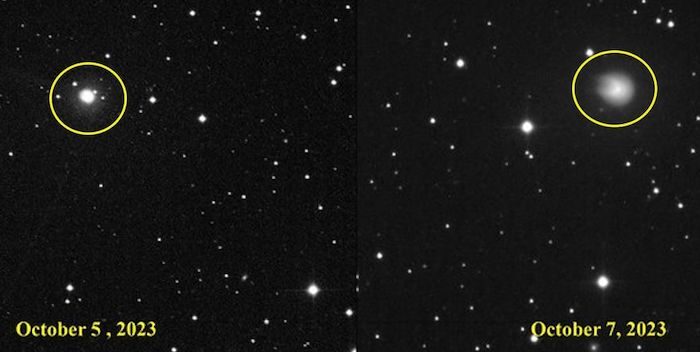

On Oct. 5, astronomers detected a large outburst from 12P, after the comet became dozens of times brighter due to the extra light reflecting from its expanded coma, according to the British Astronomical Association (BAA), which has been closely monitoring the comet

Over the next few days, the comet's coma expanded further and developed its "peculiar horns," Spaceweather.com reported. Some experts joked that the irregular shape of the coma also makes the comet look like a science fiction spaceship, such as the Millennium Falcon from Star Wars.

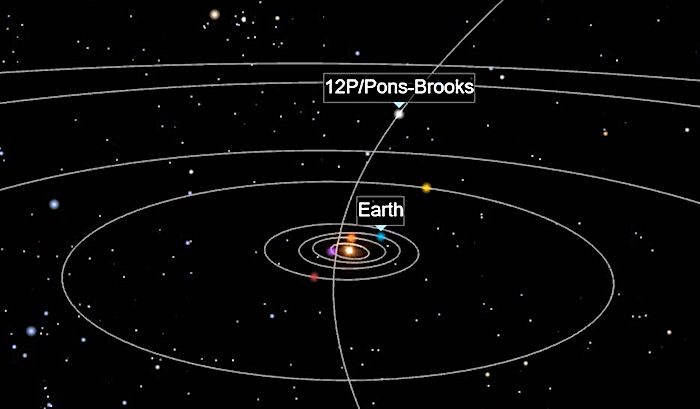

12P is currently hurtling toward the inner solar system, where it will be slingshotted around the sun on its highly elliptical 71-year orbit around our home star — similar to the green comet Nishimura, which pulled off a near-identical maneuver on Sept. 17.

12P will reach its closest point to Earth on April 21, 2024, when it may become visible to the naked eye before being catapulted back toward the outer solar system. It will not return until 2095.

This is the second time 12P has sprouted its horns this year. On July 20, astronomers witnessed the comet blow its top for the first time in 69 years (mainly due to its outbursts being less frequent and harder to spot during the rest of its orbit). On that occasion, 12P's coma grew to around 143,000 miles (230,000 km), which is around 7,000 times wider than the comet's nucleus.

It is unclear how large the coma grew during the most recent eruption, but there are signs the outburst was "twice as intense" as the previous one, the BAA noted. By now, the coma has likely shrunk back to near its normal size.

As 12P continues to race toward the sun, there is a high probability that we will witness several more major eruptions. It is possible that those eruptions will be even bigger than the most recent one as the comet soaks up more solar radiation, according to Spaceweather.com.

But 12P is not the only volcanic comet that astronomers are currently monitoring: 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann (29P) — the most volatile volcanic comet in the solar system — has also had several noticeable eruptions in the last year.

In December 2022, 29P experienced its largest eruption in around 12 years, which sprayed around 1 million tons of cryomagma into space. And in April this year, for the first time ever, scientists accurately predicted one of 29P's eruptions before it actually happened, thanks to a slight increase in the comet's brightness in the lead-up to the icy explosion.

About the Author:

Harry Baker is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. He studied Marine Biology at the University of Exeter (Penryn campus) and after graduating started his own blog site "Marine Madness," which he continues to run with other ocean enthusiasts. He is also interested in evolution, climate change, robots, space exploration, environmental conservation and anything that's been fossilized.

Good omen highlander ?

[Link]