It's important to note that there are significant scientific controversies on both these questions. On diet and health, I can safely say that there is an enormous amount of legitimate scientific dispute surrounding the question of whether a plant-based diet is best for health and also whether minimizing red meat in the diet is healthy or even safe. The best, most rigorous (clinical trial) evidence supports the idea that red meat does not cause any kind of disease. There are also a number of analyses showing that diets low in animal foods are nutritionally deficient, thereby increasing the risk of many diseases and interfering with normal growth and brain development in children.

Evaluating the science on any subject requires convening a range of viewpoints so that scientific controversies can be fairly evaluated and discussed. Presumably The Lancet, an old and venerable journal, knows this. And yet an examination of the EAT-Lancet authors reveals that more than 80% of them (31 out of 37) espoused vegetarian views before joining the EAT-Lancet project.

This was clearly a highly biased group, and the outcome of their report was therefore inevitably a foregone conclusion. Convening a one-sided group on a topic cannot be expected to produce a balanced outcome. It would be like pretending to negotiate an agreement in Congress with only one party at the table. Like-minded people talking to themselves is not a scientific debate, and the product of these inbred conversations cannot be considered a scientific product.

Also, authors usually disclose their potential conflicts of interest when publishing. Clearly some of the conflicts listed below are "intellectual" rather than financial (and hence, not usually disclosed although at least one eminent scientist has well argued that they should be), but in many cases, the authors' potential conflicts involve their place of employment, in think tanks that promote vegetarian diets and/or meat reduction. If one's salary/livelihood depends upon supporting a certain point of view, this is arguably a very strong potential conflict of interest.

The leader on diet and health for EAT-Lancet was Harvard's Walter Willett, whose potential conflicts of interest are too extensive to list in this post. They include intellectual and financial conflicts, as well as affiliations with vegetarian groups, all of which are contained in a separate 8-page document here.

Comment: For a look at some of Willett's slimy connections, see: "Big Pasta" cooks up self-interested nutrition science.

None of these potential conflicts of interest are disclosed in the Lancet paper, which seems to be an extraordinary oversight.

Here are two emails for The Lancet if you would like to contribute your views on this issue: ombudsman@lancet.com, editorial@lancet.com

For Teicholz's complete list of the EAT-Lancet authors and their potential conflicts of interest, see original link.

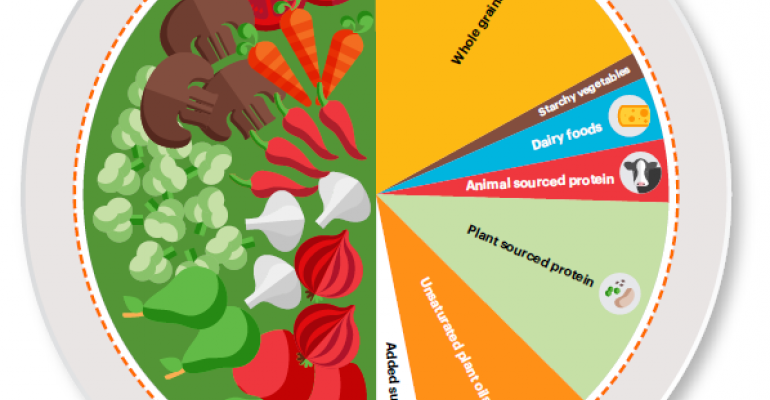

Comment: If you've seen the possibly hundreds of headlines in the past weeks proclaiming how everyone needs to cut meat from their diets to save themselves and the planet, that's because of the EAT-Lancet study, being promoted by every major news publication as established fact. Despite it's claims, however, it's not science. It's a propaganda piece brought to you by a cohort of biased vegans passing themselves off as "experts".

See also: