Over several days of questioning in 2008, the detainee provided precise directions on how to find the secret headquarters for the insurgent group's media wing, down to the color of the front door and the times of days when the office would be occupied. When asked about the group's No. 2 leader — a Moroccan-born Swede named Abu Qaswarah — he drew maps of the man's compound and gave up the name of Qaswarah's personal courier.

Weeks after those revelations, U.S. soldiers killed Qaswarah in a raid in the Iraqi city of Mosul. Meanwhile, the detainee, U.S. officials say, would go on to become famous under a different name: Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi — the current leader of the Islamic State.

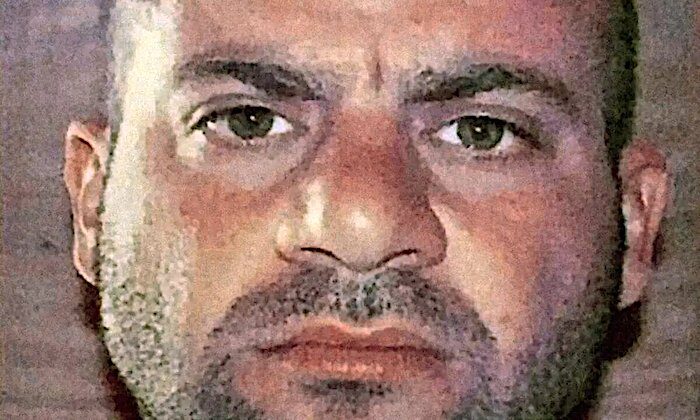

U.S. officials opened a rare window into the terrorist chief's early background as a militant with the release this week of dozens of formerly classified interrogation reports from his months in an American detention camp in Iraq. Whereas the Defense Department previously released a handful of documents that cast the future Islamic State leader as an informant, the newly released records are an intimate portrait of a prolific — at times eager — prison snitch who offered U.S. forces scores of priceless details that helped them battle the terrorist organization he now heads. The Islamic State grew out of an organization that was once called al-Qaida in Iraq.

"Detainee seems to be more cooperative with every session," one 2008 report says of the man whose real name is Amir Muhammad Sa'id Abd-al-Rahman al-Mawla. "Detainee is providing a lot of information on ISI associates," says another.

As spelled out over 53 partially redacted reports, Mawla's cooperation with American forces included assisting with artists' sketches of top terrorism suspects, and identifying restaurants and cafes where his erstwhile comrades preferred to dine.

In an ironic twist, Mawla appears in the reports to be particularly helpful in equipping the Americans to go after the group's propaganda unit, as well as non-Iraqis in his organization — volunteers from across the Middle East and North Africa who joined the group during the U.S. occupation of Iraq. Foreign terrorism branches and media operations are regarded as the most effective components of today's Islamic State.

Christopher Maier, director of the Defense Department's Defeat-ISIS Task Force, who discussed in an interview the records released by the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, a Pentagon-funded academic institution at the U.S. Military Academy, said:

"He did a number of things to save his own neck, and he had a long record of being hostile — including during interrogation — toward foreigners in ISIS. With the rise of ISIS, and the desire to form a caliphate with thousands of foreign fighters, that's problematic for Mawla."The records, which were released as part of an academic study, have helped U.S. officials fill in blanks in the biography Mawla, a relatively obscure functionary in the Islamic State when he was named as the caliph after the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in October 2019. After some initial uncertainty about the true identity of the new leader, U.S. counterterrorism officials concluded that it was Mawla, an Iraqi figure well known to them from his previous captivity.

The Iraqi, then a 31-year-old midlevel official within the Islamic State of Iraq - later known simply as the Islamic State — was apparently captured in late 2007 or early 2008, and was subjected to dozens of interrogations by U.S. military officials. The precise date of his release is not known, but the interrogation record stops in July 2008. By then, al-Mawla has stopped being cooperative, and reports reveal that he was "anxious" about his status, suggesting that he expected to be rewarded for the quantity of information he supplied.

What is clear from the reports is that over a period of at least two months in early 2008, Mawla was an interrogator's dream, revealing the identities of terrorism leaders and providing map-like directions on how to find them. In one instance, he walked U.S. officials through his personal phone book, a black notebook that was seized when he was captured. In one session, he pointed out the phone numbers of 19 Islamic State officials and even disclosed how much money some of them made.

"Al-Mawla was a songbird of unique talent and ability," Daniel Milton, an associate professor at the Combating Terrorism Center and one of the researchers who reviewed the documents, wrote in an essay published by the national security blog Lawfare. "These [interrogation reports] are chock-full of such details."

The officials who released the documents clearly understood their potential as a source of embarrassment for Mawla, although the Islamic State leader's background as an informant was already known within Islamist militant circles. Prominent commentators on pro-Islamic State social media sites criticized the decision to elevate the Iraqi to caliph, arguing that he was not qualified for the job.

He took the position several months after the liberation of the last of the Islamic State's territorial holdings in Syria, and since that time he has kept a relatively low profile. U.S. counterterrorism officials think he is hiding out in Iraq or Syria, the terrorist group's traditional base. There, he has continued to wage a low-grade insurgency marked by frequent attacks against military outposts and government and tribal officials.

The group's propaganda organs meanwhile have sought to shift attention to the achievements of Islamic State branches in Africa, where well-armed terrorists are regularly killing government soldiers and occasionally seizing territory. Last month, militants seized the town of Palma on Mozambique's northern coast in a brazen operation that killed dozens.

U.S. officials warn that even a tarnished and partially defanged Mawla remains dangerous, given the ample opportunities to acquire money, weapons and recruits in ruined and largely lawless provinces in eastern Syria.

John Godfrey, the State Department's acting special envoy for the global coalition against the Islamic State, said:

"They're biding their time and waiting for circumstances to change in their favor. They're conducting just enough high-profile attacks to show that they're still there and still relevant."

Comment: See also: Dead or alive? Washington ups bounty to $10M on Daesh leader Mawla