Here are three surprising facts we've already learned:

1. C-G looks nothing like we'd expect

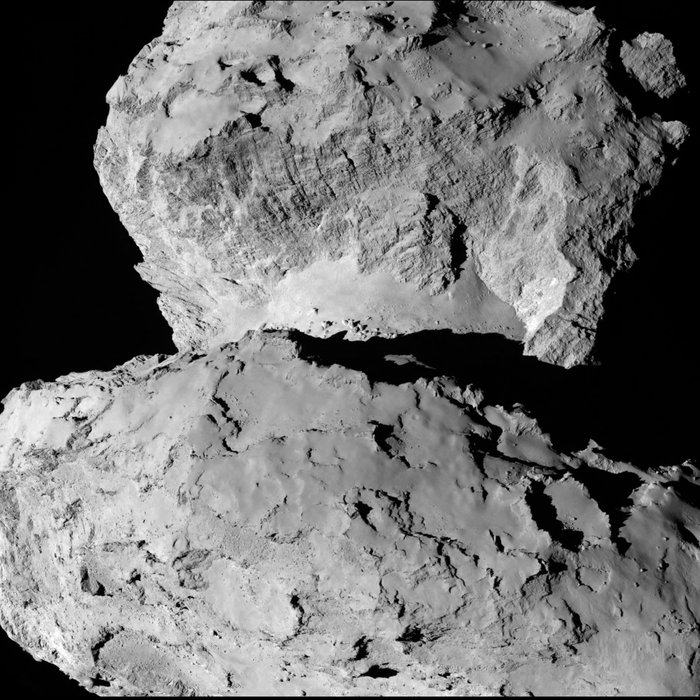

Holger Sierks, the lead scientist behind OSIRIS - Rosetta's 4-megapixel-camera - explains that while Rosetta has been approaching its rendezvous with C-G for years, the probe is only just now getting its first snapshots of the comet's core. "It took us up until June just to fill one single pixel of our camera," Sierks says. Now that the satellite is a mere 60 miles away, more recent images have detailed C-G's odd shape: something halfway between a rubber ducky and a lumpy potato.

"It was so surprising to see that this is not a [smooth], hull-shaped body, as we've thought it'd be," Sierks says. The scientists are still putting together why the comet might have such an odd shape. One possibility is that C-G is actually two comets that have been fused together, he says, although it's also possible the comet was somehow carved - through impacts or some other unknown force - into the strange figure.

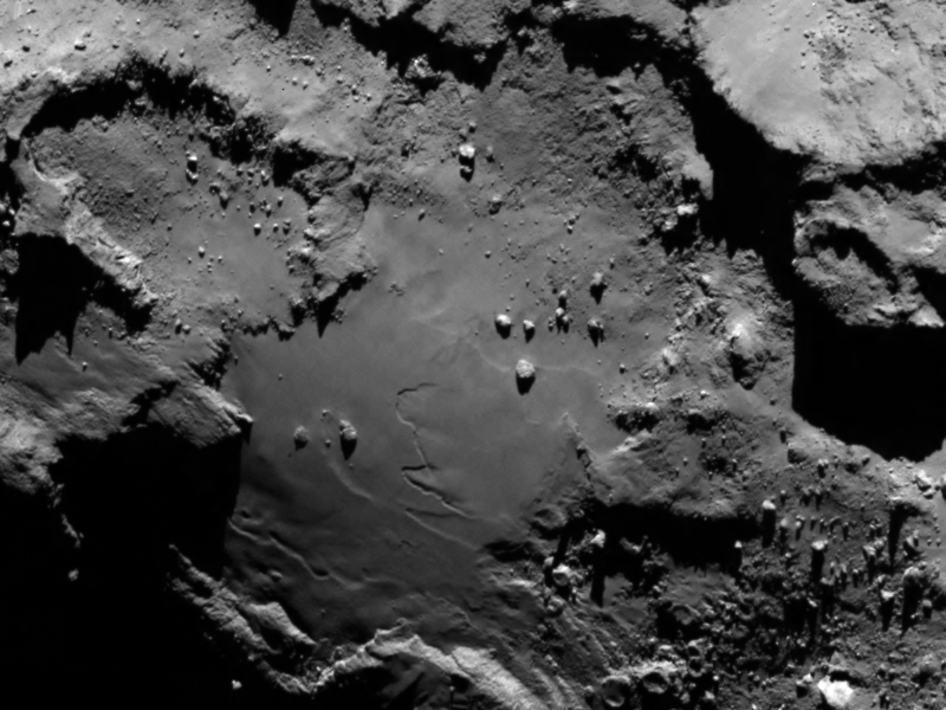

Comets are largely composed of rock and ice, but strictly looking at the surface of C-G might make you think otherwise: "We recorded a maximum temperature that's around [-63 degrees Fahrenheit]," says Fabrizio Capaccioni, the head of the mission's thermal imaging camera. That temperature is hotter than the researchers would have guessed, and "that tells us that the first [inch] of the surface crust is porous, dusty, and contains almost no ice," Capaccioni says.

This is a big surprise to the scientists, many of whom expected to find a glassy, clean surface of crystal ice. But the comet still is icy below the surface, "and we see water coming out, so there must be a way for the water to escape," Capaccioni says.

3. Despite its dry surface, C-G expels an astronomical amount of water... but not on its dark side

Samuel Gulkis, the head of Rosetta's water-tracking radio telescope, reported two months ago at a press briefing that C-G, though it is only 2.5 miles wide, expels so much water that "it would fill an Olympic-size swimming pool in about 100 days."

Today he's back with more data and reports that "one of the interesting things we've seen is that on the dark side of the comet, there's very little gas, [including water,] being produced." The facts about C-G's water content are perhaps the most pressing to the scientists involved. Cosmic questions ranging from where Earth's water came from to where and under what conditions comets like C-G originate all hinge on understanding the water on comets.

Comment: Here are the comments of physicist Wallace Thornhill:

It looks oddly like a spacecraft covered in rock and dust. Something like a shielding held onto the craft by a strong electro-magnetic source.