Anyone who imagines the Highlands 2,000 years ago to be wild, woolly and primitive should think again.

The newly-published findings of an archaeological dig at Culduthel, on the southern outskirts of Inverness, have revealed an Iron Age craft village manned by exceptionally skilled artisans, producing goods from iron, bronze and glass for international trade.

The dig was carried out by Headland Archaeology prior to a housing development by Tulloch Homes.

The excavation team at Culduthel, Inverness. Supplied by Headland Archaeology.

The site had distinct phases and at least 17 round houses, showing metal working on a scale previously unseen in Scotland.

Radiocarbon dating shows activity from around 3760BC to AD340, in three clear periods of activity.

Extraordinary insights

A new book by Headland's Candy Hatherley and Ross Murray brings together 20 years of painstaking research into the finds to share extraordinary insights into life between 200BC and 200AD in the Moray Firth.

Their verdict on the Culduthel community?

Well-organised, talented, artistic, well-travelled, sophisticated artisans, connected into complex trading networks, including contact with the Roman world.

"It's the earliest specific craft centre in the Highlands. They might have been living close by, but on that site they're purely making things like tools for leather working and textile working, tools to do glass working - we found a tool that is effectively for taking moulten glass and spinning it round into a bead.

"We also found a pair of snips or scissors, a variety of knives, all from iron so we can really tell how they're making stuff and also what they're making."

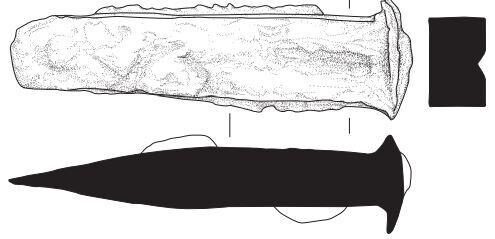

"We found a part of a chariot they've made in iron. It fits onto the axel of the chariot to hold the wheel in place," Candy said.

"We can tell they were doing wood-working as we found lots of iron tools for wood-working like miniature axes, chisels, the whole lot, a wonderful array which lets us see exactly what was going on.

"They are specialising making iron objects to then exchange or trade, or to use in the settlement itself for leatherworking, wood working or potentially chariots."

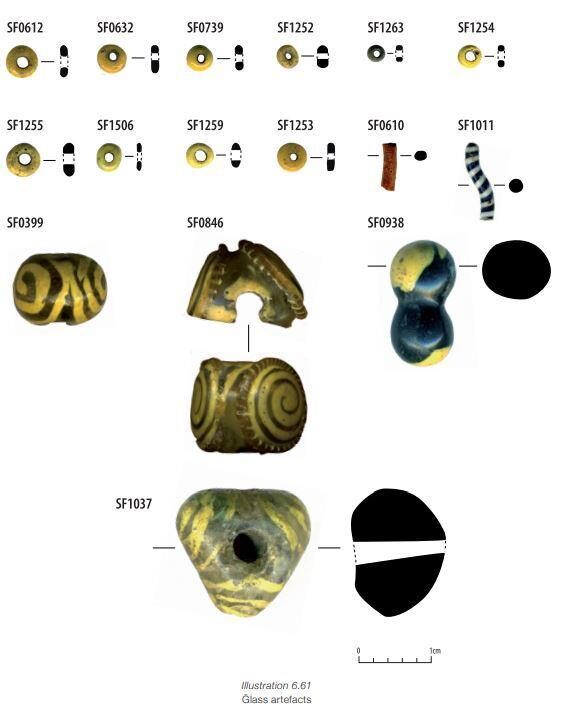

The team were blown away by the beauty of the glass beads they found on the site.

Candy said: "They're just beautiful and these glass beads are found in Orkney, Shetland, all over Scotland and some have been found in England as well, not necessarily made on the site but exactly the same type of beads is getting distributed all over Scotland certainly, and they're making them on this site."

Bronze bling for horses

Not many of the artefacts found on the site made of bronze were completed, but one stands out.

Candy said: "It's a harness strap mount, a bit of bling for a horse if you like.

"You put a harness on a horse and then slid the decoration onto it, where it would have sat round about the horse's cheek.

The level of sophistication of work going on the site amazed Candy and the team.

She said: "This demonstrates that this isn't an isolated little Highland village, this is somewhere that is very well connected with the rest of the British Isles.

"It's on the edge of the Great Glen so it's probably connected by sea with the west coast, the Irish Sea and out through the Moray Firth to Norway.

Trading with Romans

"They're probably trading significantly with the Romans by the first couple of centuries AD.

"They may not have been meeting the Romans themselves, but they are probably meeting tribes who have had goods through the Romans.

"At that time the Romans were trying to woo the tribes of the north so they were probably giving them quite a lot of gifts, like coins which of course weren't useable for an Iron Age tribe in Inverness, and bling, including brooches, bits of glass for re-melting down."

Artistic influences

The bronze work going on on the site shows artistic influences from right across Britain, Candy says.

"They're not just a bunch of pre-historic men living in the middle of nowhere, actually these people are at the forefront of arts and crafts abilities of the middle Iron Age."

Excavating the iron smelters found at the Iron Age craft village at Culduthel, Inverness. Supplied by Headland Archaeology.

"When we were stripping the site you could see upstanding walls, furnaces that would have been used to smelt the iron ore to be used by a blacksmith to make the tools.

"I've never seen anything like it. There was so much iron waste lying about it was immediately apparent that this was going on on a big scale."

Abandonment

No one knows why the site was abandoned, but the archaeologists think the settlement and its industrial practices were left wholesale, and not relocated further afield.

Many reusable items were found left on the site including iron tools, rods of glass and sheets of copper alloy.

The timbers of the large houses and workshops were left to rot in situ, and the furnaces and hearths were undisturbed.

Over time, the mounds of industrial debris on the site slumped and spread across the site, eventually flattened and covered by hill wash, until two millennia later, modern humans decided to build houses on it for the rapidly expanding city of Inverness.

The finds will go before the Treasure Trove panel in Edinburgh, and Candy hopes they will eventually make their way back home, to the museum in Inverness.

Comment: See also: