The Tale of Carrhae's Vanished Legion

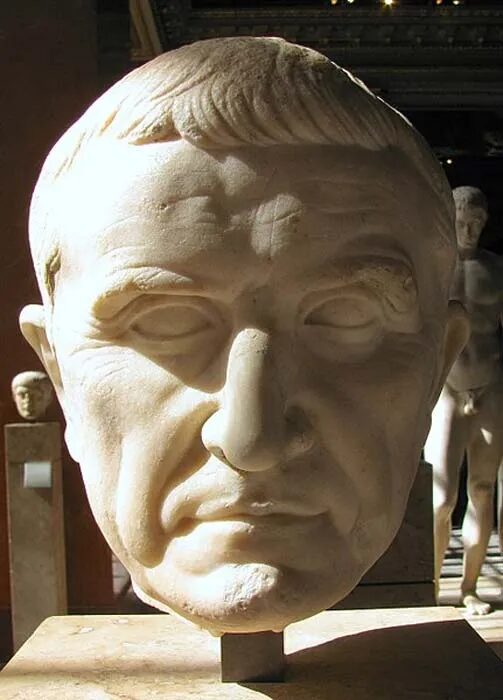

In 53 BC, a noteworthy encounter took place in Carrhae, situated near today's Syrian-Turkish boundary. This historical event involved the confrontation between the Roman commander Marcus Licinius Crassus and the Parthian leader Surena. Back then, Carrhae was a border region between the Roman Empire in the west and the Parthian Empire in the east.

Crassus, despite being extremely affluent, aspired to attain the riches of Parthia, persuading the Senate to sanction an attack with 42,000 Roman troops against the Parthian forces. However, the endeavor ended in a disgraceful loss to Surena's 10,000 archers. As Crassus negotiated a ceasefire, he met his end, supposedly through a golden liquid forced down his throat, symbolizing his greed. Additionally, reports suggest decapitation and desecration of his remains.

Following the battle, the Parthians held 10,000 Romans as captives, allegedly relocating them to the eastern bounds of their empire, possibly present-day Turkmenistan. This movement was an established Parthian strategy to garner allegiance from captives against their eastern adversaries, the Huns

Fast forward to 36 BC, a skirmish at the Han Chinese Empire's western frontier, known as the battle of Zhizhi, witnessed the Chinese contending with the Huns, their perennial foe. Chronicles from that era mention the deployment of "fish scale" formations by Hun's mercenaries, which immensely piqued the Chinese interest. The impressed Chinese officials invited these mercenaries to safeguard the border region in modern Gansu province, allocating them a designated area named Li-Jien or Liqian.

Carrhae's Missing Battalion and the Mysterious Army

The intricate "fish scale" tactic documented by the Chinese shares semblance with the Roman legions' testudo formation, spawning speculation that these unfamiliar warriors might be the surviving Roman soldiers from Carrhae's disastrous campaign who later allied with the Huns.

Historian Homer Dubs was the first to introduce this theory, suggesting that these displaced soldiers possibly opted to serve regional lords as mercenaries, instead of returning to Rome. Dubs asserted that some of these individuals eventually joined the Hunnic forces against the Chinese.

Supporters of this hypothesis pinpoint Zhelaizhai, a contemporary village near Lanzhou, as the ancient Liqian. This theory gains traction from the unique physical attributes of the villagers — like brown hair and blue eyes — and the unearthing of artifacts resembling Roman origin. Capitalizing on this lore, the village has developed Roman-inspired structures and statues to boost tourism.

Examining the Evidence

The intriguing possibility that Zhelaizhai's inhabitants might be descendants of Roman exiles has captured the curiosity of researchers globally. A genetic analysis by the University of Lanzhou partially validates the connection to European lineage, although the village's position along the historic Silk Road could explain the genetic diversity. While the phonetic similarity between "Li-Jien" and "legion" bolsters this theory, it remains contested.

Skeptics underline the formidable distance and lack of unequivocal proof as major drawbacks to this theory, suggesting the Roman artifacts could have arrived through trade networks. Furthermore, the physical characteristics and genetic makeup of the locals can be attributed to their ties with central Asian groups possessing similar features, and not necessarily direct lineage to Romans.

The Roman style pot could have been gained through trade, and the other artifacts are not uniquely Roman. Also, the physical appearance and genetic relations of the villagers doesn't require that they be directly descended from Mediterranean peoples, since there are many central Asian ethnic groups that also have genetic ties to the Mediterranean region and traits such as blonde or brown hair and blue eyes.

Even if they do have European or Mediterranean lineage, this wouldn't necessarily mean that they had to be descended from a lost Roman legion since the town is adjacent to the old Silk Road, making intermarriage with distant travelers at any time more likely. These problems do not rule out the theory, but they also leave it unconfirmed.

Another issue is that it is unlikely that the name Li-Jien is related to the word legion. Chinese scholars who have looked into the etymology of the name say that it is related to the state of Lixuan, which has connections to Ptolemaic Egypt but not to Rome. Thus, even if there is a connection to the western Mediterranean world, it is more likely a Greek connection rather than a Roman connection, according to this view.

The origin of the name "Li-Jien" too poses questions, with several Chinese scholars linking it to Lixuan — associated with Ptolemaic Egypt rather than Rome — hinting at a potential Greek influence instead of a Roman one.

The existing knowledge that Rome and China were not strangers to each other in ancient times lends a degree of credibility to the hypothesis. Despite the intriguing genetic data, the proof substantiating Roman settlers in ancient Liqian remains elusive.

The present conjecture neither confirms nor completely negates the likelihood of a Roman legion reaching China; it only clouds the certainty of such an event. Yet, the distinct features of the Liqian populace compared to neighboring regions continue to be an enigmatic aspect, inviting further exploration.

References

- Freewalt, Jason, and Joseph Scalzo. "Rome and China: connections between two great ancient empires." J. Scalzo (ed.), The Roman Republic and Empire, HIST532 K001 Spi 14 (2014).

- "A Roman Legion Lost in China" by Angelo Paratico. History of the Ancient World . Available at: https://www.historyoftheancientworld.com/2013/06/a-roman-legion-lost-in-china-2/

- " How Did Crassus Die?" by N.S. Gill (2018). ThoughtCo. Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/how-did-crassus-die-120886

- " Digging for Romans in China" by Henry Chu (2000). Los Angeles Times . Available at: http://articles.latimes.com/2000/aug/24/news/mn-9483/3

no mention of the much closer Bactrian Greek Kingdom [Link] another successor state to Alexander the Great's conquests.