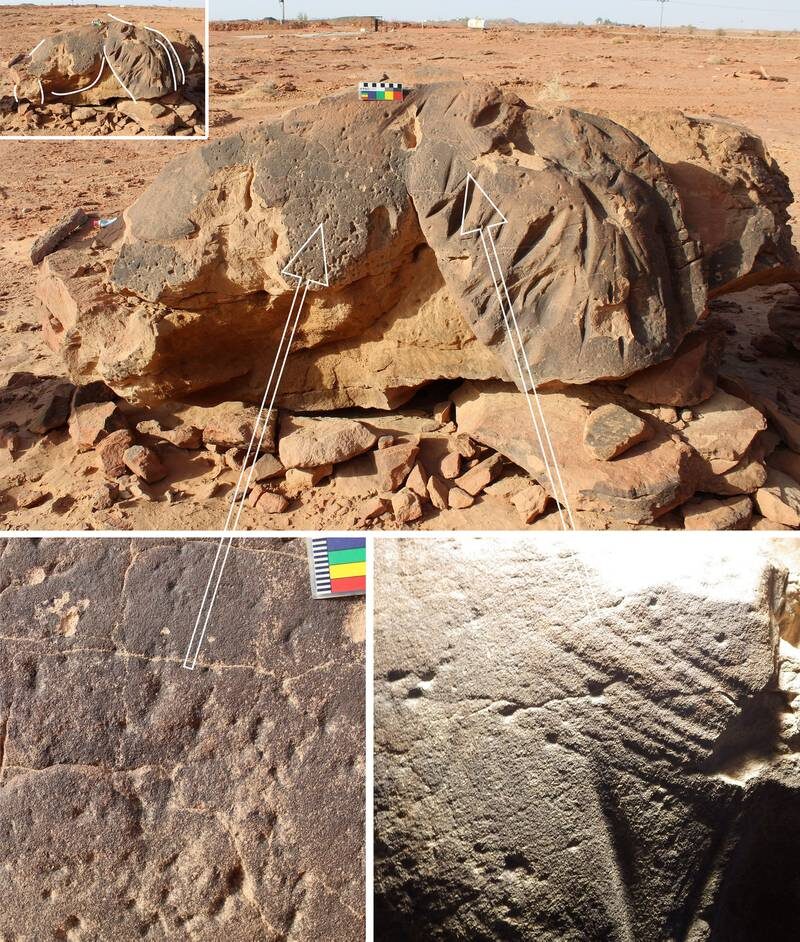

However, chemical analysis and the examination of tool marks helped to show that the carvings at the site were made in the sixth millennium BCE.

It means the remarkable life-size sandstone carvings of camels and other animals, including a donkey, are the world's oldest surviving large-scale reliefs.

"They are absolutely stunning and, bearing in mind we see them now in a heavily eroded state with many panels fallen, the original site must've been absolutely mind blowing," said Dr Maria Guagnin, from the department of archaeology at Germany's Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, the lead author of a new study on the late Stone Age carvings.

"There were life-sized camels and equids two or three layers on top of each other. It must have been an absolutely stunning site in the Neolithic."

Researchers heard about the site about five years ago and before the coronavirus pandemic, Dr Guagnin and other specialists made two visits of about 10 days each to examine the carvings.

The presence of camel reliefs at Petra in Jordan, produced by Nabataeans about 2,000 years ago, had suggested the Saudi carvings may be about two millennia old. However, a stone mason analysing the camel site carvings did not find evidence that metal tools had been used and there was no sign of pottery.

Weathering and erosion patterns, high-tech analysis involving fluorescence and luminescence and radiocarbon dating of remains also indicated an early origin.

"Every day the Neolithic was more likely [as the time when the carvings were made] until we realised it was absolutely a Neolithic site we were looking at," Dr Guagnin said.

Researchers also came from the Saudi Ministry of Culture, King Saud University and France's Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

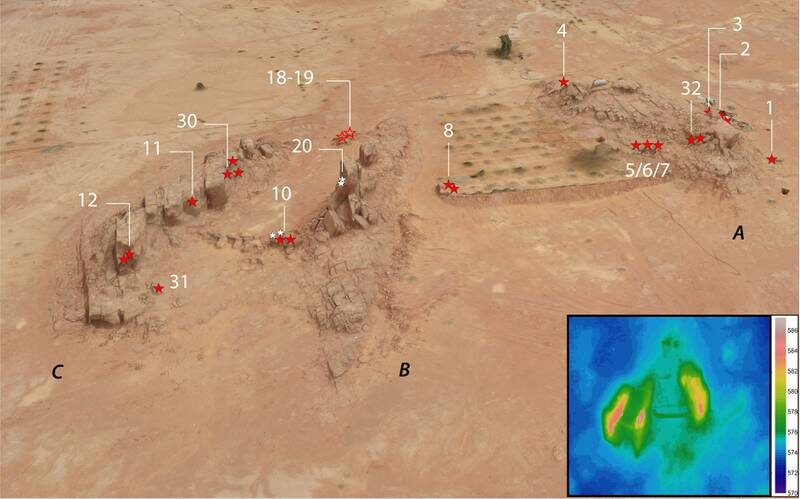

On three rock spurs there are 21 carvings, each thought to have taken about 10 to 15 days to complete, during which time the stone tools used would have been resharpened and replaced frequently.

The tools were made from a rock called chert, which came from at least 15 kilometres away, and a platform or rigging would have been needed to hold whoever was carrying out the carving.

The Max Planck Institute said the carvings were probably produced as part of a communal effort, perhaps involving an annual gathering.

"The weight gain and references to the mating season in the camel reliefs suggests that they may be symbolically connected to the yearly cycle of wet and dry seasons to which these biological changes are linked," the organisation said.

Most or all were carved by the late sixth millennium BC, but reconstructions of carving and weathering indicate that the site was used for generations and the panels re-engraved and re-shaped.

What exactly the site was used for, such as whether it was a place of worship, is unlikely to ever be known.

"Were they lighting fires underneath or feasting near them or just looking at them? One of the functions of rock art sites in general is not just in actual symbolism and belief that might be linked to the imagery. It's a way to mark space; this is the place we come to meet," Dr Guagnin said.

Attention now turns to preserving the site in the face of wind and moisture, and further studies of the sandstone are needed to determine what measures will be most suitable.

Researchers are also interested in whether there are other similar sites.

They have generated three-dimensional models of the site and these could be used to produce digital interactive models for the public.

With Saudi Arabia having begun to issue tourist visas in 2019, the camel site could become a major draw.

"The site itself is quite spectacular, seeing them in place," Dr Guagnin said. "If I was a tourist, I would want to go and see it."

Reader Comments

[Link]

[Link]

[Link]

Maybe look up Scarborough Fair (parsley sage (salvia divinorum) rosemary and thyme). Maybe add myristicin and scopolamine.

RC

I do and have always believed that there's some

violentwarrior strain in my genes which when I first learned about, caused me to think back to me attacking many bullies bigger and stronger than me even before I'd thought of such stuff.In this life (if that's how it works) it only took one time of some asshole with a firearm trying to kill me where I learned to never panic again in such fucked up situations.

I don't know if that's nature, nurture, soul, spirit, or whatnot, but it has been strange all of the violent events that have arisen around me and in which I've managed to always prevent others from being harmed/killed, and, as advised by those men's little brother/my uncle, I've still never killed anyone.

RC

Animanarchy Have you ever heard Neil Young, Pocohontas from Rust Never Sleeps? [Link]

That album came out when I was at U.F. and I still know it "note for note". GREAT SONG:

rc

By the time Neil Young's Harvest came out (72, I was 13) I already knew 'After the Gold Rush'. and by 'Comes A Time', I could play them all.

Do you play? I'd not be surprised.

RC

BTW, you might wish to read and comment here where G15b and yours truly have been chatting - I think that this kid has potential.*

Germany: Gas station employee killed over a face mask

A gas station worker in the town of Idar-Oberstein, Rhineland-Palatinate, lost his life after a dispute with a customer over COVID-19 measures, police said Monday. According to the police report,...*You know - you're one of those clueless youngsters also.

RC

BTW, what's a banger? Also, is that some primitive teepee that your avatar is or something else? Thanks.

RC

R.C.

[Link]