In a

recent article I asked why U.S. intelligence officials were following the coronavirus outbreak in China in November 2019 when there is no evidence anyone in China was aware of or concerned about the virus at that point. I noted that no evidence had been produced to explain how they spotted it and why they were concerned.

Combined with a lack of cooperation with investigations into Covid origins and multiple signs of a cover-up, this unexplained early awareness of the virus is not just mysterious but suspicious.Since publishing that piece I have been

reminded about a

report from Harvard University produced in June 2020 (apparently with intelligence community involvement) that appeared alongside a companion

news report for

ABC News and showed

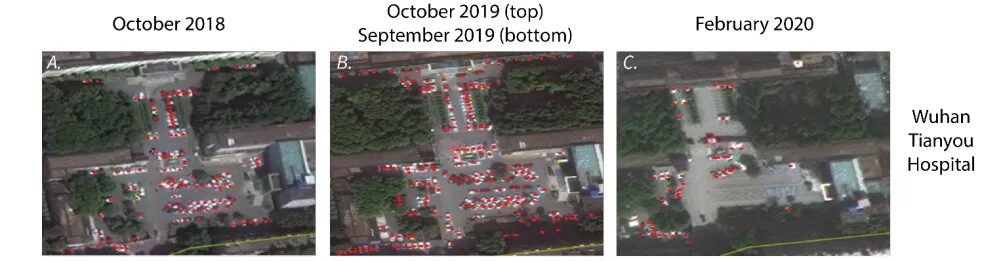

satellite images from Wuhan in the autumn of 2019 along with some data analysis, indicating increased hospital activity and other possible signals of disease outbreak.

The clear implication of the Harvard study is that these are the data (or some of them) that the intelligence community relied on in November 2019 to identify the outbreak and raise the alarm. The news report states the study used "techniques similar to those employed by intelligence agencies" and was "similar to work done by analysts at the Central Intelligence Agency and the Defense Intelligence Agency". The Pentagon's Chief Spokesman, Jonathan Hoffman, told ABC News he had "nothing to add" to the Harvard study, implying endorsement.

It's therefore worth asking whether the data in the study can account for the U.S. intelligence community's early awareness and alarm. Let's take a look.

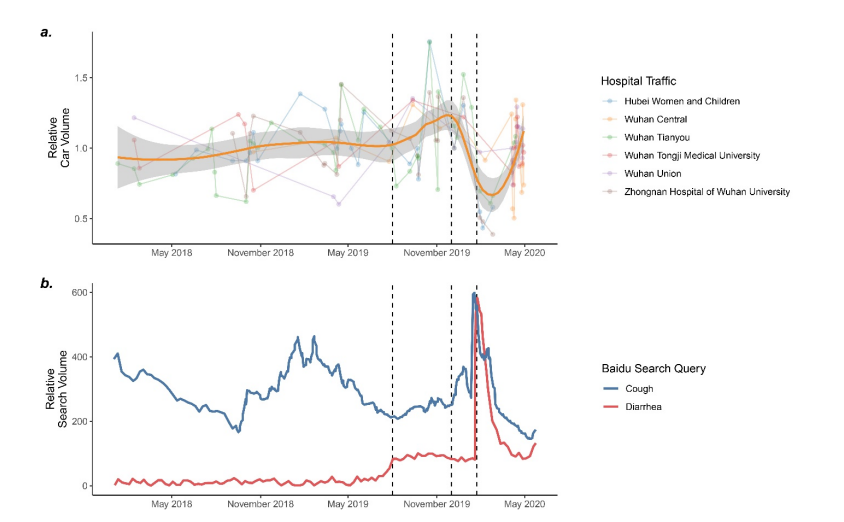

Here are the first two figures from the report.

The top chart (a) shows hospital traffic estimates from satellite images for six hospitals in Wuhan and an orange trend line that shows a smoothed overall figure. There is clearly a rising trend of overall hospital activity during October and November that wasn't present the previous year (note that the middle vertical dashed line is December 1st and the third vertical dashed line is January 23rd). So we seem to have here a signal of modestly increased hospital activity which may be indicative of an outbreak. However, on closer inspection, the fainter hospital-specific data points reveal that this extra activity was focused in two hospitals in particular: Hubei Women and Children and Wuhan Tianyou. The data points are also erratic, spiking for one data point in early November but dropping sharply again later in November before spiking again in December. It's fair to say this is not the clearest of signals. But perhaps the other data will be clearer.

The second chart (b) shows 'Baidu' search queries - which capture the frequency of internet and mobile phone searches - for 'cough' and 'diarrhoea' in Wuhan. The authors rightly draw attention to a signal of elevated searches for 'diarrhoea' after August (the first vertical dashed line). However, they also claim there is a signal for 'cough', but as can be seen in the chart, compared to the previous year no such elevated level of searches occurs prior to December. There is then a modest spike in searches for 'cough' during December, but even then it is well below the level of the previous year. In other words, there is no indication from these data of an outbreak of a coughing disease in Wuhan during autumn 2019, i.e., there is no Covid signal.

Noting the rise in 'diarrhoea' searches, the Harvard researchers suggest this means we should pay more attention to unusual symptoms in identifying a Covid outbreak. A more convincing conclusion, though, is that there was an outbreak of an unrelated diarrhoea bug during late summer and autumn in Wuhan. Such an outbreak may be sufficient to explain the increased hospital traffic at the time, particularly at the children's hospital - which would also be less likely to be explained by a Covid outbreak. At one hospital the traffic was shown to be particularly elevated in October (see below), which is way too early for the 'cough' signal, but fits with when diarrhoea searches were elevated.

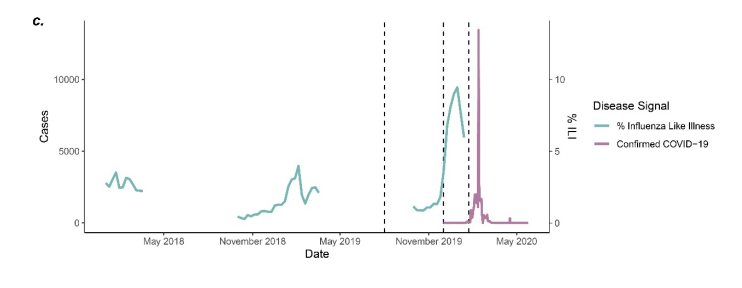

The third chart (c) from the report, above, shows the proportion of influenza-like illness admissions in two Wuhan hospitals. It again notably reveals a lack of admissions for influenza-like illness during October and November (prior to the middle vertical dashed line). There is then a spike in December, which matches the spike in 'cough' searches.

But, importantly, nothing in November when U.S. intelligence analysts claim to have spotted the Covid outbreak. This means, whatever was causing the elevated hospital traffic at some Wuhan hospitals in September, October and November 2019, it wasn't an influenza-like illness such as COVID-19.On these data, then, it's not at all clear how U.S. intelligence analysts could have seen a signal of a '

cataclysmic' outbreak of a respiratory virus in Wuhan in mid-November 2019 that they felt compelled to warn their Government and allies about.

There is no sign of a respiratory virus outbreak here - searches for 'cough' remained low in November and admissions for influenza-like illness were normal.In a way, this lack of signal from Covid is, we should note, unexpected. After all, we

know from other sources that the virus likely was already spreading both in Wuhan and more widely by November 2019, so we might have expected there to have been some signal for U.S. intelligence to have picked up on. On the other hand, we also know that this early spread was undetected everywhere at the time and did not cause large waves of hospitalisations and deaths.

Since no country including China appears to have spotted the virus spreading within its own borders during November 2019, the question of how U.S. intelligence spotted it in Wuhan (and only in Wuhan) remains salient.Thus this Harvard report, intended to show how U.S. intelligence analysts spotted the virus in November 2019 in China even though China itself had not noticed it yet, has ended up inadvertently revealing there was no signal of a respiratory viral outbreak in Wuhan at that time and thus no way that U.S. intelligence analysts could have spotted one.Naturally, this does nothing to diminish the growing

suspicions about how U.S. intelligence came to be following the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, and only Wuhan, at a time when no one else, including the Chinese, were even aware of its existence.

Comment: Maybe they knew about the virus before everybody else because they put it there. A lot of data tells us that the virus origin is probably from the US bio lab, not from China.

See also: