More than three hundred years after Antonie van Leeuwenhoek used one of the earliest microscopes to describe human sperm as having a "tail, which, when swimming, lashes with a snakelike movement, like eels in water", scientists have revealed this is an optical illusion.

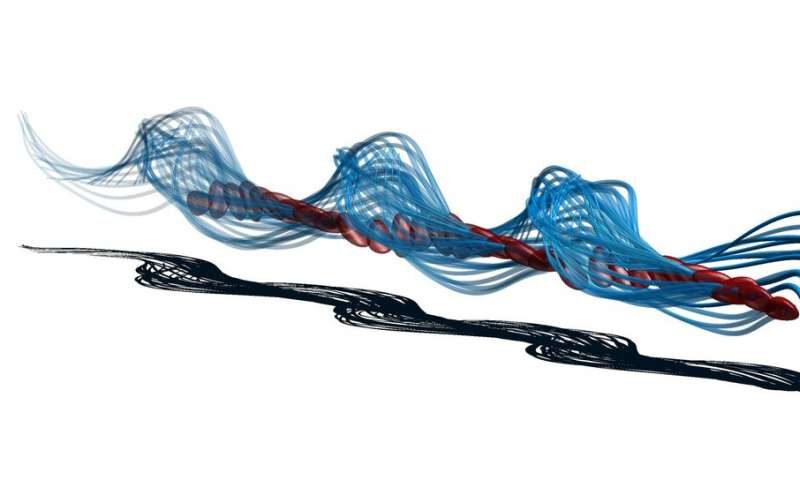

Using state-of-the-art 3-D microscopy and mathematics, Dr. Hermes Gadelha from the University of Bristol, Dr. Gabriel Corkidi and Dr. Alberto Darszon from the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, have pioneered the reconstruction of the true movement of the sperm tail in 3-D.

Using a high-speed camera capable of recording over 55,000 frames in one second, and a microscope stage with a piezoelectric device to move the sample up and down at an incredibly high rate, they were able to scan the sperm swimming freely in 3-D.

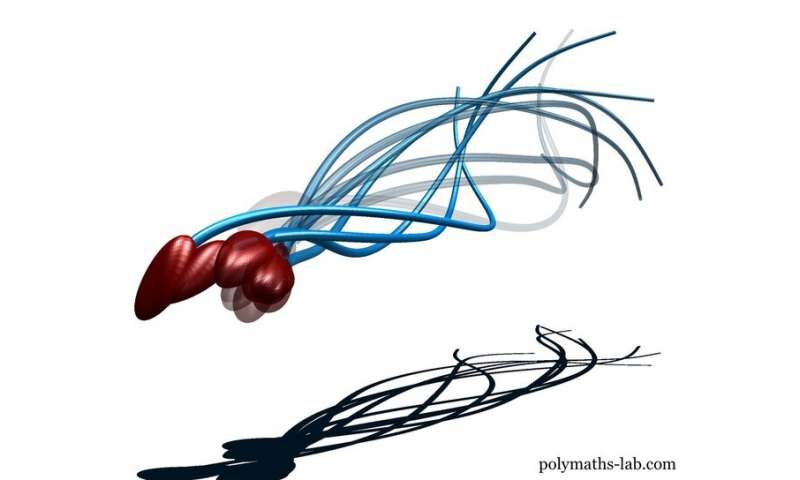

The ground-breaking study, published in the journal Science Advances, reveals the sperm tail is in fact wonky and only wiggles on one side. While this should mean the sperm's one-sided stroke would have it swimming in circles, sperm have found a clever way to adapt and swim forwards.

"Human sperm figured out if they roll as they swim, much like playful otters corkscrewing through water, their one-sided stoke would average itself out, and they would swim forwards," said Dr. Gadelha, head of the Polymaths Laboratory at Bristol's Department of Engineering Mathematics and an expert in the mathematics of fertility.

"The sperms' rapid and highly synchronized spinning causes an illusion when seen from above with 2-D microscopes — the tail appears to have a side-to-side symmetric movement, "like eels in water", as described by Leeuwenhoek in the 17th century.

"However, our discovery shows sperm have developed a swimming technique to compensate for their lop-sidedness and in doing so have ingeniously solved a mathematical puzzle at a microscopic scale: by creating symmetry out of asymmetry," said Dr. Gadelha.

"The otter-like spinning of human sperm is however complex: the sperm head spins at the same time that the sperm tail rotates around the swimming direction. This is known in physics as precession, much like when the orbits of Earth and Mars precess around the sun."

Computer-assisted semen analysis systems in use today, both in clinics and for research, still use 2-D views to look at sperm movement. Therefore, like Leeuwenhoek's first microscope, they are still prone to this illusion of symmetry while assessing semen quality. This discovery, with its novel use of 3-D microscope technology combined with mathematics, may provide fresh hope for unlocking the secrets of human reproduction.

Dr. Corkidi and Dr. Darszon pioneered the 3-D microscopy for sperm swimming.

"This was an incredible surprise, and we believe our state-of the-art 3-D microscope will unveil many more hidden secrets in nature. One day this technology will become available to clinical centers," said Dr. Corkidi.

"This discovery will revolutionize our understanding of sperm motility and its impact on natural fertilization. So little is known about the intricate environment inside the female reproductive tract and how sperm swimming impinge on fertilization. These new tools open our eyes to the amazing capabilities sperm have," said Dr. Darszon.

More information: "Human sperm uses asymmetric and anisotropic flagellar controls to regulate swimming symmetry and cell steering" Science Advances (2020).

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aba5168 Journal information: Science Advances

Comment: See also: Choosy eggs may pick sperm for their genes, defying Mendel's law