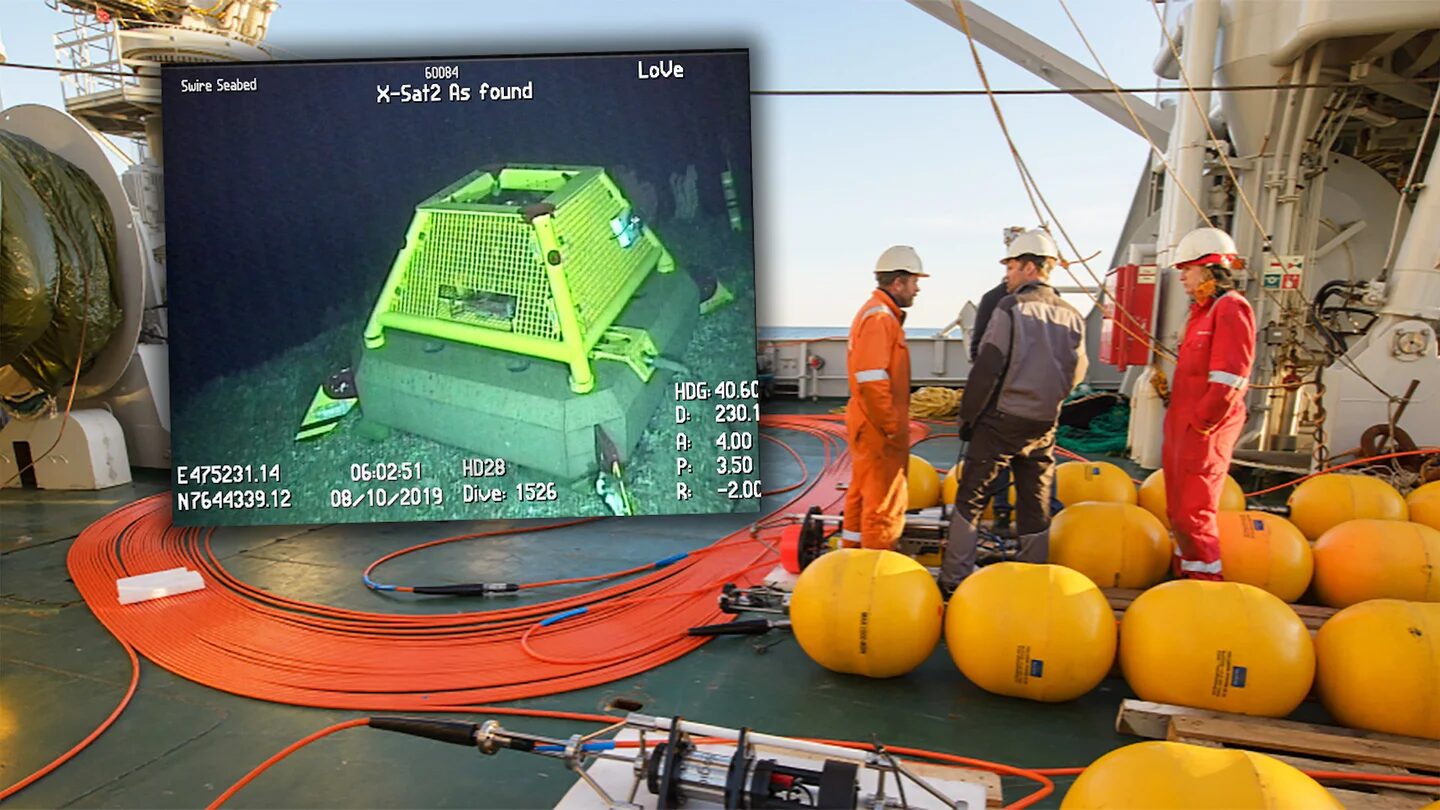

The Norwegian Institute of Marine Research (IMR) reported the breakdown just before the weekend, blaming it on "extensive damage" to its outer areas. Known as the Lofoten-Vesterålen (LoVe) Ocean observatory, it comprises a widespread network of cables and sensors on the Norwegian Continental Shelf that IMR describes as "infrastructure for research and surveillance of the ocean area." Platforms placed on the sea floor are equipped with scientific sensors that measure methane emissions and signs of climate change in the sea, follow fish behaviour and also send live photos and sounds from their surroundings.

The area itself is home to rich fishing grounds and also is considered so strategically important that the underwater damage has been reported to police. "Something or someone has torn out cables in outlying areas," stated LoVe project leader Geir Pedersen in a press release on Friday. That cut power to the entire system, in which the cables connect the platforms, also called nodes, that provide constant surveillance of important subsea areas and send all the information back to land.

Officials running the system first though the trouble stemmed from a cut in power supplies, but attempts to restore electricity to the offshore network failed. When technicians couldn't find any errors in the system close to land, they had to venture farther afield.

After spending the rest of the spring and summer trying to find the error, aided by help from state oil company Equinor that had invested in the NOK 150 million underwater observatory project, the trouble was finally linked to "Node 2." A remote-controlled research submarine found that the Node 2 platform at a depth of around 250 meters had been dragged out of position. Its cable was cut and could not be located.

Then, on September 30, Equinor sent another vessel out to the site above "Node 3" that had been connected to "Node 2." The goal was to try to follow its cable back Node 2, but instead came up information that Node 3 had also been moved out of position, its contacts and connection box were torn off and its cable was missing.

"This was quite a shock," Pedersen told DN. "I could see that this was quite serious, more serious that we had hoped, and that it would require lots of resources to get the system up again."

Live pictures from the site in late September clearly showed that there no longer was any cable connected to Node 3. It was as if a plug had been torn out of its sockets, according to IMR director Sissel Rogne. "This was a very thick cable, and very, very heavy," Rogne told DN. Only something very powerful could have torn off the cable from both nodes, and carried it off. Fully 4.3 kilometers of the 66km cable network were missing.

The area where the cables could record and photograph everything moving through it, from fish to submarines, is of such strategic importance that all sound and photos captured by the sensors, nodes and cables were always sent first to the Norwegian Defense Department's research institute FFI before being freed for examination by IMR. FFI won't comment on the damage, nor will local police who were alerted to it.

Not only is the area important as the location for lots of fish breeding, it can also attract military submarines from both the Norwegian Navy, NATO allies and other countries. Ripping out the cables left the entire underwater observatory and its surveillance system out of play. All intelligence information that could have been recorded first by FFI was gone. The system monitoring the entire underwater area has remained down since last spring.

"The most important thing for us right now is to find out whether someone has actually attacked the cable," Øystein Brun of Norway's research institute told DN, "and whether it's possible to prosecute whoever has destroyed this cable for us."

Brun of IMR believes that even if the cable was torn accidentally, whatever vessel did it should have noticed the incident. The other mystery is what has become of the 9.5 tons of missing cable itself. "This has happened (sometime around April 3), through an act with considerable power behind it," Brun said, adding that it's customary for vessels to report any such incidents or accidents to the authorities. No such reports have come in.

Efforts have been made to identify vessels in the area last spring, but they can also turn off the systems that made their presence known to the Coast Guard, the IMO or commercial systems like Marine Traffic. If the cables were torn through a deliberate act of sabotage or for espionage reasons, it's unlikely their so-called AIS senders would have been activated.

Not only has IMR reported the damage to local police as required but IMR's director Rogne also contacted PST and the government ministry in charge of business and fisheries. FFI is believed to routinely remove traces of any submarine activity in the area before turning over the observatory's data to IMR so that it only contains fishing, currents and climate information.

"We don't care so much about the submarines in the area (located not far from onshore military installations at Andøya, Evenes and other bases in Northern Norway), but we know the military is," Rogne told DN. She thinks it's important that PST be aware of all the information that flowed through the cable system that's been rendered unusable now. It's possible foreign governments could be interested in underwater surveillance information picked up by the cables, or simply the cables themselves, since they reflect unique Norwegian technology that could be useful elsewhere.

Or someone may have just wanted "to ruin how the information was sent," Rogne told DN. It could have measured submarine activity "or other activity in the area, in real time. You could see what's going on down there regarding all types of U-boats and all other countries' U-boats. That's why I didn't think this was just a case for the police but a case for PST. And now our research infrastructure is out of order, too."

Ships in the area that had their tracking systems activated during a six-hour period on April 3 when the damage is believed to have occurred have been identified. PST officials told DN that they don't want to comment on the case yet, while both FFI and local police are also staying mum. No suspects have been identified, but DN also has reported about lots of Russian shipping activity in the area of late, often cropping up around Norwegian offshore infrastructure. The activity is legal, but not especially welcome.

Comment: It's revealing that they state they don't like Russian shipping acitivity in the area - despite it being perfectly legal and the PST having no legitimate complaints - meanwhile they've no issue with 'NATO allies and other countries' going about their business.

Pedersen, in charge of the observatory project, notes that the damage "will cost a lot to repair. We don't know where the cable is, we expect we probably need a new cable (to hook up at least parts of the system again) and it's uncertain whether whether the connection points can be reused."

He said marine research institute IMR, meanwhile, plans to send its own research vessel G.O. Sars to the area in the hopes of examining the site more closely, and try searching for the cable. IMR receives fully half of its funding from the government and the rest from private sources, like Equinor or research funding grants. Pedersen said he hopes at least part of the underwater observatory system closest to land can be reconnected, also that which extends over the entire Norwegian Continental Shelf.

Could it be that Godzilla has returned ? Or is there a deliberate attempt to restrict access to data that is proving to be too revealing.