A protein in the lungs that blocks Covid and forms a natural barrier to the virus has been discovered by scientists at the University of Sydney.

The naturally occurring protein, LRRC15, works by attaching itself to the virus like Velcro, preventing the Covid particles from binding with more vulnerable cells - as well as reducing the chance of infection. The astonishing find may finally explain why some people suffer serious illness with the virus, or even death, while others never get sick or appear symptomless.

LRRC15 is not known to be present in humans until the virus enters the body, but it appears after infection.

The protein helps activate the body's response to Covid and the team behind the incredible find hopes it will offer a promising pathway to develop new drugs to fight the virus.

Researchers believe that patients who died from Covid-19 did not produce enough of the protein, or produced it too late to make a difference.

This theory is supported by a separate study from London that examined blood samples for LRRC15. That study found the protein was lower in the blood of patients with severe covid compared to patients that had mild Covid.

The authors said they are now developing two strategies against Covid using LRRC15. They say the strategies could work across multiple variants.

One will target the nose as a preventative treatment, and another will be aimed at the lungs for serious cases.

Professor Greg Neely, who led the study, said his team was one of the three internationally to independently to uncover this specific protein's interaction with COVID-19. The other teams were at Oxford University in the UK and Yale and Brown universities in the US.

'For me, as an immunologist, the fact that there's this natural immune receptor that we didn't know about, that's lining our lungs and blocks and controls virus, that's crazy interesting,' Prof Neely said.

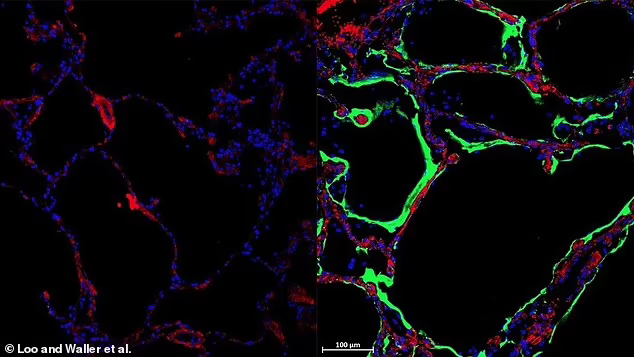

Postdoctoral researcher and study co-author Dr Lipin Loo said the LRRC15 protein was far more present in the lungs of people with COVID-19 than those without, suggesting it was already helping to protect people from COVID-19.

'When we stain the lungs of healthy tissue, we don't see much of LRRC15, but then in COVID-19 lungs, we see much more of the protein,' Dr Loo said.

'We think this newly identified protein could be part of our body's natural response to combating the infection creating a barrier that physically separates the virus from our lung cells most sensitive to Covid-19.'

The team hopes their discovery will help develop new antiviral and antifibrotic medicines to treat Covid-19, and other viruses where lung fibrosis occurs.

They found LRRC15 is also expressed in fibroblast cells, the cells that control lung fibrosis, a disease which causes damaged and scarred lung tissue. Covid-19 can lead to lung fibrosis, and it is hoped that the stunning find can help battle long Covid.

'We can now use this new receptor to design broad-acting drugs that can block viral infection or even suppress lung fibrosis,' Neely said. There are currently no good treatments for lung fibrosis, he said.

Dr Lipin Loo, a postdoctoral researcher who was part of the study, said LRRC15 'acts a bit like molecular velcro, in that it sticks to the spike of the virus and then pulls it away from the target cell types'.

'We think this newly identified protein could be part of our body's natural response to combating the infection creating a barrier that physically separates the virus from our lung cells most sensitive to COVID-19,' he said.

LRRC15 is present in many locations in the body, such as lungs, skin, tongue, fibroblasts, placenta and lymph nodes. However, the researchers found human lungs light up with LRRC15 after Covid infection.

Prof Stuart Turville, a virologist with the Kirby Institute at the University of New South Wales, praised the study.

He told the Guardian

: 'Greg Neely's team is brilliant at what we call functional genomics.The breakthrough comes as millions of Australians are told they can roll up their sleeves for a fifth Covid-19 vaccine within a fortnight, following a backflip from the nation's immunisation advisory.

'That is the ability to wake up or turn off thousands of proteins at a time and when looking at new viruses, this is really important.

'Understanding these pathways is important as they enable us to put the brakes on a virus, so other arms of our immune system can catch up and respond.

'In some cases these brakes can be so effective, that the virus may never gain momentum. Indeed this could be one of many factors that may increase the ability of people to be protected from the virus early on.'

The Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation has updated its advice to recommend anyone aged 18 who has not been infected with Covid or had a vaccine within the last six months to get another booster. The fifth jab will become widely available from February 20.

It was previously only available for severely immunocompromised Australians.

'From February 20, all adults who haven't had a booster or an infection in the past six months can go out and get a booster shot, to give them additional protection against severe illness from Covid,' health minister Mark Butler said.

'If you're 65 or over, or you're an adult at risk of severe Covid illness, and it's been six months since your last booster or infection, it's now time for a booster.'

Comment: Bad idea.

- Israeli survey shows Covid booster shots causing more injuries than previously thought

- Repeat COVID-19 vaccine booster shots trigger regulator warning about immune-system risks

- "Unexpected": MRNA vaccines increase risk of contracting COVID-19; each booster shot raises risk even more in study of 51,000 Cleveland Clinic workers

- Pfizer, Moderna reaping BILLIONS from COVID-19 injection 'booster' market

The announcement means Australians aged 18-29 will be eligible for a fourth vaccine but won't be offered to children unless they have health issues that put them at risk of severe illness.

Though the protein is a new discovery, there have been several studies that look at the body's relationship and response to Covid infection. Researchers from the University of Oxford found in October that some people will never get Covid thanks to their genes. They found that people who have a particular mutation produce a larger antibody response after getting vaccinated.

Around 30 to 40 per cent of people have the gene, known as HLA-DQB1*06. The boosted protection might be enough to block out infections entirely.

It may partly explain why some people never get the virus, even when family members come down with the virus.

Meanwhile, in December, another study found that Covid patients who suffered anosmia — a loss of smell — or agueisia — a loss of taste — were twice as likely to have antibodies long after an infection.

Promising pathway!?

If this is true then you don’t need any drugs as you have natural immunity.

But I think it’s bullshit, I think this is a way to trick people into receiving yet another dodgy medical product probably still containing mRNA and goodness knows what. They will say it’s developed from your natural responses produced by the body so you will be helping your body blah blah 😕

Any idiot going for a fifth is way beyond help so crack on. Maybe you can write up a speech for your Darwin Award for your friends to read at your funeral.

Fuck off with your novel bs medicine.