Learning how to skip stones across a lake or pond is a time-honored childhood tradition. The underlying physics of skipping stones could also be a useful model for landing aircraft or spacecraft on water, according to a recent paper published in the journal Physics of Fluids. Chinese physicists have built just such a model, and they used it to further clarify the key determining factors behind how many times a stone (or spacecraft) will bounce upon hitting the water.

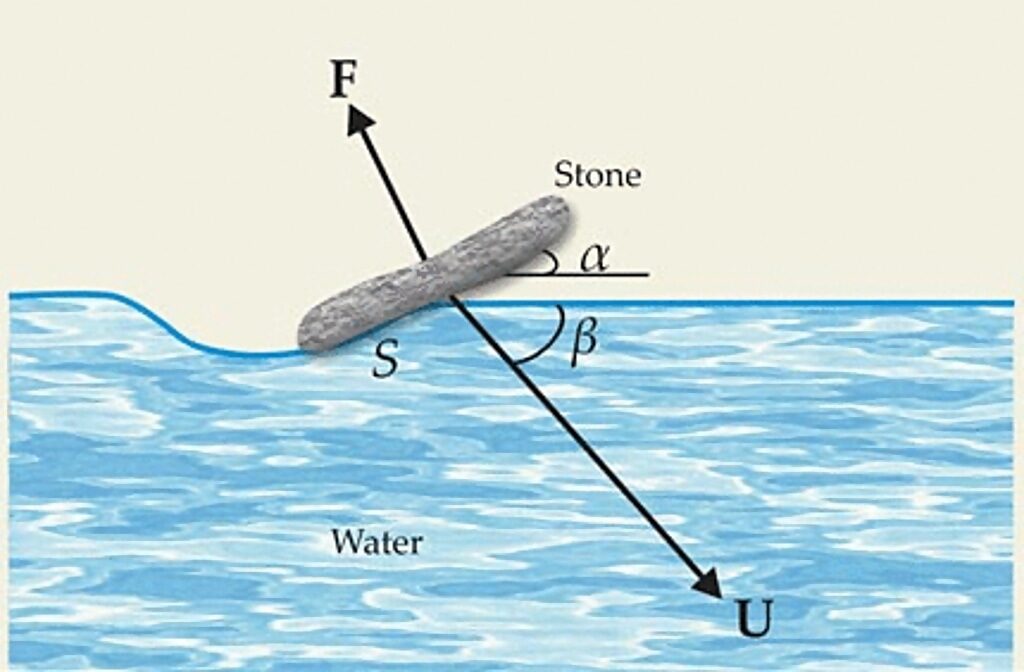

Skipping stones is just the sort of natural everyday phenomenon that would fascinate physicists, even though at first glance the basic concepts seem simple. It all comes down to spin, speed, shape of the stone, and angle. As the stone hits the water, the force of impact pushes some of the water down, so the stone, in turn, is forced upwards. If the stone is traveling fast enough to meet a minimum velocity threshold, the stone will bounce; if not, it will sink. A round, flat stone is best, simply because its surface area displaces more water as it skips.

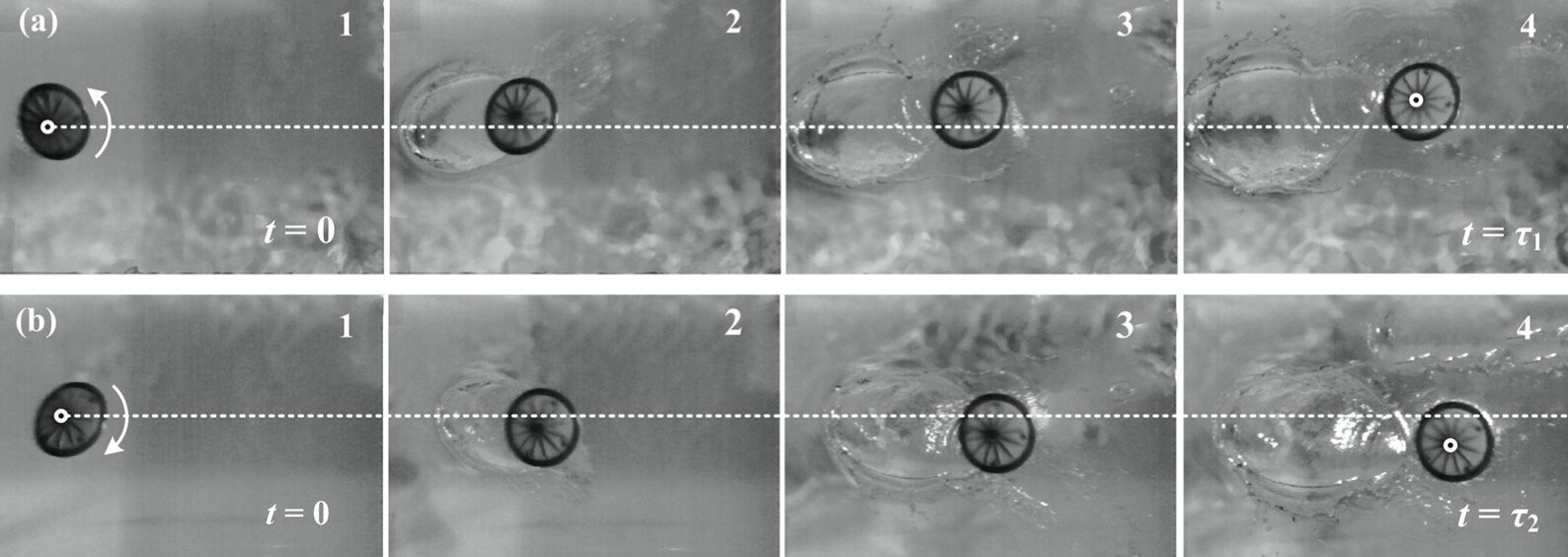

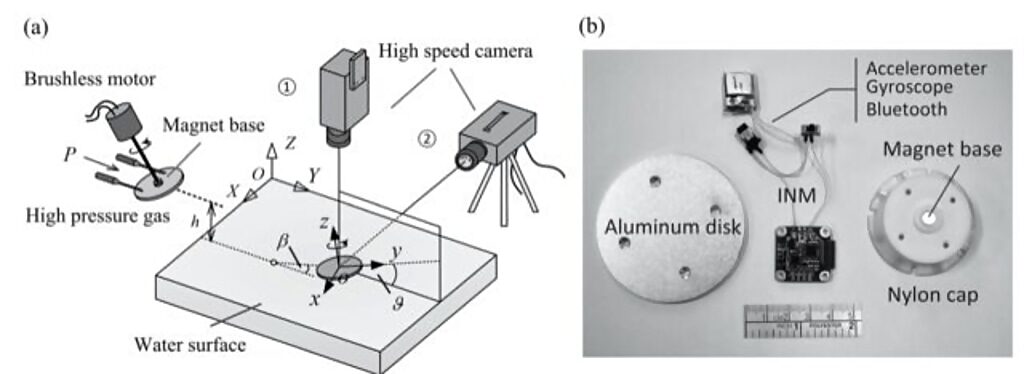

Experiments in 2004 by French physicists Lyderic Bocquet and Christophe Clanet demonstrated as much. They built a catapult device to toss aluminum disks at a tank of water and then recorded the splashes with high-speed video. They learned that the bouncing stone must be spinning at a minimal rate of rotation (at least once during its collision time) in order to be stable. In other words, a skipping stone relies on the gyroscopic effect, in which a body rotating around its own axis tends to maintain its own direction. (It's also what stops a spinning top from tipping over.) Experienced stone-skippers typically apply this rotation to the stone with a simple flick of the finger.

Bocquet and Clanet's experiments helped them determine how best to maximize the number of bounces. The obvious solution is to throw the stone as fast as possible, since the number of bounces is proportional to the throwing speed. But this must be balanced against being able to control the velocity and direction of the throw. Even with their catapult machine, the French physicists could only achieve about 20 bounces — significantly less than the current world record of 88 skips, set in 2013.

They gleaned further insight by examining what makes the stone stop skipping. It's not because the stone slows down; rather, its trajectory flattens over time. Bocquet and Clanet concluded that this occurs because of the angle at which the stone moves, relative to the water's surface. The stone displaces more water when it moves downward than when it's moving upward, so over time less and less transfer of momentum occurs, gradually reducing the lift. Eventually the stone no longer has sufficient energy to skip, and it will sink. Their experiments showed that the optimal angle between the plane of the stone and the water's surface is between 10 and 20 degrees.

In 2014, a Utah State University team experimented with bouncing elastic spheres across the surface of water, capturing the dynamics with a high-speed camera. The spheres are more elastic than rocks and thus deform into disks as they hit the water, taking on the ideal shape for a skipping stone. Because the plastic spheres can deform independent of the angle at which they hit the water and have a lower velocity threshold, achieving more bounces with them is much easier. In fact, anyone can achieve a good 20 skips with a plastic sphere after a mere 10 minutes of practice, according to USU physicist and co-author Tadd Truscott.

More directly relevant to the current paper, in 1929, Theodore von Karman conducted several experiments to determine the maximum pressure on seaplanes during water landings, and in 1932, Herbert Wagner showed that the takeoff and landing of a seaplane was essentially all about impacts and sliding on a liquid surface. "[Wagner] pointed out that the impact processes are predetermined uniquely by the initial motion of the liquid and the course of the movement of the body," the Chinese co-authors of this latest paper wrote in their introduction.

For their new research, the Chinese team focused on bouncing (skipping) and surfing, in which the disk or stone skims the surface and never bounces. The researchers came up with their own theoretical model of the phenomenon that incorporated not only the aforementioned gyroscopic effect, but also the Magnus effect. It's long been known that the movement of a baseball, for instance, creates a whirlpool of air around it. The raised seams churn the air around the ball, creating high-pressure zones in various locations (depending on the type of pitch) that can cause deviations in its trajectory. Something similar occurs with skipping stones.

The team found that the critical threshold for vertical acceleration is four times the acceleration due to gravity (4 g). The disk or stone will more likely surf if the vertical acceleration is a bit smaller (3.8 g), while the minimum threshold at which a stone has the potential to skip is 3.05 g.

The researchers also determined that it's the combination of the gyro effect and the Magnus effect — both produced as the spinning stone hits the fluid — that influences the deflection of its trajectory. The direction of that deflection, in turn, is controlled by the stone's direction of rotation (clockwise or counterclockwise). If the stone is rotating clockwise, the deflection bends to the right; if counterclockwise, the deflection bends to the left. The spinning helps stabilize the attack angle, thereby creating favorable conditions for the continuous bounce of the stone.

Thus, "Appropriate attack angles and horizontal velocities are the key factors in generating sufficient hydrodynamic forces to satisfy the conditions of bounce," the authors concluded. "Our results provide a new perspective to advance future studies in aerospace and marine engineering," added co-author Kung Zhao of the Beijing Electromechanical Engineering Institute. That perspective is most notable with regard to water landings of space flight re-entry vehicles and aircraft, as well as "hull slamming" (driving a ship's hull into the cross section of the hull of another vessel), and improving torpedo designs.

Reference: Jie Tang, Kun Zhao, et al., Trajectory and attitude study of a skipping stone, Physics of Fluids, 2021. DOI: 10.1063/5.0040158

Jennifer Ouellette is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Los Angeles.

"Water molecules on the surface are attracted more strongly to other water molecules than the air. This creates what is known as surface tension."

R.C.