A senior epidemiologist who advised the government during the coronavirus pandemic claims he was told to "correct" his views after he criticised what he thought was an "implausible" graph shown at an official briefing.

Professor Mark Woolhouse has also apologised to his daughter, whose generation "has been so badly served by mine", and believes that closing schools was "morally wrong".

The Edinburgh University academic is deeply critical of the use of lockdown measures and says "plain common sense" was a "casualty of the crisis".

Speaking to Sky News, Prof Woolhouse seemed concerned about a possible "big-brother" approach to the control of information about COVID.

He says he was told to watch what he was saying following a briefing given by Chief Scientific Adviser (CSA) Sir Patrick Vallance on 21 September 2020.

Sir Patrick said at the time: "At the moment, we think that the epidemic is doubling roughly every seven days."

Fifty thousand cases a day were being predicted by mid-October.

"There was a lot wrong with the projection," Prof Woolhouse says. He calculated the doubling period as every 10 or 11 days, rather than seven, and, in his opinion, there was "no reason to expect the epidemic to accelerate suddenly".

He observes:

"If this projection had been extended for another week we would be talking about one hundred thousand cases per day. Another month would have given us close to half a million. Per day. An exponential projection will give you any number you like if you run it for long enough."Prof Woolhouse felt the predictions were "so implausible" that he was concerned about a loss of scientific "credibility".

After seeing the graph, he says he "quickly posted what was intended to be a reassuring comment through the Science Media Centre saying it was highly unlikely that the UK would see so many reported cases per day by mid-October".

"As it turned out, we barely reached half that," he says in his new book on the pandemic called The Year the World Went Mad.

However, his "objections did not go down well".

"After a flurry of emails I was invited to 'correct' my comments," he says.

"The invitation was passed on to me by a messenger so I cannot be sure precisely where in the system it originated."

Nor did not end there, he says. "A couple of weeks later I was asked to give evidence to a House of Commons Select Committee. This generated another flurry of emails over an October weekend from two senior government scientists concerned that I might criticise the CSA's graph before the MPs."

When asked where the message telling him to "correct his views" came from, he says he simply doesn't know the source, but it was "not from a random person".

Clearly angry, he insists it "wasn't my views that needed correcting, it was the projections".

Prof Woolhouse says restrictions imposed on children were 'morally wrong'

21 September saga 'played out again' on 31 October

In a news conference on 31 October 2020, Prof Woolhouse says that "almost unbelievably" the "September 21st saga was played out again".

A chart was presented predicting 4,000 deaths a day - several times higher than during the previous peak in April.It "presaged the prime minister's announcement of a second lockdown in England", Prof Woolhouse writes. But it "quickly became apparent that this projection was already inaccurate on the day it was shown".

Nor did it take into account the "fact that the second wave was already beginning to slow".

The Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling (SPI-M), on which he sits, uses "ensemble modelling" - that is, different teams, including Prof Woolhouse's own, calculating their own scenarios.

He writes: "The model that generated the 4,000 deaths a day figure was an outlier - all the other model projections gave much lower numbers."

But, somehow, that was the one shown to millions of TV viewers.

Prof Woolhouse says: "Many people believed that England had gone into lockdown on the basis of a 'dodgy dossier' - a term used for a somewhat similar episode in the build-up to the Iraq War in 2003."

A government spokesperson told Sky News: "The government ensures a wide range of evidence and insights are considered as part of the COVID-19 response.

"SAGE delivers a consensus view based on the best available evidence at the time bringing together scientific experts from a range of disciplines, including epidemiologists, clinicians, public health experts, virologists, data scientists, mathematical modellers, statisticians and genomic experts."

The R number 'monster'

The R Number, or reproduction number, became a prominent part of the coronavirus discussion.

But most of the politicians and commentators who discussed it had "never heard of R before the pandemic began and clearly didn't understand it", Prof Woolhouse says.

It "only refers to infections, so it doesn't tell you about the numbers of hospitalisations and deaths, which matter most to the NHS and government".

"Nor does R help anyone understand their individual risk, which matters most to you and me," he continues.

"As one of my colleagues put it: we've created a monster."

Emergence from third lockdown based on 'dates not data'

Prof Woolhouse supported the first lockdown, in March 2020, partly because there was "no other option on the table".

He was taking part in a meeting of SPI-M, which reported to SAGE.

"It was a sombre moment," he writes.

He does not play down the seriousness of the virus, describing it as "an extraordinary event that demanded an extraordinary response and got a very ordinary one".

The main question he asks is: were lockdowns the correct approach? A "robust public health response" was required, but the "issue" was "whether that response had to be lockdown".

SPI-M was "never asked to model alternatives to lockdown", he says.

There was a lack of debate about the use of lockdown measures "from the very beginning", and England's emergence from its final lockdown, last year, was based on "dates not data", he contends.

"By February 12th (2021), more than 95% of everyone over 70 years old had had their first dose" of a vaccine, he says.

A few days later, he told a committee of MPs that the "data on both virus and vaccine were not merely encouraging, they were far better than anyone had been expecting when the lockdown began".

The dates, though, were not brought forward.

Worst-case scenarios treated as 'predictions'

At the beginning of the pandemic it was feared that as many as 500,000 people in the UK might die of COVID.

That figure came from Imperial College's Report Nine, based on the premise that literally nothing would be done to protect people from coronavirus - that life would carry on as normal.

That vital nuance, however, appears to have been lost on many.

It was "condensed to the simple but misleading message that, if the government didn't impose full lockdown immediately, over half a million people would die", Prof Woolhouse writes.

But behaviour had already changed before Boris Johnson made his announcement to the nation on 23 March 2020, the professor tells me from his home in the Scottish capital.

Mobile phone data provided by Apple and Google, detailing the patterns in people's movements, show there were "marked shifts in people's activity patterns in the week before 23 March, with many more people apparently staying at home".

Thus "lockdown itself seems to have come late to the party and had surprisingly little effect", while people change their behaviour "regardless of what government does", Prof Woolhouse contends.

The Imperial College model "wasn't remotely realistic" and anyone who supported the first lockdown on that basis "was misled", he adds.

But the media "cannot resist" treating a "worst case scenario" as a "prediction", he notes ruefully.

"Peaks (in cases and deaths) were headlines; troughs went straight to the middle pages.

"Unless you were paying close attention you could easily get the impression that the epidemic was growing much faster than it was."

People over 70 '10,000 times more likely to die from COVID than those under 15'

On 27 March 2020, cabinet minister Michael Gove said during a Downing Street news conference that COVID "does not discriminate".

But Prof Woolhouse says it was known from quite early in the pandemic that people over 70 were 10,000 times more likely to die from COVID than those under 15. That figure is now reckoned to be even higher, he tells me.

And Prof Woolhouse says, in a roundabout way, that the CCTV camera in the Department of Health that caught Matt Hancock kissing his lover did the UK a massive favour - that after his resignation, in late June 2021, the Westminster government finally accepted that we were "living with COVID".

As far as Prof Woolhouse is concerned, we have been living with COVID since "February 2020".

Scientific advisers became lockdown 'advocates'

Prof Woolhouse is clearly troubled by the behaviour of some of his fellow scientists during the pandemic.

He writes:

"I recall one advisory group meeting where those of us favouring the relaxation of lockdown measures were characterised as being more willing to take risks.In the lead up to the second lockdown in England, he says that

"The comment was well intentioned but I strongly disagreed with it. I think we were all similarly concerned about the potential impact of novel coronavirus. The bigger difference was that some were more concerned than others about the risks of harm caused by lockdown."

"Throughout 2020, many scientific advisors were all too willing to dismiss those indirect harms."

"[O]ne adviser after another from SAGE and other committees were calling for lockdowns at very early stages - it was continual - a stream of them doing so".How much did schools contribute to transmission?

"The government didn't want to go back into lockdown, but we seemed to end up with a sort of impasse. The calls for lockdown type interventions got louder and louder and the government resisted for as long as it could and it was eventually, essentially, forced into implementing the November lockdown.

"The evidence is that that particular peak was already coming down before the lockdown was implemented. A more modest intervention earlier would have negated the need for that November lockdown."

"Some advisers who went on the media a lot went into advocacy rather than advice."

The Office for National Statistics has done surveys which showed teachers "were not at increased risk of infection compared with other professions", Prof Woolhouse says.

He adds:

"There wasn't much evidence when we first closed the schools that they were contributing much to transmission, and the evidence from Australia was that they weren't - they'd had some outbreaks in schools and studied them.As a parent, he is

"SARS (another coronavirus) didn't spread well in children or schools either."

"There was a contribution from schools to transmission but it is very modest - it's there, it's not nothing, but it is modest.

"We could have kept schools open and still kept the R number below one."

"deeply uncomfortable with the fact that our strategy to tackle novel coronavirus did such serious harm to children and young adults".What were the alternatives to lockdown?

"We deprived them of their education, jobs and normal existence, as well as damaging their future prospects and leaving them to inherit a record-breaking mountain of public debt.

"To me, it seems morally wrong."

Given that it was known from early in the pandemic that the elderly were vastly more at risk, Prof Woolhouse says there should have been more focus on the vulnerable.

Those in favour of lockdowns - of treating the wider population equally - argued that vulnerable people needed to see others, and that some of those others might have been going out and mixing.

Prof Woolhouse says the answer was to protect both the vulnerable and to support their contacts.

Research has since been done on such an approach and it could have been made to work, he says.

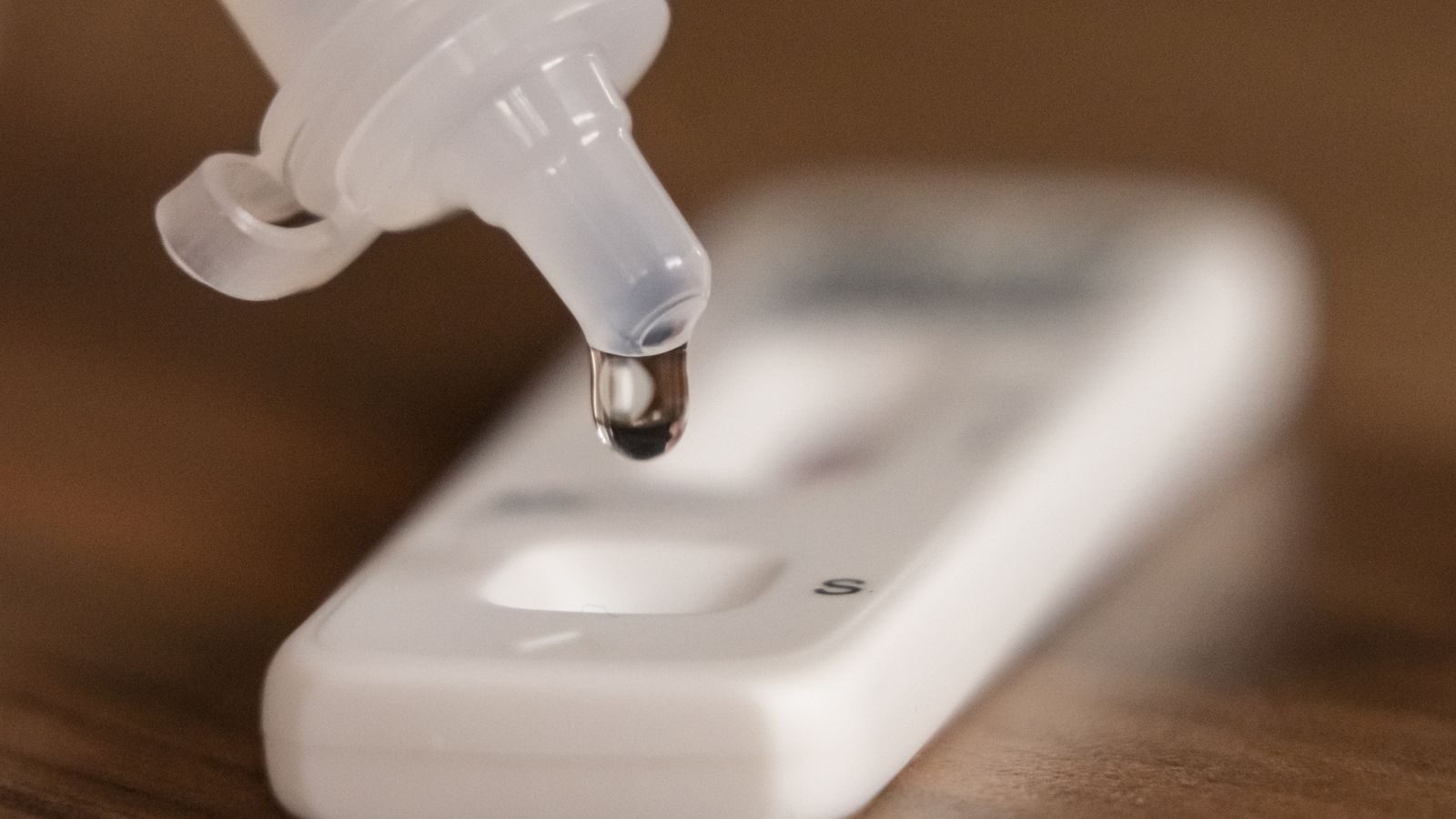

He also says that lateral flow testing should have been ramped up much more quickly - the technology was available from late summer 2020.

But Prof Woolhouse points out that it was not trialled "at scale" until the following November in Liverpool.

He describes it as an "incredibly valuable technology for reducing transmission rates".

He thinks it was a major factor in keeping us out of lockdown during the recent Omicron wave, with more than 80% of people testing at least once a week.

"We should have given (LFTs) the same urgency we gave the vaccines," he says.

Comment: