Remember the name Gunung Padang.

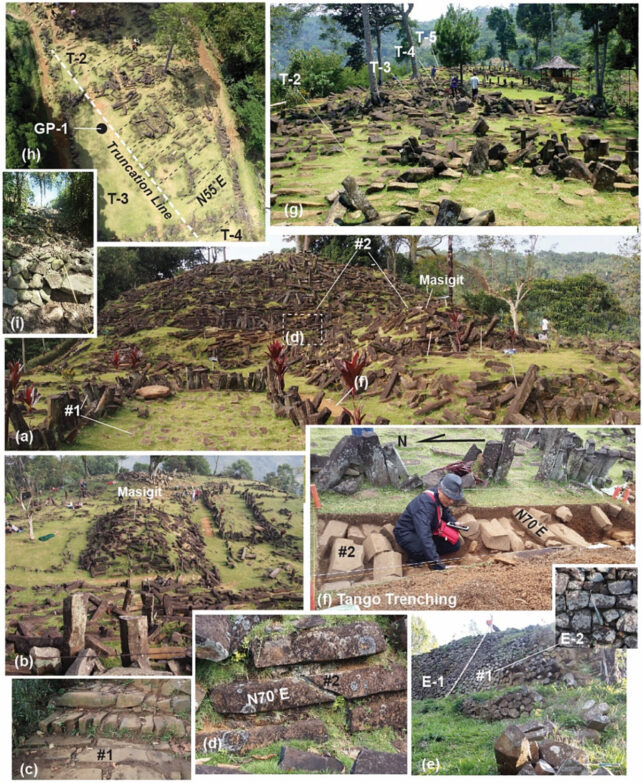

The exceptional hillside of ancient stone structures on the island of West Java is sacred to locals, who call this kind of structure a 'punden berundak', meaning stepped pyramid, for the terraces that lead to its peak.

Archaeologists have barely brushed the surface of the site, and yet it is already shaping up to be a "remarkable testament" to human ingenuity.

Gunung Padang is, potentially, the oldest pyramidal structure in the world, built atop an extinct volcano before the dawn of agriculture or civilization as we know it.

According to new data from scientists in Indonesia, its interior could very well be hiding large open chambers filled with unknowns.

The first radiocarbon dating of the site indicates that initial construction began sometime in the last glacial period, more than 16,000 years before the present and possibly as far back as 27,000 years ago.

To put that in perspective, Göbekli Tepe, which is a massive stone assembly in present-day Turkey, is currently considered to be the oldest known megalith in the world. It dates to 11,000 years ago.

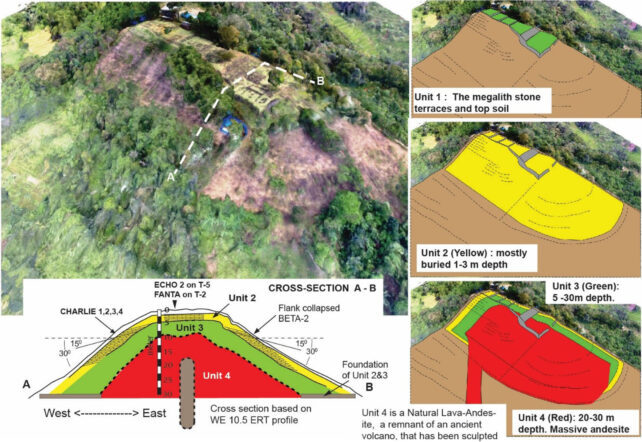

Between 2011 and 2015, a team of archaeologists, geologists, and geophysicists, led by geologist Danny Hilman Natawidjaja at Indonesia's National Research and Innovation Agency, used a variety of techniques, such as core drilling, ground penetrating radars, and subsurface imaging, to probe the cultural heritage site.

Natawidjaja and colleagues found like many megaliths in the past, Gunung Padang was built in complex and sophisticated stages, the deepest part of which lies 30 meters down.

Construction started again around 7900 to 6100 BCE, expanding the core mound of the pyramid with various rock columns and gravelly soils, with some further building work taking place between 6000 and 5500 BCE. Intriguingly, at this time, the builders seem to have purposefully buried or built over some older parts of the site.

The final architects of the pyramid arrived around 2000 to 1100 BCE, adding top soil as well as stone terraces characteristic of a punden berundak. This is the part that's mostly visible today.

"The builders of Unit 3 and Unit 2 at Gunung Padang must have possessed remarkable masonry capabilities, which do not align with the traditional hunter-gatherer cultures," write the team of researchers.

"Given the long and continuous occupation of Gunung Padang, it is reasonable to speculate that this site held significant importance, attracting ancient people to repeatedly occupy and modify it."

Further excavations are needed to understand who these prehistoric people were and why they built the things they did.

When researchers probed the interior of the hillside using seismic waves, they found evidence of hidden cavities and chambers, some up to 15 meters long with ceilings 10 meters high.

The team now hopes to drill down into these areas. If they do encounter any chambers, they plan on dropping a camera down into the darkness to see what lurks below.

"This study exemplifies how a comprehensive approach integrating archaeological, geological and geophysical methods can uncover hidden and vast ancient structures," the team concludes.

This won't be the last you hear of Gunung Padang.

The study was published in Archaeological Prospection.

Comment: Graham Hancock features Gunung Padang in his recent documentary series, Ancient Apocalypse.

See also: