© Dirk Bakker, Allen Memorial Art Museum.Usonian House, Oberlin, Ohio

Frank Lloyd Wright once boasted that he didn't design his buildings to last for more than a century. It's not something you hear from many architects. But that doesn't mean Wright was being humble. Indeed, there's a hefty element of hubris to this admission. With Wright, you always get the sense that the conception, as realized in his beautiful drawings, was more important than the structures themselves.

Then again it was true. While most of Wright's homes have stood up pretty well over the years, a few of his better designs began to crack and crumble soon after they were erected. Usually, this was a result of Wright trying to build on the cheap, often by using local sand as a source for the reinforced concrete that became a signature of his later buildings, such as La Miniatura, the house in the Hollywood Hills that looks like a compact Mayan temple. (Of course, it took the giant temples of Tikal 600 years to acquire the characteristics of a ruin and La Miniatura only a decade.)

It's also an idea that Wright swiped from the Japanese, whose traditional houses were temporal structures, built to last for only for a few years. Characteristically, Wright didn't credit them, though he did admit to a fondness for Japanese art, especially the woodblock prints of Hiroshige and Hokusai.

More fundamentally, Wright held to the theory that a house should be designed to reflect the specific needs and personality of its occupants. It was a tenet of his notion of "organic architecture". According to this mode of thinking, there was no reason for a building to outlive its owners. Houses should be constructed to function well for forty years or so and then torn down to make way for new structures for new owners.

This was a way to keep architecture moving forward, to keep on, as Wright said, "breaking out of the box". It was also an attitude that may have grown out of some his personal peeves. Wright hated the English and described most of their architecture (Edwin Lutyens, the Walter Scott of English architecture - was a notable exception) as monuments to British imperialism. He so thoroughly despised the old Victorians that loomed near his house in Oak Park, Illinois that he built a wall around his home and studio and designed that house's curious windows so that he wouldn't have to look at the hulking outlines of the older structures.

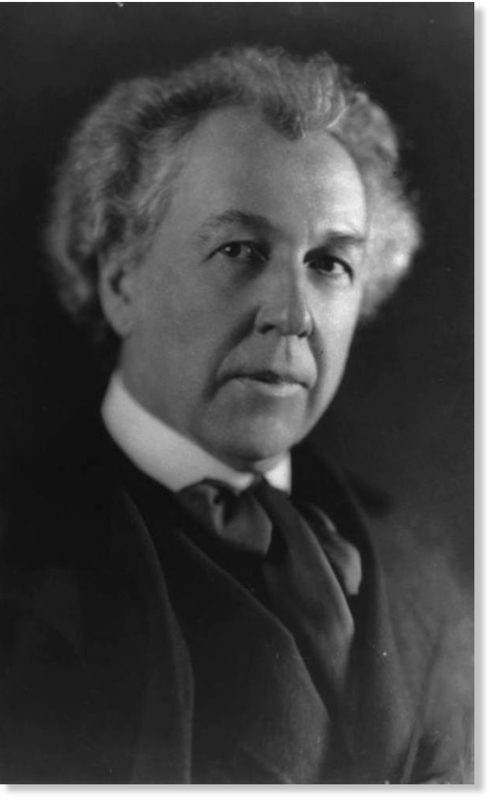

© Library of Congress.Wright in 1926

Even so, Wright spent most of his first 20 years as an architect drafting up homes as sturdy and immutable as anything conjured up by Antonio Palladio or Christopher Wren. The justly famous prairie designs of the early 1900s weren't houses so much as striking horizontal mansions for millionaires, equipped with parlors, music rooms and discreetly hidden quarters for servants.

These days, of course, the super-rich couldn't care less about Wright's houses, except as they are portrayed in coffee table books, and they cringe at the prospect of actually living in them. It's mega-square footage and techno-wiring that matters now. Wright's houses (even the big ones such as Hollyhock House and the Frank Thomas House) are too small to contain the accumulated trappings of today's millionaires. And they are downright impossible to re-decorate, intentionally so, since Wright didn't trust anyone's taste over his own. Most of his houses didn't even have closets, where would all the shoes go? Plus people (often of the most noisome disposition) are always showing up at the door wanting a peek at the structure. Much better to buy up the land, then hold the house for ransom with a wrecking ball and wait for a buy out.

That's exactly what happened to the Gordon house, the only structure Wright designed for construction in Oregon. Wright drafted plans for the house in 1957 and it was constructed on a bend in the Willamette River near Wilsonville in 1963, four years after his death, for Conrad and Evelyn Gordon. After the Gordons died, the house fell into disrepair following the predictable familial spat over whether or not to subdivide the homestead.

In 1999, the property was bought by David Smith for $1.1 million dollars. Smith had no plans to live in the house, a t-shaped two-storied structure made of cinderblocks and Oregon cedar. Instead, he announced his intention to bulldoze it and build on its grave a sprawling mansion to rival the other executive monstrosities that line the Willamette River these days. Apparently, Smith and his wife Carey had no idea who Wright was and didn't much give a damn after they found out. They had good reason to be smug. Within the past couple of years, the Portland area (supposedly home to the most progressive zoning and historical preservation laws on the continent) has seen houses by three of its most notable local architects, John Yeon, Walter Gordon and Pietro Belluschi destroyed, with barely a squawk of protest.

But Yeon - Oregon's version of California's Bernard Maybeck, doesn't' enjoy Wright's cult following and once word leaked about the Smith's plans, an international crusade was launched to save the structure. It is a testament to the power of the Wright name and the influence of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy that not one of the remaining 350 structures designed by Wright has been demolished in the last 12 years.

The Smiths offered to give the house to anyone who'd take it (they weren't keen to pay for the demolition), as long as they removed it within 105 days or they'd flatten it themselves. Ultimately the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy and the Oregon Chapter of the Institute of American Architects stepped forward to claim the house. It was dismantled, moved to a botanical garden 30 miles away in the tourist town of Silverton and reassembled, under the supervision of architect Burton Goodrich, who apprenticed with Wright in the 1950s. The Smith's walked away with a nice tax deduction and a shiny new McMansion looming over the Willamette.

Wright would surely be bemused at the effort and expense that has gone into saving his buildings from the wrecking ball. After all, the Gordon House was one of his "low-cost" Usonian homes and was built for less than $10,000. Before it was over, the project ended up costing more than $1.2 million to relocate and restore the house. This is architecture as a kind of cultural fetish object.

A half-century after his death, Frank Lloyd Wright remains something of a brand name. And it's been that way since nearly the beginning of his career. Brendan Gill, writing in

Many Masks: a Life of Frank Lloyd Wright, suggests that many of Wright's clients didn't want a Wrightian solution to their architectural needs so much as they simply craved the Wright name attached to their house, thus inaugurating the birth of name brand architecture. During the early days of Wright's fame, there's little doubt that his older contemporaries, Daniel "Uncle Dan" Burnham, John Wellborn Root and Louis Sullivan, were equally, if not more, accomplished. But, among his many other talents, Wright was a genius at the game of self-promotion. He was the first architect as celebrity.

Wright was both a Utopian and a narcissist. He could jive talk his way through almost any crisis and there were many of them, usually of a financial nature. Wright was especially adept at snowing corporate titans, such as Herbert "Hib" Johnson, CEO of the Johnson Wax.

The Wright style with CEO's was unique, a full-frontal assault more than pandering. "He insulted me about everything," Johnson said of his first encounter with Wright. "And I insulted him. But he did a better job. I showed him pictures of the old office, and he said it was awful. He had a Lincoln-Zephyr, and I had one, it was the only thing we agreed on. On all other matters we were at each other's throats. If a guy can talk like that, he must have something."

Although they became very close friends, Wright didn't trust Johnson to present his plans before the Johnson Wax board. Hib Johnson agreed to let Wright attend the meeting, but warned him: "Please, Frank, don't scold me in front of my own board of directors."

Like most narcissists, Wright was an unrepentant mamma's boy, pampered and coddled by an attentive mother who told him he was a genius when he was three years old. Anna Lloyd-Jones Wright trained her son to be an architect almost from the crib, giving him the famous Freobel blocks that he continued to play with his entire life. Indeed, the floating planes of the Usonian designs seem directly traceable to simple structures made from wooden blocks that Wright would assemble in a matter of seconds on his desk to dazzle prospective clients.

The crypto-fascist Philip Johnson famously dismissed Wright as the greatest architect of the 19th Century. [Perhaps, architects who build glass houses shouldn't throw stones.] There's a certain grain of truth about this, though not, certainly, in the sense that Johnson, who embodied the worst strains of modernism (and post-modernism), meant to convey.

Wright was a utopian, in the grand romantic tradition. He was grounded in Rousseau and often let slip that his favorite poets were Walt Whitman and the dreamy Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Along with fellow poet (and snitch) Robert Southey, Coleridge cooked up an idea for a utopian community in western Pennsylvania they called, somewhat clumsily for two poets capable of stunning lyricism, the Pantisocracy. They were going to pay for the land on the proceeds of a long poem chronicling the life and death of Robespierre. But the plan ultimately fell apart over violent disagreements between the two on sexual freedom (which Coleridge advocated) and slavery (which Coleridge abhorred). Interestingly, the Pantisocracy, charted out only on maps in Coleridge's house in Keswick, was to have been located not far from where Wright built his most famous house, Fallingwater.

Wright also pored over Robert Owen's experiments in socialist communities, most notably in New Harmony, Indiana, where, as fate would have it, Wright's rival Johnson later built his open-aired church shaped like death's cap mushroom. But the class divisions and authoritarianism of Owens' community proved anathema to Wright's innate egalitarianism. He was more drawn to the Modern Times commune in Brentwood on Long Island, established in 1851 by the American anarchist Josiah Warren. Among other things, Warren's community was organized on the principles of "no police" and "free love", earning it the unyielding animosity of the snobs of New England who disgustedly referred to it as the "Sodom of the Pine Barrens."

The early half of the 19th century was a time of incredible optimism and radicalism in the United States. In the 1840s, there were 100,000 people living in more than 150 socialist/utopian communities across the country. "Those towns stood for everything eccentric: for abolition, short skirts, whole-wheat bread, hypnotism, phonetic spelling, phrenology, free love and the common ownership of property," wrote the journalist Helen Beal Woodward in 1945 article on utopian communities. The Civil War largely put an end to all that, but the utopian spirit continued to thrive after the war, particularly in the prairie states, through the rise of the populist parties and the Wisconsin progressives.

But it was good old Rousseau, perhaps more than anyone else, who seems to have shaped Wright's thinking the most. In one of his notebooks, Wright highlighted this passage from Emile: "Men are not made to be crowded together in ant hills, but scattered over the earth to till it." Throw in a free car (Wright preferred fast ones, such as Jaguars) and you've got the basis of Wright's utopian community, Broad Acre City.

Broad Acre City wasn't a design for a single community, as much as a kind of organic zoning plan for the entire country: a kind of motor-age update of Jefferson's vision of rural America. Wright believed each American family should be entitled to an acre of land and a car. The property lines and building sites would conform to the contours of the landscape, not the rigid grid system proposed by Jefferson and his followers and enacted in the famous survey whose consequences can be seen from any plane flying over the plains states. There would also be a pattern of greenspaces, community gardens, walking trails, parks and wildlands, concepts that he adapted from the English garden cities designed by William Morris.

Wright's idea was that each town would be self-sufficient, with growth limited by available water supplies and arable land.It wasn't until the 1910s that Wright began to think seriously about designing low-cost housing for working class people. But World War I and then the depression intervened. Then followed a real dry spell. Between 1928 and 1935, only two structures designed by Wright (other than his own house and studio at Taliesin) were constructed.

Then in 1935 Wright received a visit from Herbert Jacobs and his wife Katherine. Jacobs was a columnist with the Madison Capital Times, the city's most progressive newspaper. He was an admirer of Wright's work and wanted the great man to design their house. The problem was Jacobs was far from wealthy. Wright had little else on his plate and agreed to design a house that would cost $5,500, including his customary 10 percent fee. He called the design: Usonian.

What does Usonian mean? Who knows? Some suggest that Wright came up with the name during his first trip to Europe in 1910, when there was some discussion about referring to the USA as "Usona" in order to distinguish it from the new Union of South Africa. (In those days, as for much of the century, it's easy to see how the two nations could be confused.) Wright once said he took the name from Samuel Butler's utopian novel

Erewhon. But no one's been able to track it down there. (I did a word search of the online edition of Erewhon and couldn't find it.) Most likely it was a joke. After all, read in a mirror the title of Butler's novel is Nowhere.

Even so what Wright produced was little short of a revolution in American architecture: a beautiful structure, efficiently designed to sit on an odd (and cheap) lot, at a price affordable for lower income families. But the Jacobs House, and the dozens of Usonian designs that would follow, did more than that. It was truly one of the first environmentally-conscious designs, utilizing passive solar heating, natural cooling and lighting with his signature clerestory windows, native materials, radiant floor heating, and L-shaped floorplan that anchored the house around a garden terrace.The Jacobs house was an immediate hit in Madison, nearly as popular an attraction as the Johnson Wax Building, which was under construction at the same time further east, in Racine. On weekends so many people showed up at the door, the Jacobs began selling sold tickets to tour their new house. At fifty cents a pop, they quickly recaptured enough money to pay Wright's fee.

Over the next 30 years, Wright produced hundreds of Usonian designs, never wavering far from the original concept. "We can never make the living room big enough, the fireplace important enough, or the sense of relationship between exterior, interior and environment close enough, or get enough of these good things I've just mentioned," Wright wrote in a 1948 issue of Architectural Forum. "A Usonian house is always hungry for the ground, lives by it, becoming an integral feature of it."

The Usonian homes inspired great loyalty in their original owners. In 1975, John Sergeant did an inventory of the homes and found that over 50 percent were still owned by the original families, more than 35 years after construction. The same thing can't be said for his larger projects. The beautiful Robey House, near the University of Chicago, was inhabited for less than a full year, while Fallingwater served as little more than a weekend retreat.

So what happened? Why didn't the Usonian design take off? Why are we left only with the barest elements of the design, the cookie-cutter ranch houses that came to dominate the lots of suburban America?

There's no simple explanation. But one thing is clear. Wright's plans to revolutionize the American residential living space ran afoul of interests of the federal government. Think about this: in his 70-year career Wright didn't win one contract for a federal building. Not even during the heyday of the New Deal.

It all came down to politics. Wright's politics were vastly more complicated and honorable than that embodied by Howard Roark, Ayn Rand's self-serving portrait of Wright in her novel

The Fountainhead. Sure there was a libertarian strain to Wright, which Rand seized on and distorted to her own perverse ends. But he also was drawn to the prairie populism espoused by the likes of the great Ignatius Donnelly. It's this version of Wright that makes an appearance in John dos Passos'

USA trilogy.Wright was a pacifist and his outright opposition to war cost him government commissions, the great lifeline of the professional architect, especially during the Depression and World War II. Thus it's no accident that Wright was down and out most of his career. The high points came at the beginning and the end. He made more than 50 percent of his designs after he turned 70, and these weren't hack work, but some of the most innovative plans of any architect then working.

John Sergeant, in his excellent book on Wright's

Usonian houses, argues that there's a mutual admiration between Wright and the noted anarchist, Peter Kropotkin. In 1899, Kropotkin moved to Chicago, living in the Hull House commune, set up by radical social reformer Jane Addams, where Wright often lectured, including a reading of his famous essay the "Arts and Crafts Machine."

But, in those crucial decades of the 20s and 30s, Wright's political views seemed to align most snugly with Wisconsin progressives, as personified by the LaFollettes. In fact, Philip LaFollette served as Wright's attorney and sat on the board of Wright's corporation.

None of this escaped the attention of the authorities. From World War I to his final days, Wright found himself the subject of a campaign of surveillance, harassment and intimidation by the federal government. In 1941, 26 members of Wright's Taliesin fellowship signed a petition objecting to the draft and calling the war effort futile and immoral. The draft board sent the letter to the FBI, where it immediately came to the attention of J. Edgar Hoover, who already loathed Wright.Twice Hoover himself demanded that the Justice Department bring sedition charges against Wright. He was rebuffed both times by the attorney general, but, typically, that only drove Hoover to expand the surveillance and harassment by his goons.

But, as a review of Wright's FBI file reveals, the Fed's interest in the architect extended far beyond his pacifism. Hoover's men recorded his dalliances with the Wobblies, his continuing attempts to combat the US government's dehumanization of the Japanese during and after the war, his rabble-rousing speeches on college campuses, his work for international socialists and third world governments, including Iraq, and his rather unorthodox views on sexual relations (the Feds noted that Wright seemed to have a particular obsession with Marlene Dietrich).

It could be more sinister than ironic, then, that Carter H. Manny, one of Wright's apprentices at Taliesin West during the years when the architect and his cohorts were under the most intense scrutiny by the Feds, would go on to design the FBI headquarters (1963). The building, as conceived by Manny, exudes a bureaucratic brutalism that is far removed from anything that ever came off Wright's pen. Unlike most Taliesin fellows, Manny spent less than a year under the Master's tutelage, instead of the normal three. Some Wright devotees believe his tenure there had a more nefarious purpose.

The FBI wasn't the only federal agency giving Wright a hard time. Indeed, Hoover's snoops were only a minor irritant compared to the real damage that was done by the Federal Housing Authority, which routinely denied financing to Wright's projects.

There's no surer way to crush the career of an architect, particularly one trying to revolutionize the housing of working class people, than to cut off his clients' access to mortgages.The Federal Home Loan Association also refused to underwrite mortgages for Wright's houses, often citing Wright's signature flat roofs as a lending code violation. Here's a paragraph from one of the rejection letters: "The walls will not support the roof; floor heating is impractical; the unusual design makes subsequent sales a hazard." All bullshit, of course. But if there's anyway to kill architecture for working class people, it's to deny them loans.

A disgusted Wright wrote in his

autobiography that the federal government had "repudiated" his Usonian designs. In truth, it wasn't so much repudiation as flat-out sabotage. No paper trail has yet been discovered linking the FBI's harassment of Wright with the FHA's refusal to issue mortgages for his houses.

But it has all the hallmarks of a Hoover black bag job.There were other attacks on Wright. In 1926, the State Department even tried to get Wright's third wife, Olgivanna, deported as an undesirable alien. They were once again saved by the fast legal footwork of Phil LaFollette.

The IRS began harassing the architect in 1940, socking him with back taxes, penalties and interest dating back at least a decade.

It was the kind of bill that can never be paid off and it haunted Wright for the rest of his life. Even after he died, the Agency kept after him. In 1959, the IRS audited the Wright Foundation, which was the main funding source for Wright's troublesome colleagues at Taliesin. The Feds saw the Taliesin Fellowship as troublespot and wanted to extinguish it. It was after all a kind of commune, where the architecture students not only designed structures, but grew their own food, milled timber and ran a private school. [Not to mention the rampant bed-hopping.] Eventually, the tax agency forced the Foundation to sell off many of its most prized assets, including what remained after two awful fires at Taliesin of Wright's remarkable stash of Japanese prints, perhaps the best private collection in the United States.

Wright's plans to put portions of his Broadacre City model into reality ran into other problems with federally-connected lenders. Several of Wright's cooperative communities, including one in Michigan and another in Pennsylvania, came to nothing because banks refused to back the plan. The reason?

Wright and his clients refused to include restrictions prohibiting houses from being owned by blacks and Jews.***

Kimberly and I visited the Gordon house on a hot and muggy June afternoon. Hot for Oregon anyway. The house is now the feature attraction of The Oregon Garden, which bills itself as a world-class botanical garden. It's nothing of the sort. Indeed, it's little more than a permanent dog-and-pony show for the chemical agricultural industry and the timber lobby. There are better gardens in any old neighborhood in Portland or Eugene than you'll find here.

It was close to 90 outside, but inside the house remained cool, breezy, shaded by the jutting roofline. Wright detested air conditioning almost as much as contractors and academics. Even his home at Taliesen West, in the frying pan of Scottsdale, Arizona, uses natural features and architectural tricks to keep the building livable.

The Gordon House, like most of the Usonian designs, is a collage of Wright's influences: Japan, Central America, the curves, angles and tones of the American landscape itself. It is a beautiful mix of visual puns and little tricks of light as subtle and deceptive as a painting by Wright's contemporary, Eduard Vuillard.

The shape of the house is fairly simple. Wright called it a polliwog design, a t-shape with the kitchen and bedrooms massed in one section of the house, with the living room jutting out like the tail of a tadpole.

Even the design was political, reflecting Wright's disdain for contractors, those middlemen of the construction trade who do so little work but pocket so much cash, consequently driving prices through the roof. Wright wanted to do away with them, particularly at the level of the American home. In fact,

Wright wanted the Usonian houses to be so simple to put together that they could largely (and ideally) be constructed by the owner of the house. The prefabricated home becomes an extension of the Emersonian tradition.

One of Wright's dictum's for the Usonian designs is that the houses should "spring from the ground and into the light." By and large they do.

That's one of the most frustrating things about the migration of the Gordon house. It was originally designed to sit on a small bluff, with a view of the Willamette River to one side and the glacier-clad pyramid of Mt. Hood on the other. Each Usonian was different, fine-tuned to the site. The uprooted Gordon house seems alien to me, like a snow leopard I saw many years ago in the Cincinnati Zoo.

Once you take one step out of place, it's so much easier to take the next one. The restored Gordon House now sits over a basement. Wright hated basements and they certainly weren't part of the Usonian plan, which used a concrete floor mat laid over gravel and hot-water pipes as a source of radiant heating. The addition of a basement (in order to serve as an office for the docents) destroys the very nature of the house.

So what remains is really little more than a shell, a kind of exoskeleton of Wright's original house. Instead of being a low-cost home, it's now been transformed into a mauled museum piece, a model home for the path not taken in American residential architecture.

J. Edgar Hoover must be laughing as he roasts in Hell.

This essay is adapted from a chapter of Serpents in the Garden: Liaisons with Culture and Sex.

Reader Comments

Very interesting article, too.

FLW is yet another good reason not to fall into idiotic binary paradigm traps of the black/white, modernist/traditionalist, left/right, secular/religious, high art/low art kind. It does the business. It is the business.