First, it was the Security Service, MI5; then the Secret Intelligence Service, MI6; now GCHQ has approved an authorised history.

GCHQ was the most secretive of Britain's security and intelligence agencies. Its eye-catching modern headquarters, widely referred to as "the doughnut", is now the best-known building in Cheltenham, a spa town in southwest England.

GCHQ has more than 7,000 staff - many of them computer wizards, mathematicians and linguists - excluding Royal Air Force, Navy and Army signals experts working with the agency. It takes up the lion's share of Britain's £3-billion plus secret intelligence budget.

The initials GCHQ, which not so long ago could only be whispered, are prominently displayed on local bus routes. GCHQ's books of puzzles are popular Christmas gifts.

"Behind the Enigma" is the clever but misleading title of the spy agency's authorised history. Over more than 600 pages, its author, Canadian historian John Ferris, ignores or simply dismisses GCHQ's most controversial activities - notably, the bulk interception of private communications without proper safeguards - as "scandals". It is a description he uses to suggest that concerns about what GCHQ has been up to are exaggerated.

Successive British governments, egged on by the security and intelligence establishment, have accused "left-wingers" and assorted "subversives", including journalists and whistle-blowers, of sabotaging Britain's "national security" by investigating what the spooks - in MI5 and MI6 as well as GCHQ - are doing.

Yet Ferris also suggests that GCHQ has long wanted to be more open, blaming excessive secrecy on Whitehall mandarins. Seizing every opportunity to place GCHQ in a good light, he says the agency began to realise that less secrecy has actually helped GCHQ by allowing it to be trusted more and improve its image. Thus the author claims:

"Whitehall and its opponents drove Britain down a road of scandal, which ultimately made GCHQ a public and trusted institution. Scandals stemmed simply from reporting basic facts, which often were innocuous. Accounts of GCHQ's successes could not be reported. GCHQ could not defend itself publicly against attacks."Prime suspect

Pursuing his tricky path, Ferris includes in his account of what he calls "several scandals" the notorious ABC official secrets case, named after the surname initials of the three defendants.

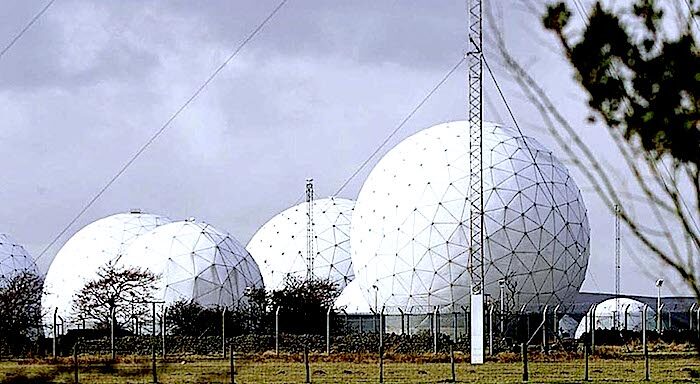

The journalists Crispin Aubrey and Duncan Campbell, and army signals corporal John Berry, were arrested after Time Out magazine in 1976 published "The Eavesdroppers", an article that blew GCHQ's cover, revealing its hitherto secret activities and its close ties to the American National Security Agency's (NSA) huge base at Menwith Hill in North Yorkshire.

Senior GCHQ officials were shocked. Ferris, however, blames what he calls the "heavy handed" decision to prosecute the three men on "Whitehall" rather than GCHQ.

Ferris refers very briefly to the Geoffrey Prime case that led to GCHQ's first official "avowal" - acceptance of its role as a spy agency - in 1982. Prime, a former GCHQ officer, was arrested on suspicion of molesting young girls. It was only after his wife found spying equipment under the floorboards of his house that he was arrested for espionage.

He was sentenced to 38 years in jail - 35 for selling secrets, three for sex offences against children. Ferris notes that the Security Commission (a body that no longer exists, but which investigated security lapses) publicly condemned GCHQ over the Prime case.

Yet, as though embarrassed at having to mention the Prime case at all, Ferris in the very same paragraph quickly adds: "Simultaneously, the quality newspapers... published material which threatened security and victory during the Falklands conflict" of 1982.

Trumpeting GCHQ successes whenever possible, he describes at length how the agency provided intelligence to British forces throughout the Falklands war. This included information that the Argentine cruiser, the Belgrano, was about to be involved in a pincer movement against British warships when it was sunk by the submarine, HMS Conqueror, with the loss of 323 lives.

Yet again GCHQ is let off the hook. Its role had to be kept secret. In a curious - indeed, enigmatic - comment, Ferris observes: "Any British response to danger must seem bad when based on intelligence it could not report without losing the source."

Ferris continues on his meandering journey, not quite knowing how to marry his criticism of whistle-blowers and journalists with his claim that GCHQ wanted all along to be more open but was prevented from doing so by the mandarins of Whitehall.

Revealing Zircon

In a further case, he goes on to blame anonymous forces (presumably those same mandarins) for overreacting by threatening in 1986 to prosecute journalists who disclosed plans to build Britain's first signals intelligence satellite, codenamed Zircon.

Yet it was Peter Marychurch, GCHQ director at the time, who pressed for a court injunction to stop journalists and the BBC from revealing the Zircon plan.

The reason, Marychurch explained - in a court document Ferris does not mention - was that the Zircon disclosure

"could cause the US to lose confidence in the United Kingdom's ability to protect the highly classified information involved and to reduce or withdraw their cooperation (which is essential to the UK) in this and related fields of great importance to the country's security".It soon emerged that the Treasury strongly opposed the project because of its cost. Zircon was cancelled.

Ferris ends his brief comment on that episode by making the dubious and rather sinister claim that "only the chattering classes cared about scandals over Sigint [signals intelligence], and then not much". He continues what has now become a well-worn theme:

"GCHQ moved suddenly from anonymity to becoming a favourite target for suspicion on the left of British politics and the media. GCHQ did not intend to have its current activities made as public as they are in 2020."The agency may have wanted to be more open to gain more trust but Ferris comments with no hint of irony.

The author makes just a passing reference to an unprecedented crisis in US-UK relations involving GCHQ. This occurred in 1973 when Henry Kissinger, president Richard Nixon's national security adviser - who was angry about prime minister Edward Heath's habit of consulting European allies rather than the US on major policy matters - cut off intelligence cooperation between the two countries.

I feel personally vindicated by one passage in the book. Sir Brian Tovey, the former GCHQ director, sought an apology from me when I suggested that pressure from the US contributed to Margaret Thatcher's decision in 1984 to ban trade union membership for staff at the agency. The US had nothing to do it with it, he insisted.

Ferris lets the cat out of the bag. He describes how, when the then NSA director, Admiral Bobby Inman, learned of the decision to ban unions at GCHQ, Inman replied: "That's marvellous". Tovey had raised the plan "through private discussions" with NSA directors, something, as Ferris puts it, that "eliminates an important part of the record".

Geoffrey Howe, foreign secretary at the time, implied in the House of Commons that industrial action by union members at GCHQ threatened national security during the Falklands crisis. His claims were misleading, as Ferris makes clear.

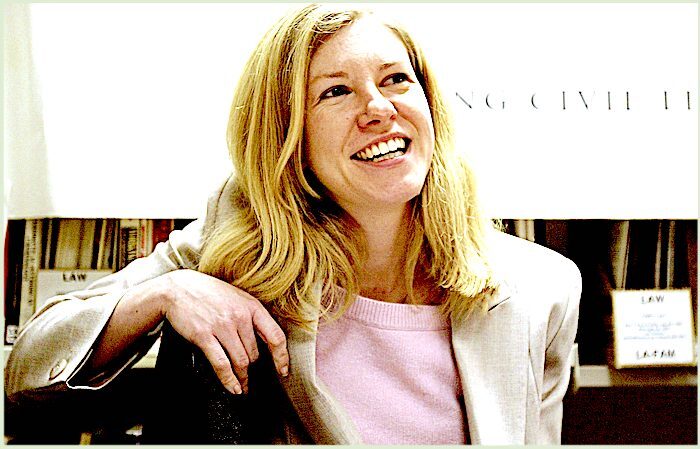

Ferris offers a fleeting reference to Katharine Gun - the young GCHQ translator who blew the whistle on the NSA's instruction to GCHQ to bug the UN offices and the homes of diplomats from those countries concerned about the US-led invasion of Iraq, the subject of the film Official Secrets. Curiously, he suggests that her leak proved that GCHQ's success in intercepting communications had "reached the highest levels in history, providing much first-rate material on first-rate issues".

He does not say why Gun decided to blow the whistle or why the government abandoned her prosecution. I was told by impeccable sources that GCHQ's own lawyers privately warned the government there was a strong case for arguing that the planned invasion would be unlawful.

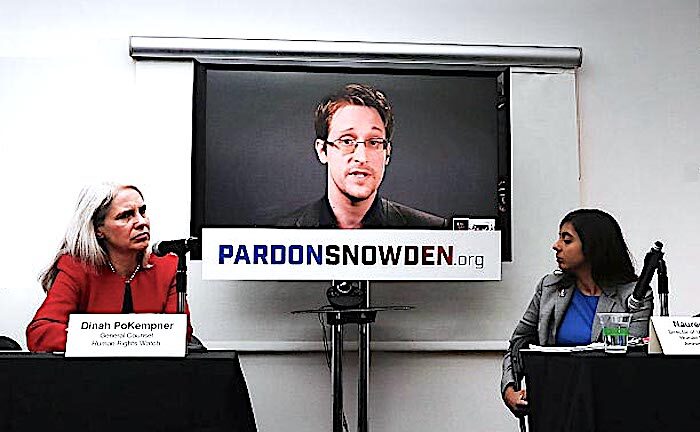

Even more strangely, Ferris says that GCHQ's "first-rate" success in intercepting communications was also demonstrated by the disclosures in 2013 to The Guardian and US newspapers by the NSA contractor, Edward Snowden.

Snowden, widely branded a traitor in Britain and the US, revealed how for years GCHQ and the NSA were involved in the mass interception of private communications, sometimes with the help of large private companies and without any independent oversight.

Snowden revealed that by 2012, GCHQ was handling 600 million telephone calls a day, tapping more than 200 cables.

Ferris notes that Snowden's revelations led to David Anderson, the government's independent reviewer of terrorism laws, to propose stricter control of GCHQ "with much more oversight". Yet he claims that the "technicalities involved" in Snowden's disclosures, "and the constant drip of information, confused and bored the public". I wonder what evidence he has for that claim.

In 2018, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that GCHQ's bulk interception of online communications violated privacy and failed to provide sufficient surveillance safeguards. No mention of that.

I could go on, so inadequate and one-sided, sometimes contradictory and often puzzling, is this account of Britain's biggest and most powerful intelligence-gathering agency.

For years it lived under the shadow of the wartime successes - brilliant, but whose impact has been exaggerated - of its predecessor, the government's code & cypher school at Bletchley, famous for cracking the German Enigma code.

"Bletchley matters too much for history to be understood through myth," writes Ferris. Yet so does GCHQ, now and in the future.

About the author

Richard Norton-Taylor was The Guardian's defence correspondent and its security editor for three decades and is the author of several books, most recently The State of Secrecy.

Reader Comments

R.C.