To demonstrate this, I shall first go back to an early partition plan - that of the British Royal Peel Commission of 1937, to gradually reach our present day.

The British Peel Commission partition plan

The British Royal Peel Commission was constructed in order to determine the origins of the great tensions between what they would regard as "Jews and Arabs", following the onset of the Great Arab Revolt by Arab Palestinians of 1936 (which lasted until 1939).

The Peel Commission report assessed that the "underlying causes of the disturbances of 1936" were:

(1) The desire of the Arabs for national independence;The Peel Commission's suggested solution was to separate the two populations. The 'Jewish state' would consist of the central coastal plain and the northern Galilee areas, the 'Arab state' would be from the West Bank down through to the furthest south, and in between, a corridor from Jaffa to Jerusalem would be under British Mandate auspices.

(2) their hatred and fear of the establishment of the Jewish National Home.

These two causes were the same as those of all the previous outbreaks and have always been inextricably linked together. Of several subsidiary factors, the more important were-

(1) the advance of Arab nationalism outside Palestine;

(2) the increased immigration of Jews since 1933;

(3) the opportunity enjoyed by the Jews for influencing public opinion in Britain;

(4) Arab distrust in the sincerity of the British Government;

(5) Arab alarm at the continued Jewish purchase of land;

(6) the general uncertainty as to the ultimate intentions of the Mandatory Power.

This solution would involve what it called "exchange of populations":

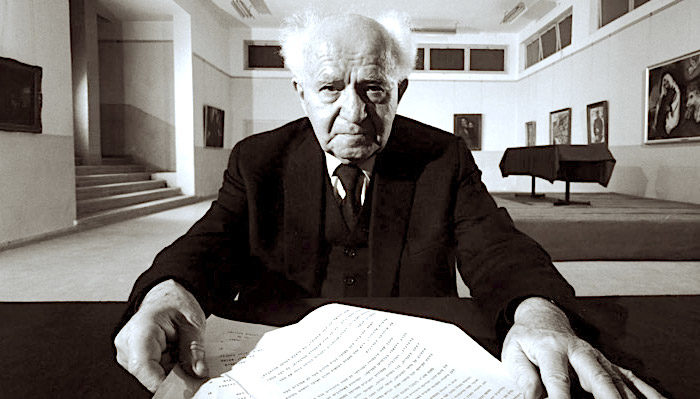

"If Partition is to be effective in promoting a final settlement it must mean more than drawing a frontier and establishing two States. Sooner or later there should be a transfer of land and, as far as possible, an exchange of population".What did exchange mean? The Peel Commission pointed out that there were about 225,000 Arabs alongside 400,000 Jews in the suggested Jewish state, and that minority- along with the 1250 Jews in the Arab state - created a problem. The existence of these minorities clearly constitutes the most serious hindrance to the smooth and successful operation of Partition. The Zionists understood "population exchange" as a euphemism for forced "transfer" in general, and they saw it as a welcomed opening and legitimation of their designs for ethnic cleansing so as to obtain a strong Jewish majority. David Ben-Gurion:

"In many parts of the country new settlement will not be possible without transferring the [Palestinian] Arab fellahin...it is important that this plan comes from the [British Peel] Commission and not from us...Jewish power, which grows steadily, will also increase our possibilities to carry out the transfer on a large scale. You must remember, that this system embodies an important humane and Zionist idea, to transfer parts of a people to their country and to settle empty lands. We believe that this action will also bring us closer to an agreement with the Arabs."Ben-Gurion's words confirm the utter centrality of "transfer" for the Zionist project. As Israeli historian Benny Morris put it:

"transfer was inevitable and inbuilt in Zionism - because it sought to transform a land which was 'Arab' into a Jewish state and a Jewish state could not have arisen without a major displacement of Arab population".Ben-Gurion, the Zionist leader who became the first prime minister of Israel, was in support of that partition - not as an end, but as a beginning. He wrote this to his son Amos in 1937:

"My assumption (which is why I am a fervent proponent of a state, even though it is now linked to partition) is that a Jewish state on only part of the land is not the end but the beginning. When we acquire one thousand or 10,000 dunams, we feel elated. It does not hurt our feelings that by this acquisition we are not in possession of the whole land. This is because this increase in possession is of consequence not only in itself, but because through it we increase our strength, and every increase in strength helps in the possession of the land as a whole. The establishment of a state, even if only on a portion of the land, is the maximal reinforcement of our strength at the present time and a powerful boost to our historical endeavors to liberate the entire country."And what, may we ask, is this "entire country"? The simple answer could be Mandate Palestine. But actually, Ben-Gurion had greater ambitions. Speaking in a Labor party meeting in 1937 in support of the Peel partition, he said:

"The acceptance of partition does not commit us to renounce Transjordan. One does not demand from anybody to give up his vision. We shall accept a state in the boundaries fixed today - but the boundaries of the Zionist aspirations are the concern of the Jewish people and no external factor will be able to limit them."This particular reference to Transjordan as a part of the coveted (some would say promised) land, put Ben-Gurion on par with the expansionist aims of the Jabotinskyite Revisionists to his right (they wanted a revision of the British Mandate to include Transjordan so that the Jewish State could cover both Palestine and Jordan. The Irgun emblem shows this as one territory).

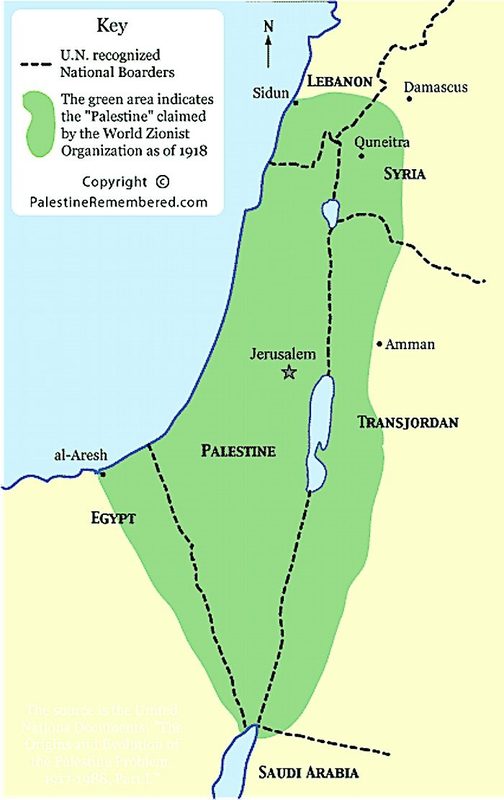

Actually, Ben-Gurion's visions of 'Eretz Israel' as he would regard it, and that he would covet, were yet bigger. In 1918 he described it:

"To the north, the Litani river [in southern Lebanon], to the northeast, the Wadi 'Owja, twenty miles south of Damascus; the southern border will be mobile and pushed into Sinai at least up to Wadi al-'Arish; and to the east, the Syrian Desert, including the furthest edge of Transjordan".A map of this vision was submitted by the World Zionist Organization in 1919 to the Paris Peace Conference in the wake of WW1.

The Peel Commission's partition plan was naturally met with vehement disagreement by the native Palestinians. Its bias was obvious, and only strengthened what the British had already noted as "Arab distrust in the sincerity of the British Government" as well as "the general uncertainty as to the ultimate intentions of the Mandatory Power". Eventually the plan was shelved. Yet the Zionists at the time were looking at the Peel partition plan with great interest, as mentioned. The "increase" and "reinforcement" of "strength" and the "powerful boost" that Ben-Gurion was writing about was not just a general political legitimation matter. The Peel partition plan had also entailed a population transfer, and was openly legitimizing it. It was using the precedence of the "exchange effected between the Greek and Turkish populations on the morrow of the Greco-Turkish War of 1922".

The Zionists were thus rather giddy at this point, because the most central, inevitable and inbuilt aspect of their colonization was now openly being suggested by a major world power.

Zionist leader and later 1st President Chaim Weizmann wrote to the British-Palestine High Commissioner in 1937:

"We shall spread in the whole country in the course of time ... this is only an arrangement for the next 25 to 30 years."Ben-Gurion would write in his diary in 1937:

"The compulsory transfer of the [Palestinian] Arabs from the valleys of the proposed Jewish state could give us something which we never had, even when we stood on our own during the days of the first and second Temples. . . We are given an opportunity which we never dared to dream of in our wildest imaginings. This is MORE than a state, government and sovereignty - this is national consolidation in a free homeland. With compulsory transfer we [would] have a vast area [for settlement] ... I support compulsory transfer. I don't see anything immoral in it."Ben-Gurion emphasized this position in 1938 once again:

"[I am] satisfied with part of the country, but on the basis of the assumption that after we build up a strong force following the establishment of the state - we will abolish the partition of the country and we will expand to the whole Land of Israel."The Zionists immediately acted on the Peel Commission notion of transfer, reading this as a principle green light for ethnic cleansing. They quickly established a Population Transfer Committee.

WW2, the White Paper and limiting Jewish immigration to Palestine

It would not be long before the world would be embroiled in another World War. Already in the 1937 Peel report, there was a recommendation to limit Jewish immigration, as a response to one of the mentioned causes of unrest:

"His Majesty's Government should lay down a political high level of Jewish immigration. This high level should be fixed for the next five years at 12,000 per annum. The High Commissioner should be given discretion to admit immigrants up to this maximum figure, but subject always to the economic absorptive capacity of the country" (chapter 10 in the report).Eventually the British Government decided to apply some of the recommendations of the Peel 1937 report, and it did so in 1939, on the eve of the war, with what is known as the White Paper. Concerning immigration, it limited this to 75,000 over the next five years:

"For each of the next five years a quota of 10,000 Jewish immigrants will be allowed on the understanding that a shortage one year may be added to the quotas for subsequent years, within the five year period, if economic absorptive capacity permits.Moreover, the White Paper went against the partition notion, and called for the establishment of a one independent Palestinian state within a period of ten years:

In addition, as a contribution towards the solution of the Jewish refugee problem, 25,000 refugees will be admitted as soon as the High Commissioner is satisfied that adequate provision for their maintenance is ensured, special consideration being given to refugee children and dependents."

"The independent State should be one in which Arabs and Jews share government in such a way as to ensure that the essential interests of each community are safeguarded."This put the Zionists in a very awkward position. Their endeavor was indeed to make Palestine a Jewish State, while the White Paper stated unequivocally:

"His Majesty's Government therefore now declare unequivocally that it is not part of their policy that Palestine should become a Jewish State."This was a major blow for the Zionists, in both political and practical terms. The duality of alliance that Zionists would now feel concerning the British, is epitomized in Ben Gurion's famous quote from 1939:

"We will fight the war as if there were no White Paper, and we will fight the White Paper as if there were no war."In 1942 Ben Gurion would gather thousands of Zionists at the Biltmore Hotel in New York, where the declaration therefrom included a complete rejection of the White Paper.

Although there were differing attitudes by various Zionist factions as to how this duality should play itself out throughout WW2, the end of the war also marked a moment of unity by all Zionist factions: in October 1945 they officially formed the Jewish Resistance Movement, wherein Ben Gurion's mainstream Haganah militias officially cooperated with the Revisionist militias (Irgun, Stern Gang), to attack British installations. The movement was officially dismantled in the wake of the King David Hotel bombing in 1946, where there was a disagreement about the timing of the attack, and the Haganah sought to distance itself from the Irgun and Lehi due to the somewhat unfortunate moral and political ramifications of the event in terms of public opinion. The main target of these militias was of course the eventual ethnic cleansing of Palestine, which would be achieved later, once it was clear that the British were disappearing as a colonial moderating force. They would later largely assist each other's main goal in the various raids of 1948, and the newly formed Israeli army would incorporate all factions into its ranks.

1947 partition plan

Come 1947, and Jews were now constituting about 1/3 of Palestine's population, owning close to 7% of the land. Nonetheless, the UN 'partition plan' awarded over 55% of the territory to them. This was of course internationally sanctioned colonialist expansionism by its very definition. The Palestinians naturally rejected it, and were right to do so, as Fathi Nemer excellently argues in his recent article on this site. The Zionists were of course elated once again by the partition plan, not because of the precise territory allocated (they were obviously not content with it, nor intended to stick to it), but because of the legitimacy afforded to the 'Jewish state'.

This plan, though not anchored in international law (it was not in the UN's mandate to create states), gave the Zionists a green light to continue the colonialist conquest of Palestine with full force. The campaign of ethnic cleansing began to take place well before Israel's declaration of statehood on May 14, 1948, by which time close to half of the Palestinian 1948 Nakba victims were already dispossessed, and over 200 Palestinian villages already destroyed. By early 1949, Israel had expanded beyond the UN partition plan lines, to 78% of historical Palestine.

Israel was never going to let those refugees back, because it was part of the whole point of creating a Jewish State.

Oslo accords

The 1993 and 1995 'Oslo accords' between Israel and the PLO came out of the famous 'peace process' which started in 1991 in Madrid, during which Prime Minister Itzhak Shamir coined the 'teaspoon policy': endless negotiating sessions at which countless teaspoons amounting to mountains of sugar would be stirred into oceans of tea and coffee, but no agreement would ever be reached. Yet lo and behold, under Yitzhak Rabin, an agreement was reached. Many were in the erroneous impression that this was already some kind of 'two state solution', but it was not. Rabin assured several times that it was not, and unequivocally called it "less than a state" as far as Palestine was concerned, when he spoke to the Knesset just a couple of months before he was murdered.

The Oslo accords were actually an 'interim' agreement, which indeed 'partitioned' what was left of Palestine (22%) into a complicated network of full Israeli control (area C) over what was effectively an archipelago of Palestinian Bantustans. Area C of the West Bank is over 60% of that territory, and surrounds these 'islands' from all directions. Indeed - less than a state.

And what would this 'interim' possibly result in? Well, that was subject to future negotiations which were to take place, with all critical issues, including territory, refugees, Jerusalem etc.

This would mean that at best, Palestinians would be given supposedly 'generous offers' such as that of Prime Minister Ehud Barak in 2000, which would still amount to Bantustans. Under this plan the Palestinian land share in the West Bank for the first 6 to 21 years would be about 77% (if all went well, and better than with Oslo). Barak would chide them for not being satisfied with that, and that there is hence "no one to talk to".

It has been somewhat of an orthodoxy in the West, that the Palestinian refugee return issue would simply be relegated to a "return" to the remaining bit of Palestine that would one day possibly be negotiated. Hence - the 'two state solution' as it would be called, would represent a legitimation of the ethnic cleansing of Palestine, preserving the Zionist mission of 'Jewish state' which could not exist without ethnic cleansing.

It is worth noting in this respect, that even in the 'Clinton parameters' of late 2000, which went much further than Barak's 'generous offer' of summer 2000 (Camp David), the refugee issue had to be taken away from Israel: both parties had to agree that refugees would not return to Israel, but to what was left of Palestine (or resettled elsewhere), and that this would satisfy UN Resolution 194 of December 1948 calling for their return. Following the failed negotiations of these parameters in January 2001 (Taba), the parties declared that "they have never been so close to an accord".

A private note written by Barak to his Foreign Minister Shlomo Ben-Ami on the eve of the Taba negotiations, reveals the absolutely intransigent Israeli attitude concerning refugees:

"Shlomo shalom(This note was passed on to Avi Shlaim and is cited in his updated edition of The Iron Wall).

- Enormous readiness for a painful settlement but not a humiliating one. (the right of return).

- Vital to preserve hope ...but with realism - there is no agreement because we insist on what is vital for Israel (no right of return, appropriate settlement blocs, Jerusalem and the holy places and security arrangements)".

Notice, how the refugee right of return is considered "humiliating" by Barak.

Barak eventually suspended the talks, in order to attend to the upcoming elections, in which he was expected to lose to Sharon, and did, by a landslide.

"Disengagement" from Gaza

If Zionists accept 'partition' in historical Palestine, this is to be considered a temporary matter as we have seen, and a move that offers some future prospect of expansion. Hence, Sharon's famous 2005 'disengagement' from Gaza, was a move designed to strengthen, not weaken, Israeli expansionism. Sharon's senior adviser Dov Weissglass expressed this ahead of the 'disengagement':

"The significance of the disengagement plan is the freezing of the peace process. And when you freeze that process, you prevent the establishment of a Palestinian state, and you prevent a discussion on the refugees, the borders and Jerusalem. Effectively, this whole package called the Palestinian state, with all that it entails, has been removed indefinitely from our agenda. And all this with authority and permission. All with a presidential blessing and the ratification of both houses of Congress. [...] That is exactly what happened. You know, the term 'peace process' is a bundle of concepts and commitments. The peace process is the establishment of a Palestinian state with all the security risks that entails. The peace process is the evacuation of settlements, it's the return of refugees, it's the partition of Jerusalem. And all that has now been frozen.... what I effectively agreed to with the Americans was that part of the settlements would not be dealt with at all, and the rest will not be dealt with until the Palestinians turn into Finns. That is the significance of what we did."It is internationally and widely understood that Israel never really 'disengaged' from Gaza. It merely took some 8,000 settlers out, threw the key away, and kept controlling Gaza, which has now become an uninhabitable concentration camp, subject to seasonal massacre campaigns.

As Weissglass noted, Israel got points for its settler-expansionism in the West Bank, and the Oslo area C has become a major arena for accelerated ethnic cleansing, with various future plans for annexation coming also from government officials.

This is what 'partition' means for Israel. It never meant a 'two state solution' as we would generally understand it. Israel has never accepted the existence of an actual Palestinian state on any part of historical Palestine, only some form of 'autonomy' in "less than a state" as Rabin said, or in a "state minus" as Netanyahu said.

It is natural that many people perceive 'partition' as a kind of compromise: both 'sides' get a part of the cake, as it were. But this is not a correct appraisal, when the balance of power is as it is. In this state of affairs, any 'compromise' that Israel accepts is only a strengthening of its power to take more. Just as Ben-Gurion had written to his son in 1937:

"This is because this increase in possession is of consequence not only in itself, but because through it we increase our strength, and every increase in strength helps in the possession of the land as a whole".The question is, whether we want to let Palestinians be subject to the schemes of Zionists, David Ben-Gurion, Dov Weissglass, et al, because that would mean that they would not get their rights until they all turn into Finns. In other words, when hell freezes over.

About the Author:

Jonathan Ofir is an Israeli musician, conductor and blogger/writer based in Denmark.

Reader Comments

Caligula in charge of the EU? Imhotep in charge of Egypt?

Setting up Israel IN Palestine was utter madness. what a way to treat your cousins.

Cousins? yes....we all are. get over it.