A recent report from the Potsdam Institute predicts that by 2050 there will be four billion overweight people in the world, with one-and-a-half billion of them obese. This is not entirely surprising. The world has been getting fatter for years, and things do not seem to be slowing down.

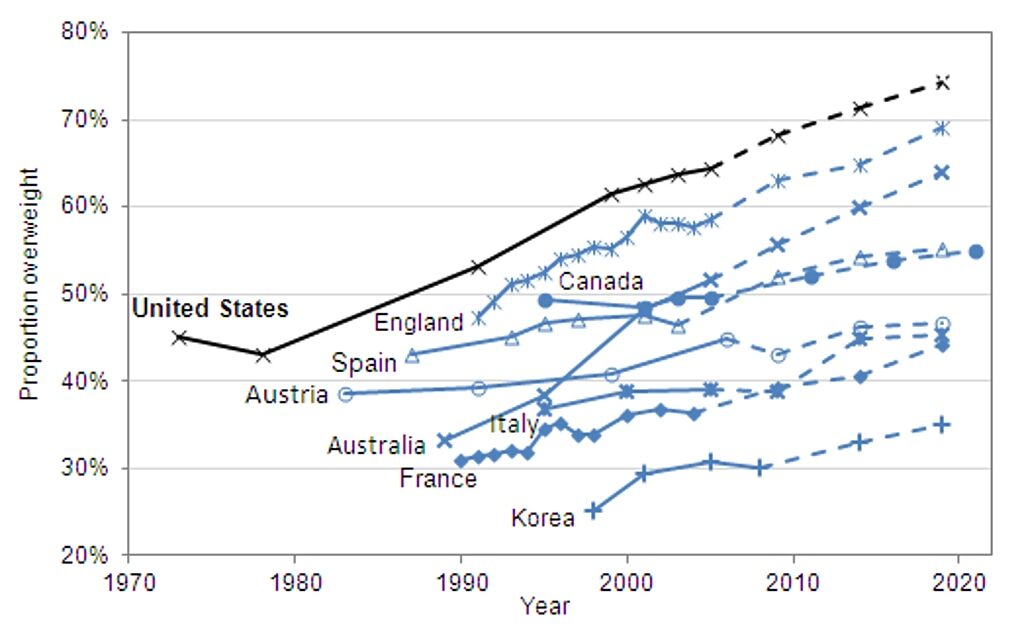

This Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) graph, which looks at the rise in overweight adults in a number of different countries, shows that the trend seems inexorably upward.

Why is this happening? There are undoubtedly a number of factors at play here. Socio-economic status plays a significant part in many countries. Those with poorer educational attainment are more likely to be overweight, an association that is much stronger in women than men, for reasons that are not clear.

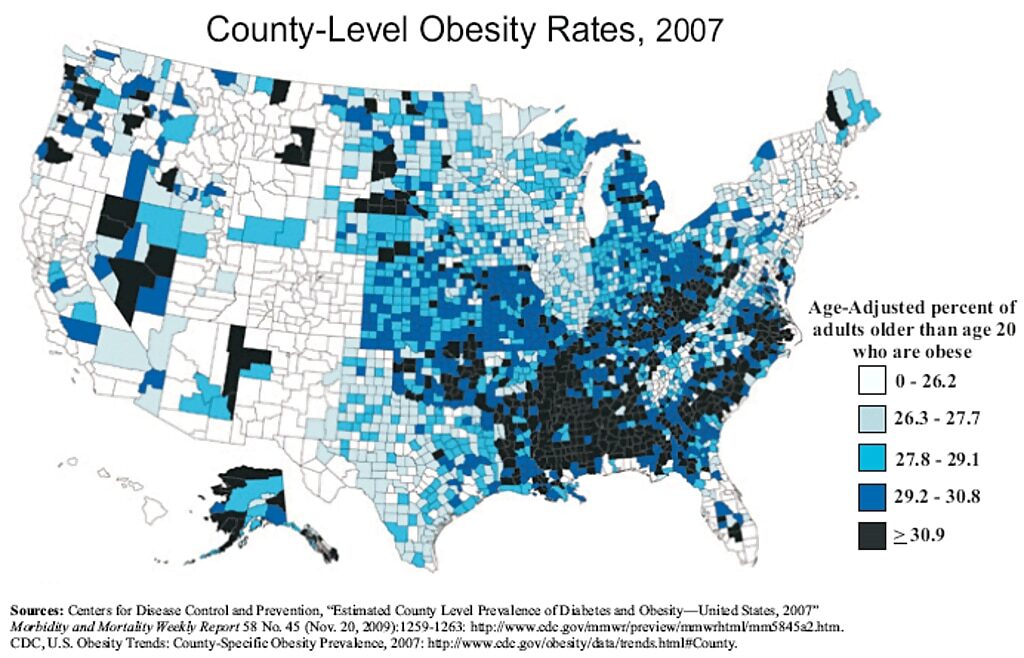

It is also fascinating to look at where obesity levels are highest in the US, essentially in the poorer southern States.

When you analyse the data, it is clear that obesity is not evenly distributed and there is a very clear difference between rich and poor. Why? That is probably beyond the scope of this article. Instead I am going to consider something else that I think is having a significant impact: dietary guidelines.

At one time, there was no such thing as a dietary guideline. The first was one was published in 1976, in the US. The UK followed suit, then much of the rest of the world. Before this, people ate pretty much whatever they wanted. Imagine that! There was no one to tell you what you should, or should not, eat. How on Earth did they survive?

The guidelines were not developed in an attempt to reduce the rates of obesity, which was not considered a major problem at the time. They were designed to protect against heart disease, which was the major killer. It still is, although the rates have fallen. The guidelines themselves promoted a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet.

Prior to 1976, there was not really a major problem with weight or obesity in the US. Then came the guidelines, and from that point onwards, things changed, as the rising obesity levels in the US demonstrated.

In the UK, there were no dietary guidelines until 1980, at which point exactly the same upturn in obesity occurred as was seen in the US. There was an immediate uptick, then an unstoppable rise.

As an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) noted,

"Beginning in the 1970s, the US government and major professional nutrition organizations recommended that individuals in the United States eat a low-fat/high-carbohydrate diet, launching arguably the largest public health experiment in history. Throughout the ensuing 40 years, the prevalence of obesity and diabetes increased several-fold, even as the proportion of fat in the US diet decreased by 25 percent."The article went on to say that "a comprehensive examination of this massive public health failure has not been conducted."

Has this been a case of cause and effect? One GP in the UK, Dr. David Unwin, has done a great deal of research in this area. He has managed to reverse type-2 diabetes in very nearly 50 percent of his patients by putting them on a diet which is the exact opposite of that promoted by the dietary guidelines. It is high in fat, and low on carbohydrates. Not only did he reverse diabetes, he also achieved significant and long-lasting weight loss.

A report on his findings stated:

"It was observed that a low carbohydrate diet achieved substantial weight loss in all patients and brought about normalization of blood glucose control in 16 out of 18 patients."In a more recent and bigger study on nearly 200 patients, he achieved a combined weight loss of 1.9 metric tons (1,900kg) in weight.

There are reasons why a diet high in carbohydrates - sugar, bread, pasta, soft sugary drinks, crisps, chips and suchlike - can drive weight gain. These reasons are based on the fact that carbohydrate consumption drives insulin release. This, in turn, promotes energy storage, and traps energy in fat cells.

The higher insulin then causes blood sugar levels to fall, driving hunger, leading to more food consumption. So, people become trapped in a cycle of eating and hunger. It has to be acknowledged, though, that there is heated medical debate in this area, to put it mildly.

However, in my opinion, the evidence is pretty overwhelming. The levels of overweightness and obesity remained pretty much flat for decades. Then, along came the dietary guidelines promoting low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets. And at that point, problems with obesity and type-2 diabetes took off, firstly in the US and then the rest of the world.

Researchers such as Dr. David Unwin, who have been brave enough to push back against the guidelines, have had spectacular results by changing the diet to high-fat, low-carb. Time for a major rethink, in my opinion.

Malcolm Kendrick, doctor and author who works as a GP in the National Health Service in England. His blog can be read here and his book, Doctoring Data - How to Sort Out Medical Advice from Medical Nonsense, is available here.

Comment: