© Unknown

Progress, we tend to assume is, well, a Good Thing. Things that are new, and better, come to dominate and sweep aside old technologies. When they invented the car, the horse was rendered instantly obsolete. Ditto the firearm and the longbow, the steamship and the clipper, the turbojet and the prop. It's called the 'better mousetrap' theory of history - that change is driven by the invention of superior technologies.

Except it really isn't that simple. Sometimes a new invention, even if obviously 'better' than what came before takes a surprising amount of time to become established.

The first automobiles were clumsy, unreliable and expensive brutes that were worse in nearly all respects than the horses they were supposed to replace. The first muskets were less accurate and took longer to reload than the long- and crossbows which had reached their design zenith in medieval Europe. The last of the clippers were far faster than the first steam packets designed to replace them.

A fascinating essay in this week's

New Scientist points out that perhaps the second-greatest human invention of all (after language), that of farming, was not immediately successful at all.

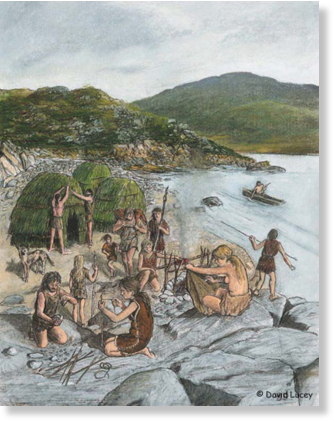

In fact the big switch from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to settled farming communities 11,000 years ago in the Neolithic had more to do with the creation of new social and economic structures than increasing food supply.It has long been realised that the advent of farming was not necessarily good for humans. Skeletal evidence tends to support the idea that the first farmers were shorter, weaker and died younger than their wild-foraging forebears.

Indeed, people have been shrinking for millennia since paleolithic times and only very recently have those in the rich world begun once again to approach the statures of our prehistoric ancestors. In his 2010 book

Pandora's Seed,

geneticist Spencer Wells argues that farming made humans sedentary, unhealthy, prey to fanatical beliefs and triggered mental illness.

© David Lacey

It is certainly true that large settled communities - possible only with specialisation of labour and organised food production - are more prone to diseases. Of course Stone-Age people got sick, but they tended not to get the plagues and epidemics that are associated with more recent history. A lot of this is speculation, but in his

New Scientist essay, Samuel Bowles, describes his quantitative analysis of the relative effectiveness of foraging versus farming - in terms of which provides the most calories for the least effort.

Using a whole host of data, collected by anthropologists studying hunter-gatherer tribes and analysing the effort needed to wield replicas of ancient farming implements, he has come to the conclusion that, like the first cars, the first farmers were no better than what came before in terms of feeding the masses.

Indeed, they were probably worse.

So why did we do it?

Farming, Bowles points out, ushered in a new era of property rights, created huge inequalities, paved the way for a wealth-based economy, divided the sexes and led to the creation of militaries needed to defend all this. Along with farming then, we got war and crime, madness and disease, cruelty, dictatorship and religions that were all about telling us what to do rather than emphasising our links with the Earth. The writer Jared Diamond has called

agriculture 'the biggest mistake humans have ever made' and it is tempting to see the story of the Garden of Eden and the Fall as an allegory for the descent of Man into settled barbarism.

It is a persuasive thesis. For most of our hundred-thousand-year history human beings have not lived as we live today.

Perhaps a great deal of our problems, from the modern plagues of depression and anxiety, obesity and environmental issues, can be ascribed to the Neolithic Revolution. In the end, though, there was no stopping the farmers. Along with the bad stuff we also got art, medicine, science and literature - all more or less impossible in a nomadic, Stone Age society.

Cars eventually got better than horses, guns won out over longbows and steamships overtook the graceful clippers. But the success of the new is rarely as obvious, at the time, as it seems with historical hindsight. A thought that must have occurred to those first labourers, breaking their backs on someone else's field, wondering why on earth they were doing this rather than picking fruit off a tree like their grandparents had done.

Methinks greed, rather than farming is the idea that so misshaped human history.

There are some valid points here, though. Such as where do we each draw the line in technological development? How much is it our free and makeable decision and how much is that decision made for us, by others?