© agsandrew/iStockphoto

The research, published in the journal

Nature Neuroscience, delves into a well-known genetic database -- the deCODE library of DNA codes derived from samples provided by the population of Iceland.

The authors first compared genetic and medical data from 86,000 Icelanders, establishing a DNA signature that pointed to a doubled risk for schizophrenia and an increase of a third for bipolar disorder.

The next step was to look at the genomes of people engaged in artistic work.

Those samples came from more than 1000 volunteers who were members of Iceland's national societies of visual arts, theatre, dance, writing and music. Members of these organisations were 17 per cent likelier than non-members to have the same genetic signature, the researchers found.

The finding was supported by four studies in the Netherlands and Sweden covering around 35,000 people, comparing individuals in the general public and those in artistic occupations.

Those investigations used somewhat different parameters but found the probability was even higher, at 23 per cent.

"We are here using the tools of modern genetics to take a systematic look at a fundamental aspect of how the brain works," says the study's first author Dr Kari Stefansson, head of

deCODE Genetics.

"The results of this study should not have come as a surprise because to be creative, you have to think differently from the crowd, and we had previously shown that carriers of genetic factors that predispose to schizophrenia do so," he says.

Source: Agence France-Presse

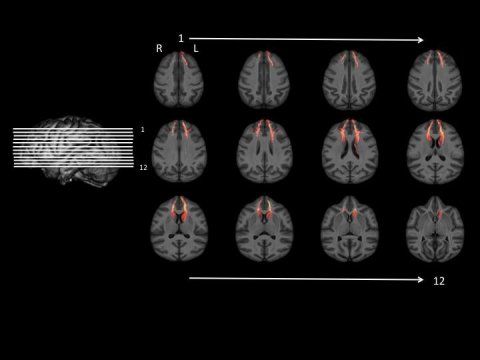

Comment: According to Dr. Peter Levine, the reason that animals in the wild do not experience ongoing trauma from dangerous encounters is that they have a spontaneous capacity for self-paced termination of the state of immobility induced by fear responses. When an animal comes out of the frozen state, it usually shakes and trembles, literally shaking off the state of immobility. However, when humans perceive they are in danger, their bodies assume specific defensive postures necessary for protection which are powerfully energized to meet extreme situations. When activated to this level and then prevented from completing the course of action - as in fighting or fleeing - our systems move into freeze or collapse, and the energized tension remains stuck in the muscles. In turn, these unused or partially used muscular tensions set up a stream of nerve impulses ascending the spinal cord to the thalamus and then to other parts of the brain signaling continued presence of danger and threat.

Fortunately, there are methods that can help to release stored trauma. Dr. Levine describes exercises that can help with the process in his book In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness. Another excellent method is the Éiriú Eolas breathing and meditation program that helps to effectively manage the physiological, emotional, and psychological effects of stress and helps to clear blocked emotions.