The Reagan Commission on Organized Crime spent much of 1984 attacking Deak's global foreign exchange firm, Deak-Perera. By the end of the year, Deak was forced to appear before the commission in a testy public interrogation; his financial empire collapsed within days.

A year later, in 1985, Deak was assassinated in his Wall Street high-rise by a paranoid-schizophrenic bag lady from Seattle, who'd been hired for the job by Latin American mobsters, according to a private internal investigation led by former FBI detectives. The assassin, Lois Lang (pictured above), had previously spent several murky years in the underbelly of Silicon Valley, where she fell under the care of a famous Stanford Research Institute psychiatrist, Frederick Melges - an expert on dosing his subjects with drugs and hypnosis to induce "artificial" dissociative states. Perhaps not surprisingly, Dr. Melges was up to his eyeballs in secret CIA behavior modification programs that were going on at Stanford until they were exposed in Congressional hearings in 1977. [For more on this stranger-than-fiction story, read "James Bond and the Killer Bag Lady" co-authored with Alexander Zaitchik.]

Nicholas Deak's end came fast. Exactly thirty years ago, in 1984, his global financial empire, Deak-Perera, was accused by the Reagan Administration of laundering hundreds of millions of dollars of Colombian drug cartel cash.

Nicholas Deak should've been the least likely target for a Reagan Administration takedown over cocaine money laundering, and not only because the same Reagan Administration was busy aiding and abetting the CIA's mercenary army, the Contras, as they moved cocaine into the US, and illegal weapons into their Honduras bases. What made targeting Deak all the stranger was that one of Deak's closest longtime friends, William Casey, was head of Reagan's CIA at that time. And as Gary Webb's reporting (and Robert Parry's exposés before and after Webb) have shown, Casey's CIA was at that very same time aiding and protecting the Contras' cocaine-running operation.

Deak's downfall was covered in the New York Times by a young greenhorn Ivy League grad named Nicholas Kristof, a budding serial dupe who, unsurprisingly, failed to connect the giant dots in front of his face about Deak's deep ties to the CIA, and his close personal relationship with the Agency's director, Bill Casey.

Kristof's December 1984 article, "Collapse of Deak & Company," begins:

Founded in 1939 by a Hungarian immigrant, Nicholas L. Deak, the company grew into prominence by making markets in currencies no one else would touch and in later years, by aggressively promoting private investment in gold. Today, it is the largest nonbank foreign exchange and precious metals operation in the United States.In the world of foreign exchange and precious metals, no name glitters like Deak-Perera.

..At the heart of the collapse, according to the Deak family, are allegations in a report by the President's Commission on Organized Crime about the laundering of money, so that drug traffickers could secretly repatriate profits to Latin America. Kristof did enough of his archive searching to uncover Deak's role in some spectacularly shady intelligence operations, but somehow managed to miss Deak's own intelligence links - including Deak-Perera's central role in the Lockheed Bribery Scandal, the "Watergate of Corporate America," under which the CIA funneled millions of bribe dollars to a Japanese war criminal-turned-Yakuza don, who used the funds to influence Japan's ruling party. Deak-Perera moved the CIA's funds; Lockheed reps and a Spanish-born priest in Macao carried the cash. Here, however, Kristof leaves out the CIA's role, so that it all appears, in Kristof's limited grasp, to reflect "the peculiar world of high finance":

[T]he report of the President's Commission, and testimony before it, offer some glimpses into a peculiar world of high finance.- From 1969 to 1975, Deak & Company was the conduit used by the Lockheed Corporation to transfer money intended by Lockheed to bribe Japanese officials. That bribery scandal resulted a year ago in the criminal conviction of a former Prime Minister, Kakuei Tanaka. In 15 deliveries, Deak & Company moved $8.3 million to Hong Kong, where a Spanish-born priest representing Lockheed took the cash and carried it to Japan in a flight bag or in cardboard boxes labeled ''oranges.'' "Lockheed Corporation came in and asked us to make a payment," Leslie Deak explained. "We made a payment. The fact that the money was used later for bribes is Lockheed's shame, not ours."

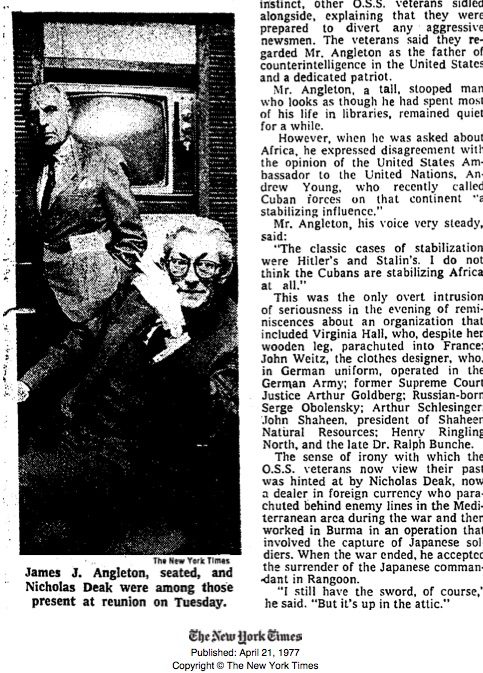

- The most serious charges involve the "laundering" of tens of millions of dollars garnered by cocaine traffikers. David Williams, an investigator for the commission, said in hearings in March that the "Grandma Mafia" - a well-known cocaine ring that involved many middle-aged or elderly women - deposited $7.6 million. The money was later transferred to Miami, Panama and Colombia, and Mr. Williams quoted a leader of the ring as doubting that her contact in the company could have been so naive as not to have known the origin or the money. Had Kristof checked his own paper's archives a little more thoroughly, he would've spotted a 1977 New York Times article on the powerful Veterans of the OSS organization - whose president through those years was Nicholas Deak, whom the Times photographed in a private room beside his colleague and friend, James Jesus Angleton, the paranoid founder of the CIA's counterintelligence division.

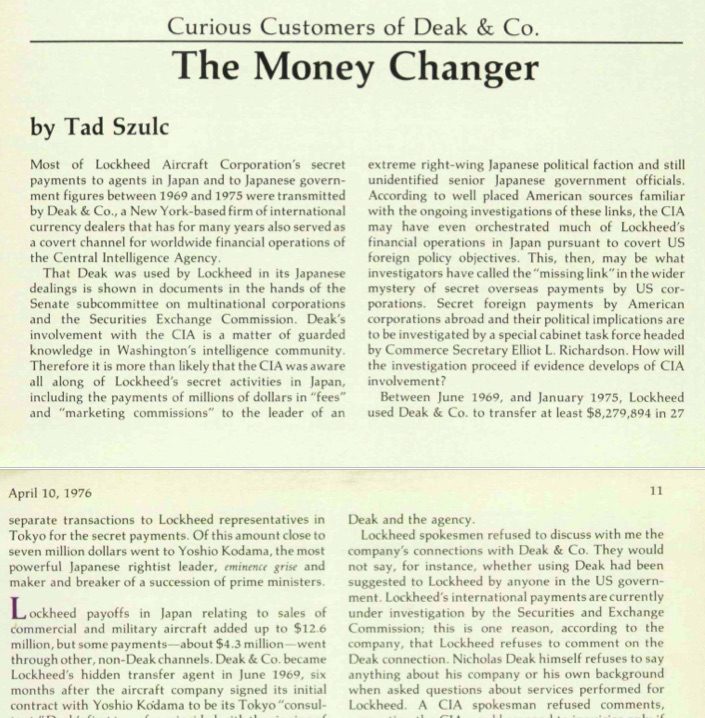

Had Kristof dug a little deeper, he would've come across his former New York Times colleague Tad Sculz's blockbuster exposé in the New Republic's April 10, 1976 issue, reporting leaks from the Church Committee on Deak-Perera's role as the CIA's money mover:

Most of Lockheed Aircraft Corporation's secret payments to agents in Japan and to Japanese government figures between 1969 and 1975 were transmitted by Deak & Co., a New York-based firm of international currency dealers that has for many years also served as a covert channel for worldwide financial operations of the Central Intelligence Agency.Deak's involvement with the CIA is a matter of guarded knowledge in Washington's intelligence community.

Sculz was the anti-Kristof: one of the great investigative reports of the Cold War, he had been targeted by the CIA as "anti-agency" and "under suspicion as a hostile foreign agent" - used his Senate sources to shine light into Deak's essential finance role in CIA covert operations:

Having built his company into one of the leading United States foreign-currency dealer firms, Deak is said to have performed various covert services for the CIA in the last 25 years....Deak is said, for example, to have handled CIA funds in 1953 when the agency overthrew Iran's Premier Mohammed Mossadeq and restored the Shah to the throne. In that instance, the money went through Zurich and a Deak correspondent office in Beirut. During the Vietnam war, Deak & Co. allegedly moved CIA funds through its Hong Kong office for conversion into piastres in Saigon on the unofficial market. Deak officials in Hong Kong and Macao helped the CIA investigate Far East gold smuggling in the mid-1950s. It has also been suggested that Deak & Co.'s Hong Kong office may have 'laundered,' with the CIA's knowledge, illegal contributions to the Nixon reelection campaign in 1972, although it is unknown whether Deak & Co. was aware of the precise nature of that operation. The Lockheed Bribery Scandal, with Deak and the CIA at its center, led to the passage of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, the first ever law criminalizing bribery of foreign officials.

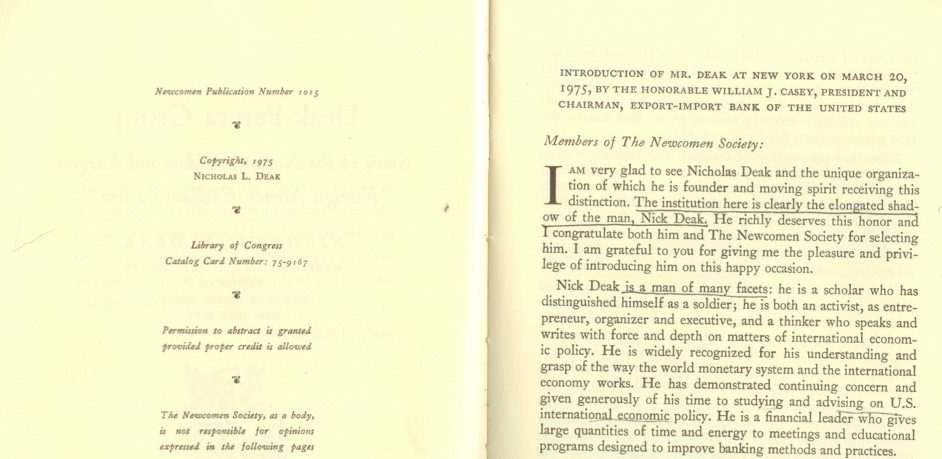

Around the same time that was going on, in 1975, Bill Casey gave a speech at a banquet honoring Deak. They'd bonded as spies in World War Two, and carried on throughout the Cold War, always keeping close to their intelligence comrades working inside the Agency. "It is a privilege to share this moment in the remarkable career of such an old and good friend and companion as Nick Deak," Casey said:

Having had the privilege of seeing Nick Deak in action and being with him in some of his endeavors, I claim to speak about him with authority. During World War II, both of us served in the Office of Strategic Services under the Great and legendary 'Wild Bill' Donovan. We served in different parts of the world-I in Western Europe, Nick in Southern Europe and Southeast Asia-but I can attest to the high reputation for courage, boldness and reliability which he acquired in the OSS and for the esteem in which Bill Donovan held him.Having from time to time counseled Nick Deak as lawyer and friend, I have had the opportunity to witness, and to some degree to understand, the remarkable way in which he developed the Deak-Perera Group.

Casey described how Deak, a Hungarian aristocrat from a prominent banking family, emigrated in 1939 to the US, rose up the elite wartime spy agency, and helped the US transition into a global empire with his unique grasp of global finance:

As soon as World War II began, he joined the U.S. Army. His knowledge of Europe and his linguistic abilities brought him quickly to the Office of Strategic Services. He was first assigned to our Middle East Headquarters at Cairo and was given responsibility in the Eastern Mediterranean with particular emphasis on the Turkish border, Cyprus and Crete. After the landings in North Africa, Sicily and Italy in the Western Mediterranean, our interests in the Eastern Mediterranean diminished, and Captain Deak was assigned to intelligence work in Burma, Thailand and Malaya.In August, 1945, Nicholas L. Deak, in charge of an OSS unit, at the airport in Rangoon, Burma, accepted on behalf of the United States, the sword of surrender of the Commanding General of the Japanese forces in Burma. He wound up commanding an OSS unit in Indochina and was sent, at the end of his military duties, to Shanghai in China, being discharged with the rank of Major. For another year, he continued his intelligence and political duties in Asia and Washington with the Department of State.

Returning to New York in 1946, he resumed the foreign exchange business he had started in 1939. The Deak-Perera Group was on its way.

The tightly integrated, interdependent world economy which we know today was then just beginning to evolve. Businessmen were encountering obstacles and frustrations flowing from the foreign exchange restrictions which then prevailed. To function in foreign trade and investments, they needed sophisticated knowledgeable advice. Deak and Co., Inc. remedied that problem in America. At the time of his speech honoring Deak, Bill Casey was serving as the head of the Export-Import Bank, having earlier served as chairman the SEC under Nixon. In 1984, as head of the CIA, Bill Casey was the dark face of Reagan's Central America policies: The dirty wars in Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador that left tens of thousands dead; the illegal mining of Nicaragua's harbors; the illegal Iran-Contra covert operations to fund the Contra mercenary army by selling arms to Ayatollah Khomeini; and the darkest operation of all, the CIA's involvement-passive or otherwise-in helping their Contra mercenaries run cocaine into America's cities to finance their death squads, an operation that eventually put the Contra drug runners in business with "Freeway" Rick Ross, the crack cocaine kingpin of the 1980s.

And so in 1984, the Reagan Commission on Organized Crime spent most of the year trying to compel Nick Deak to testify before the committee, led by a federal prosecutor and West Point grad named Jim Harmon. Members on the commission included segregationist Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond, and the powerful first cousin of Vice President George Herbert Walker Bush - John M. Walker Jr., assistant secretary of the Treasury Department in charge of enforcement and financial crimes. (Vice President George H W Bush also led a number of powerful Reagan task forces - on terrorism, drugs, and drug money laundering in South Florida, among others.)

I interviewed Harmon in 2010 about his commission's takedown of Deak. In our talk, he was very friendly and forthcoming, with no hint of malice, and no residual memory of hostility in the proceedings.

"Nicholas Deak was quite a guy-parachuting into Romania, accepting Japan's surrender in Burma," Harmon told me by phone. "Before our investigations, money laundering wasn't illegal because there were no laws against it. We needed to learn the ins and outs first, and that's why we called in Deak. We called others too-EF Hutton, Steve Wynn-it's thanks to what we learned from them that we were able to devise the world's first anti-money laundering."

And yet in early 1984, after Deak publicly refused to testify in Washington alongside mob informant Jimmy "The Weasel" Fratianno, Harmon lashed out before reporters: "Mr. Deak will be asked to explain how over $100 million was laundered through his company and further into various criminal schemes."

Finally, at the end of November 1984, the commission used a subpeona to force Deak to testify in Washington, appearing just before a hooded Colombian witness gave testimony about how he laundered drug funds through Deak.

The back-and-forth between Harmon and Deak, available on transcripts of the hearings, reveal a bristly and menacing Nicholas Deak, whose sardonic answers have an almost "you've got to be fucking kidding me" quality to them. Given everything a money man like Deak knew about the history of CIA covert operations, which invariably involved mixing with the underworld-as well as what Deak knew about his old friend Casey's operations in Latin America, at the center of which were cocaine and arms shipments - Deak's sarcasm comes off more like a condemned spy trying to remain dignified during his own kangaroo trial and impending execution:

- HARMON: Of the possibly billions of dollars [in Deak-Perera turnover], you recognize as you sit here today that there could be substantial amounts of money passing through your companies, put there by cocaine traffickers or heroin traffickers: is that right, sir?

- DEAK: I am not aware of it.

- HARMON: It could be though today?

- DEAK: Anything could be.

- HARMON: Well, you know, sir, as you sit here today that in the Orozco case to which you refer that one money launderer passed through $97 million through one account at Deak-Perera: isn't that right, sir?

- DEAK: That is what I understand has happened, yes.

- HARMON: Well, what did you do, Mr. Deak, after you found out that one money launderer had put $97 million through Deak-Perera to make sure that that wouldn't happen again?

- DEAK: I would recommend to the Government to be more alert when we are filing the reports.

* * * *And these exchanges, which read like something straight out of LeCarre, all the more so if you could hear Deak's famous Transylvanian accent:

- HARMON: Are you aware in any way, Mr. Deak, of the serious consequences of the use of cocaine?

- DEAK: That is not my field. I'm sorry. I cannot answer that question.

- HARMON: If you knew, Mr. Deak, things that the Commission has heard here during the last couple of days that cocaine is addictive, and that cocaine wreaks havoc with people's lives, do you think you might change Deak's policy to ...prevent narcotics traffickers from putting money through your companies?

- DEAK: Mr. Harmon, what policy do you refer to?

- HARMON: You have made no effort, have you, Mr. Deak, to examine past transactions by narcotics traffickers to see whether or not there should be a change in company policy; isn't that what you've said, sir?

- DEAK: I think that we - you asked it repeatedly. The policy is that we accept deposits if we are authorized to accept deposits. The policy is that if the deposit is suspicious, that the teller has to report it, and it is up to the authorities then from that moment on to investigate.

- COMMISSIONER SKINNER: Is it your -

- DEAK: We are not an investigative body. That is you, gentlemen, that should do that.

But what Deak knew, and what Kristof and the rest of the press corps should've known, was that Commissioner Skinner wasn't being "fair" - and that fairness never had anything to do with the business of covert empire management.* * * *

- COMMISSIONER SKINNER: Our concern is as being one of the major money processing firms in the world, is it not incumbent upon you, your company, as a matter of policy, to reject, summarily reject at the window, deposits of huge cash where suspicious factors are present which lead you to believe that the money being processed by your institution may result from illegal activities?

- DEAK: Mr. Chairman, first of all, you flatter me when you say that we are one of the major money processing institutions in the world. We are a fraction by size compared to the major banks, a fraction of a fraction.

- SKINNER: [T]here are other major financial institutions, as a matter of policy, I should tell you, that have advised us that they do routinely reject account balances and clients from their institutions unless they verify certain circumstances, and I think the Commission is trying to understand why your organization does not take a similar policy.

- DEAK: I am not aware of that, but if that is, indeed, the case, and obviously it is the case because you, Mr. Chairman, say so, my guess is that there are very few major institutions following this policy, and if they do follow, well, more credit to them.

- SKINNER: Well, Mr. Harmon, any more questions?

- HARMON: Yes. I'd like to just point out one thing. Mr. Deak has referred in some ways to our interim report. I would point out finally, Mr. Chairman, that several banks used by Orozco literally threw him out on his ear once they suspected that he was using those banks for criminal purposes. Those include the Chase Manhattan Bank, Marine Midland, Irving Trust Company, and Credit Suisse. Do you have any explanation, following up on what the Chairman has asked you, why those several banks found it in their interest and in the interest to their community to throw Orozco out?

- DEAK: Mr. Harmon, I think that we were more useful than those banks which you suggest because those banks refused. We reported it to the Federal authorities. Isn't that better? If we would have refused him also, you would have never learned about it.

A year later, Deak was murdered, along with his receptionist, by the unlikeliest assassin imaginable - a homeless paranoid-schizophrenic from Seattle by way of Mountain View, Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, and the forgotten goings-on at the Stanford Research Institute.

Gary Webb was hardly the first journalist to pull up the floorboards and shine light onto the dark workings of empire. It's not a pretty sight, and despite all the official Enlightenment cant about transparency and human improvement, there are a lot of people in this country who don't want to know. Quite possibly a majority, even a supermajority - that was the lesson of the Reagan Revolution, it's a lesson brilliantly retold in Rick Perlstein's new book "Invisible Bridge," and until someone can make a strong rational case - not a religious case based on liberal morality or Enlightenment cant - why all the non-journalists and non-liberal arts grads in this country's lives are necessarily improved by learning every horrible shitty thing this country does - and that list is long, like reading all the names of the war dead - then we may as well admit that Gary Webb was driven to suicide so that one day, we might safely troll each other on Twitter, the perfect insta-medium to nurture our selective amnesia, without ever having to put much on the line.

Comment: The Truth Perspective: Interview with Douglas Valentine: The CIA As Organized Crime