The researchers re-analyzed previously published DNA data from ancient humans that lived during the last 45,000 years to find out how closely related their parents were. The results were surprising: Ancient humans rarely chose their cousins as mates. In a global dataset of 1,785 individuals only 54, that is, about three percent, show the typical signs of their parents being cousins. Those 54 did not cluster in space or time, showing that cousin matings were sporadic events in the studied ancient populations. Notably, even for hunter-gatherers who lived more than 10,000 years ago, unions between cousins were the exception.

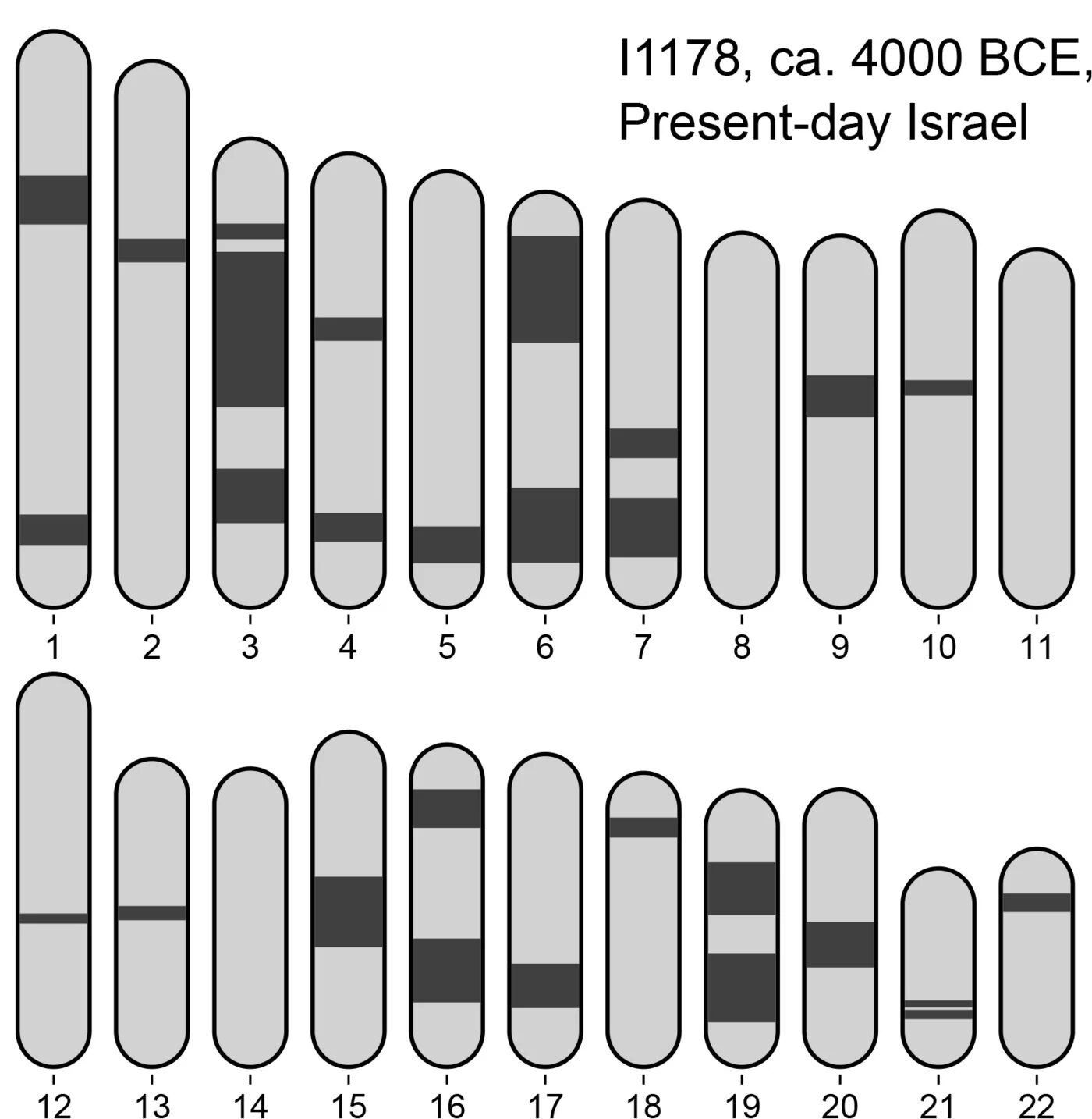

To analyze such a large dataset, the researchers developed a new computational tool to screen ancient DNA for parental relatedness. It detects long stretches of DNA that are identical in the two DNA copies, one inherited from the mother and one from the father. The closer the parents are related, the longer and more abundant such identical segments are. For modern DNA data, computational methods can identify these stretches with ease. However, the quality of DNA from bones that are thousands of years old is, in most cases, too low to apply these methods. Thus, the new method fills the gaps in the ancient genomes by leveraging modern high-quality DNA data. "By applying this new technique we could screen more than ten times as many ancient genomes than previously possible", says Harald Ringbauer from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, the lead researcher of the study.

Studying background relatedness

The new method to screen ancient DNA for parental relatedness gives researchers a versatile new tool. Looking forward, the field of ancient DNA is quickly developing, with more and more ancient genomes being produced every year. By elucidating mating choices as well as the dynamics of past population sizes, the new method will allow researchers to shed more light on the lives of our ancestors.

Reader Comments

[Link]

I dunno man.. have you ever met any of my cousins?

[Link]

[Link]

R.C.

[Link]

[Link]

But I never forget - 2001 was they year they cut out bank accounts by half ...

And not a half year had passed since the € - introduction, and food and fuel prices had gone up about 30%. Hence the name nickname Teuro.

20 is Mouse... (Mom had 1, 1946🤔)

Germany Russia USA Eagle Totem right.

Owl is called Night Eagle.

That was my 1st reflection and thought better not here.

Castration also keeps the feet from growing out normal size. ANDdddd the men from attaining their potentiality of Spiritual YANG growth. IT remains stunted (for this LifeTime) unless excessive and constant prioriry given to it. (Which must be unseen/unheard of).

Crazy but TRUE. Look around.

The Sins of the Fathers.... yadayadayadda

Lots of pieces to this puzzled thread... to be discussed further over chamomile.

RC