When Roscoe Bartlett was in Congress, he latched onto a particularly apocalyptic issue, one almost no one else ever seemed to talk about: America's dangerously vulnerable power grid.

In speech after late-night speech on the House floor, Bartlett hectored the nearly empty chamber: If the United States doesn't do something to protect the grid, and soon, a terrorist or an act of nature will put an end to life as we know it.Bartlett loved to conjure doomsday visions: Think post-Sandy New York City without power - but spread over a much larger area for months at a time. He once recounted a conversation he claimed to have had with unnamed Russian officials about how they could take out the United States: They would "detonate a nuclear weapon high above your country," he recalled them saying, "and shut down your power grid - and your communications - for six months or so."

Bartlett, pictured with Nancy Pelosi in 2009, was by far the most conservative member of the Maryland delegation and was more than once called the "oddest congressman.

Bartlett never gained much traction with his scary talk of electromagnetic pulses and solar storms. More immediate concerns always seemed to preoccupy his colleagues, or perhaps Bartlett's obsessions just sounded more like quackery than real science, even coming from a former Navy engineer who had worked on the space race. Whatever the reason, Congress's failure to act is no longer Bartlett's problem. The octogenarian Republican from western Maryland - more than once labeled "the oddest congressman" - found himself gerrymandered out of office a year ago and promptly decided to take action on the warnings others wouldn't heed,

retreating to a remote property in the mountains of West Virginia where he lives with no phone service, no connection to outside power and no municipal plumbing. Having failed to safeguard the power grid for the rest of the country,

Bartlett has taken himself completely off the grid. He has finally done what he pleaded in vain for others to do:

"to become," as he put it in a 2009 documentary,

"independent of the system."Bartlett's newest cabin overlooks his manmade lake and will become his primary residence after he finishes the interior. He works on the cabin six days a week. The dining room, kitchen and living area will be heated by a large wood-burning stove.

I visited Bartlett this past fall, following a set of maze-like directions - take a series of different forks in the road and look for the one paved driveway that turns off a narrow, rocky dirt road - as I climbed to nearly 4,000 feet, one of the highest U.S. elevations east of the Rocky Mountains. I lost cell phone service halfway into the four-hour drive from Washington and never got it back. The nearest shopping mall is more than an hour's drive away.

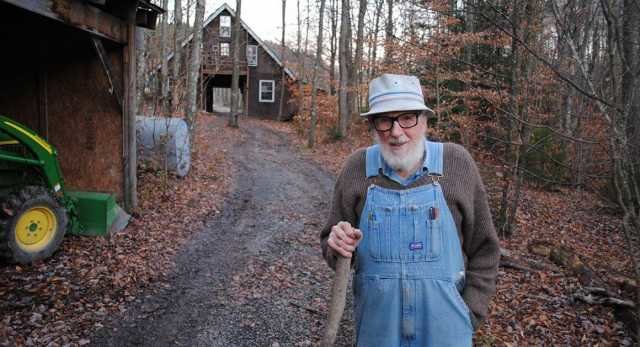

When I arrived, Bartlett greeted me in faded denim overalls and an unruly white beard and asked if anything had happened since he was last in Maryland, about a week earlier. I told him that the National Security Agency had just been caught tapping into the connections between data centers run by Google and Yahoo. He looked nonplussed.

Limiting the role of government consumed much of his life for the 20 years he spent in Congress, leaving little time simply to sit by his lake and watch the sun go down and the bats come out. But nowadays, his concerns center around when the next frost will come and keeping mice out of the food pantries

. He's more interested in pointing out the different species of trees on his property or showing off his new composting toilet than discussing Obamacare ("just awful") or the government shutdown ("lots of people realized we could get along just fine without the government")."You know," he said after a pause, "the news now is like a soap opera. If you miss it for a week, you haven't missed much."

"People ask me 'Why?'" Bartlett says as he is showing me around. "And I ask people why you climb Mount Everest. It's a challenge, and it's challenging to think what life would be like if there weren't any grid and there weren't any grocery stores. That's what life was like for our forefathers."

At 87, Bartlett hardly needs a reason to justify getting far away from the hustle and stress of Capitol Hill. There are no more votes to go back for, no more campaigning to do after nearly two decades as by far the most conservative member of Congress from the generally liberal state of Maryland. But he hasn't fully withdrawn from society:

Every couple weeks, he shaves, puts his suit back on and heads to Washington, where he serves as a senior consultant for Lineage Technologies, a cybersecurity group that seeks to protect supply chains. ("I don't need to work, but I want to be responsible," he says. "There are problems that need fixing, and I have some insight into these things.")

Bartlett's newest cabin overlooks his manmade lake and will become his primary residence after he finishes the interior. He works on the cabin six days a week. The dining room, kitchen and living area will be heated by a large wood-burning stove.

Not that his life out here in the mountains is anyone's idea of retirement. He rises at dawn every day except Saturday (he's a Seventh Day Adventist) and spends 10 to 12 hours cutting logs, tending gardens and painting walls. I ask Bartlett, as he climbs a ladder to an attic, if he has ever had any health problems. No, he says, besides a little arthritis and acid reflux. He may be pushing 90, but his weathered skin, hearing aid and walking stick are the only reasons you'd think he's gotten old. When his wife suggests we use "the Gator," a John Deere golf cart-like vehicle, to tour their refuge, he refuses, preferring to go by foot.

Bartlett is still proud of one of his first cabins, an exercise in sustainability and heating efficiency. He has since learned not to put solar panels on the roof: "You can't make adjustments when it's up there. The sun is 93 million miles away, putting it on the ground, a couple feet further away doesn't make a whole lot of difference," he says. Bartlett has Internet access via satellite but still no phone service. For that, the family has to trek more than a mile up the road, to a specific spot they call "the phone booth" that they've discovered has cell service.

Now he's midway through putting up a sixth house, a log cabin that will have a spacious kitchen, bathrooms with composting toilets, Internet access via satellite and a root cellar to store cabbage and potatoes through the winter. (Besides being more comfortable than his existing cabin, he needs the space to house his 10 adult children and their families, should his doomsday scenario come true.) The property also has a sawmill, a one-acre manmade lake with two pet swans, a gatehouse that arches over the long driveway and several gardens. It's surrounded by mountains and wild apple trees and bears and tiny plants called club moss that look like pine trees if you get close. He's got a mill for grinding flour, and on the day I visit his wife has whipped up potato onion soup made from produce grown in the garden and apple turnovers with apples that grow nearby.

Comment: Kudos to Congressman Bartlett for living a healthy sustainable life off the grid at a ripe old age.