I don't know about you, but our annual switch to daylight time (called "summer time" most everywhere outside the U.S.) does amateur astronomy no favors. Most nights, by the time Sagittarius is up high enough to be seen well, I'm ready to put my head down for sleep.

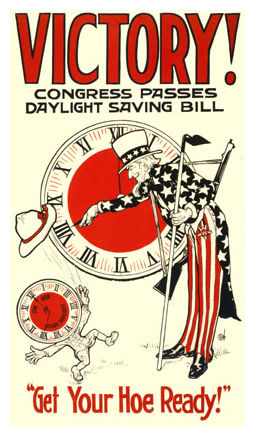

Things were bad enough - "springing ahead" in April and "falling back" in October - but a few years ago Congress meddled further with Mother Nature when it passed the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and decreed that daylight-saving time would be extended, beginning in 2007.

Now we make the switch from the second Sunday of March until the first Sunday in November, which is about two-thirds of the year. Canada followed our lead, but European countries wait another three weeks to make the switch and Mexico another four.

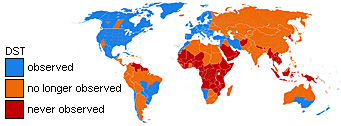

In fact, although about 75 countries observe some form of summer time, it's mostly a high-latitude phenomenon. Most of the world's population (150+ countries) avoids it altogether, and of course when northern countries are using it, our friends Down Under are not.

So how did all this come about in the first place?

But the tongue-in-cheek Franklin didn't propose changing clocks. For that, I blame golf.

Remarkably, this time-honored practice has been, and continues to be, controversial. Arizona and Hawaii keep standard time year round; until recently most of Indiana did too. Farmers don't like it. Backyard astronomers don't like it. The date switch in 2007 cost an estimated $500 million to $1 billion. Twice-a-year clock shifts cause confusion, disrupt your sleep, and, according to Swedish researchers, might even increase your risk of a heart attack.

The usual justification for advancing the clock is energy savings. The logic here is that by having more daylight in the evening hours, we use less lighting. But in 1966, when DST became the law of the land, air conditioning wasn't nearly as pervasive as it is now.

At the request of Congress, the Department of Energy analyzed the effects of daylight time's extension in 2007 and concluded that there might be an energy saving of 0.5%. But other findings challenge that assessment. Some studies show that daylight time causes us to use more energy, because we run the AC longer in late afternoon during summer and need more heat on sunless spring and fall mornings.

In October 2008 researchers Matthew Kotchen and Laura Grant (University of California, Santa Barbara) detailed what happened when Indiana caved in and adopted daylight-saving time in 2006. They find that Indianans' energy bills rose about 1% overall after the switch - and 2% to 4% in late summer and early fall. Kotchen told me increased energy use might prove even higher in the South (he's working on it), and he questions the methodology used in the much-touted DOE study.

So the debate goes on. If Congress listened to me instead of those clock-watchers at the Department of Energy, we'd do away with this time-warp nonsense. Let's stop this confusing annual ritual and bring a little more normalcy to our daily lives.

See the excellent article in Wikipedia for more information on Daylight Saving Time.

The longer daylight in the summer keeps people out later, so businesses benefit from it. The local businesses here change their hours of operation according to DST.