Despite this unambiguous statement from the two most authoritative sources, most of the mainstream press — with the exception of The Economist — continue reporting that the U.S. economy is No. 1. So, what's going on?

Obviously, measuring the size of a nation's economy is more complicated than it might appear. In addition to collecting data, it requires selecting a proper yardstick. Traditionally, economists have used a metric called MER (market exchange rates) to calculate GDP. The U.S. economy is taken as the baseline — reflecting the fact that when this method was developed in the years after World War II, the U.S. accounted for almost half of global GDP. For other nations' economies, this method adds up all goods and services produced by their economy in their own currency and then converts that total into U.S. dollars at the current "market exchange rate." For 2020, the value of all goods and services produced in China is projected to be 102 trillion yuan. Converted to U.S. dollars at a market rate of 7 yuan to 1 dollar, China will have an MER GDP of $14.6 trillion versus the U.S. GDP of $20.8 trillion.

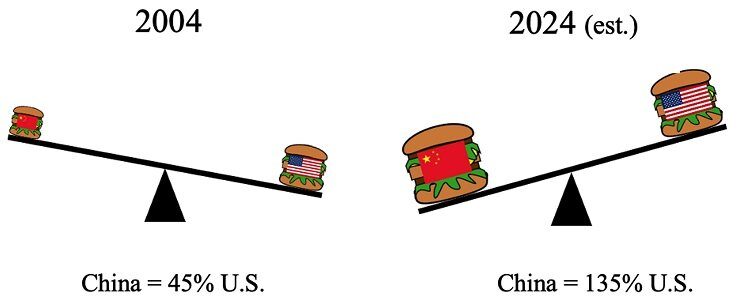

But this comparison assumes that 7 yuan buy the same amount of goods in China as $1 does in the U.S. And obviously, that's not the case. To make this point easier to understand, The Economist magazine created the "Big Mac Index" from which the graph at the top of this piece is derived. As this index shows, for 21 yuan, a Chinese consumer can buy an entire Big Mac in Beijing. If he converted those yuan at the current exchange rate, he would have $3, which will only buy half a Big Mac in the U.S. In other words, when buying most products from burgers and smartphones, to missiles and naval bases, the Chinese get almost twice as much bang for each buck.

Recognizing this reality, over the past decade, the CIA and the IMF have developed a more appropriate yardstick for comparing national economies, which is called PPP (purchasing power parity). As the IMF Report explains, PPP "eliminates differences in price levels between economies" and thus compares national economies in terms of how much each nation can buy with its own currency at the prices items sell for there. While MER answers how much Chinese would get at American prices, PPP answers how much Chinese do get at Chinese prices.

If the Chinese converted their yuan to dollars, bought Big Macs in the U.S., and took them home on the plane to China to consume them, comparing the Chinese and U.S. economies using the MER yardstick would be appropriate. But instead, they buy them at one of the 3300 McDonald's locations in their home country where they cost half what Americans pay.

Explaining its decision to switch from MER to PPP in its annual assessment of national economies — which is available online in the CIA Factbook — the CIA noted that "GDP at the official exchange rate [MER GDP] substantially understates the actual level of China's output vis-a-vis the rest of the world." Thus, in its view, PPP "provides the best available starting point for comparisons of economic strength and wellbeing between economies." The IMF adds further that "market rates are more volatile and using them can produce quite large swings in aggregate measures of growth even when growth rates in individual countries are stable."

In sum, while the yardstick most Americans are accustomed to still shows that the Chinese economy is one-third smaller than the U.S., when one recognizes the fact that $1 buys nearly twice as much in China than in the U.S., the Chinese economy today is one-sixth larger than the U.S. economy.

So what? If this were simply a contest for bragging rights, picking a measuring rod that allows Americans to feel better about ourselves has a certain logic. But in the real world, a nation's GDP is the substructure of its global power. Over the past generation, as China has created the largest economy in the world, it has displaced the U.S. as the largest trading partner of nearly every major nation (just last year adding Germany to that list). It has become the manufacturing workshop of the world, including for face masks and other protective equipment as we are now seeing in the coronavirus crisis. Thanks to double-digit growth in its defense budget, its military forces have steadily shifted the seesaw of power in potential regional conflicts, in particular over Taiwan. And this year, China will surpass the U.S. in R&D spending, leading the U.S. to a "tipping point in R&D" and future competitiveness.

For the U.S. to meet the China challenge, Americans must wake up to the ugly fact: China has already passed us in the race to be the No. 1 economy in the world. Moreover, in 2020, China will be the only major economy that records positive growth: the only economy that will be bigger at the end of the year than it was when the year began. The consequences for American security are not difficult to predict. Diverging economic growth will embolden an ever more assertive geopolitical player on the world stage.

Graham T. Allison is the Douglas Dillon Professor of Government at the Harvard Kennedy School. He is the former director of Harvard's Belfer Center and the author of Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap?

Food Shortages Hit China: There Is “not…enough fresh food to go around” [Link]