The study also implies that most Americans are consuming a perfectly healthy amount of salt, the main source of sodium. But those who are salt-sensitive, about 20 to 25 percent of the population, still need to restrict salt intake.

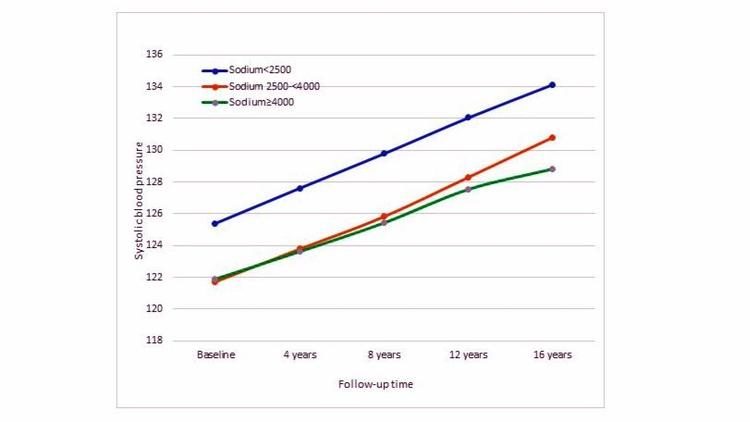

Consuming fewer than 2,500 milligrams of sodium daily is actually associated with higher blood pressure, according to the Framingham Offspring Study report, given today. The American Heart Association recommends consuming no more than 2,300 milligrams of sodium daily, equal to a teaspoon of ordinary iodized table salt.

High blood pressure is a known risk factor for heart disease and stroke. Hence, lowering salt intake is supposed to lower blood pressure and thus reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke. But the study found that supposition to be unfounded.

Moreover, the lowest blood pressure was recorded by those who consumed 4,000 milligrams or more a day — amounts considered dangerously high by medical authorities such as the American Heart Association.

Higher levels of calcium, potassium and magnesium were also associated with lower blood pressure. The lowest readings came from people who consumed an average of 3,717 milligrams of sodium and 3,211 milligrams of potassium a day.

The study is an offshoot of the groundbreaking Framingham Heart Study. Both are projects of the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute and Boston University.

The new report was delivered in Chicago during the Experimental Biology meeting by Lynn L. Moore, an associate professor of medicine at Boston University School of Medicine.

The report directly contradicts advice from the American Heart Association, which recommends consuming less than 1,500 milligrams of sodium a day to reduce blood pressure and risk of heart disease.

The American Heart Association justifies its recommendation on a 2001 study in the New England Journal of Medicine . The study is cited in a "scientific statement" by the association.

UPDATE

This story was originally published at 8:30 a.m. Tuesday. It was most recently updated at 2:30 p.m.

The NEJM study examined 412 participants for 30 days. They were randomly assigned to eat either a control diet or the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, which is rich in vegetables, fruits, and low-fat dairy products, in persons with and in those without hypertension.

The Framingham Offspring Study based its findings on a population of more than 2,600 men and women, whom it followed for 16 years. That means it can capture the long-term results of salt consumption, which the New England Journal of Medicine study couldn't do because of its short duration.

[...]

Biologically determined?

Moore said greater attention needs to be given to a hypothesis that people generally consume the amount of sodium they need. In other words, they are biologically driven to keep their consumption within a certain range.

The J-shaped curve implies that tampering with this drive could cause unforeseen health problems.

"There's evidence that salt restriction has a lot of effects on other systems other than blood pressure," Moore said. "You end up with higher levels of renin, rather than lower levels," referring to an enzyme that helps raise blood pressure.

"Other studies have shown that cholesterol goes up, triglyceride levels go up,. So there are a number of effects on known risk factors for heart disease that are independent of blood pressure, that seem to be activated in a setting of salt restriction," she said.

Growing evidence exonerates salt

Other reports in recent years have challenged the scientific basis of dietary advice on salt. These include a 2011 Cochrane Review study, a Sept. 2014 study in the American Journal of Hypertension, and in January 2015, in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommended that sodium intake be lowered to 2,300 milligrams per day for the general population. , The report is a joint project of the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services and of Agriculture.

However, a 2013 report by the Institute of Medicine specifically declined to endorse that limit, in part because the quality of information was insufficient.

"Overall, the committee found that both the quantity and quality of relevant studies to be less than optimal," the IOM report delicately stated.

But the carefully worded report also concluded that the bulk of the evidence indicates a correlation between higher levels of sodium intake and cardiovascular disease.

It also said there was insufficient evidence to conclude that lowering sodium intake below 2,300 milligrams per day either increases or decreases the risk of cardiovascular disease or death in the general population.

The 2015 version of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans repeats the recommendation to lower sodium intake to less than 2,300 milligrams.

The next edition of the guidelines is scheduled to be released in 2020.

Reader Comments

Happy to see the truth coming out!!

Podemos citar ainda que projetos de governo admitem que as pessoas estão vivendo muito, como dito pela Christine Legarde - FMI... ou seja, precisam morrer antes, para não causar prejuizo aos governos... Considerar ainda que uma das metas da Nova Ordem Mundial prevê uma redução da população dos atuais quase 7 bilhões de pessoas para 500 milhões de pessoas sobre o planeta Terra, precisando excluir 6,5 bilhões de pessoas, utilizando todas as formas possiveis... Parece que brevemente conseguirão atingir suas metas... se nós deixarmos...