The findings come from Grotta dei Moscerini, a picturesque cave that sits just 10 feet above a beach in what is today the Latium region of central Italy.

In 1949, archaeologists working at the site dug up some unusual artifacts: dozens of seashells that Neanderthals had picked up, then shaped into sharp tools roughly 90,000 years ago.

Now, a team led by Paola Villa of the University of Colorado Boulder has uncovered new secrets from those decades-old discoveries. In research published today in the journal PLOS ONE, she and her colleagues report that the Neanderthals didn't just collect shells that were lying out on the beach. They may have actually held their breath and went diving for the perfect shells to meet their needs.

Villa, an adjoint curator in the CU Museum of Natural History, said the results show that Neanderthals may have had a much closer connection to the sea than many scientists thought.

"The fact they were exploiting marine resources was something that was known," Villa said. "But until recently, no one really paid much attention to it."

Cave discoveries

When archaeologists first found shell tools in Grotta dei Moscerini, it came as a surprise. While Neanderthals are well-known for crafting spear tips out of stone, few examples exist of them turning shells into tools.

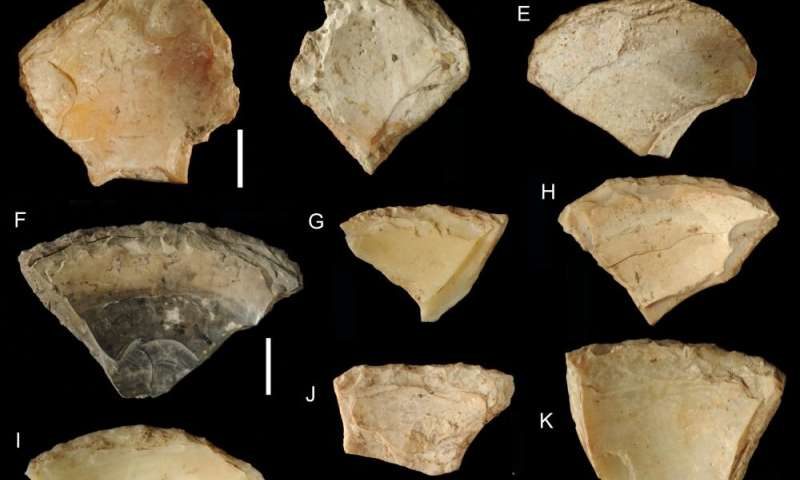

But the find wasn't a fluke. The 1949 excavation of the cave unearthed 171 such tools, all valves from shell belonging to a local species of mollusk called the smooth clam (Callista chione). Villa explained that the ancient humans used stone hammers to chip away at these shells, forming cutting edges that would have stayed thin and sharp for a long time.

"No matter how many times you retouch a clam shell, its cutting edge will remain very thin and sharp," she said.

But did the Neanderthals, like many beachgoers today, simply collect these shells while taking a stroll along the sand?

To find out, Villa and her colleagues took a closer look at those tools. In the process, they found something they weren't expecting. Nearly three-quarters of the Moscerini shell tools had opaque and slightly abraded exteriors, as if they had been sanded down over time. That's what you'd expect to see, Villa said, on shells that had washed up on a sandy beach.

The rest of the shells had a shiny, smooth exterior.

Those shells, which also tended to be a little bit bigger, had to have been plucked directly from the seafloor as live animals.

"It's quite possible that the Neanderthals were collecting shells as far down as 2 to 4 meters," Villa said. "Of course, they did not have scuba equipment."

Researchers also turned up a large number of pumice stones from the cave that Neanderthals had collected and may have used as abrading tools. The stones, Villa and her colleagues determined, washed onto the Moscerini beach from volcanic eruptions that occurred more than 40 miles to the south.

Going for a dip

She's not alone in painting a picture of beach-loving Neanderthals.

In an earlier study, for example, a team led by anthropologist Erik Trinkaus identified bony growths on the ears of a few Neanderthal skeletons. These features, called "swimmer's ear," can be found in people who practice aquatic sports today.

For Villa, the findings are yet more proof that Neanderthals were just as flexible and creative as their human relatives when it came to eking out a living — a strong contrast to their representation in popular culture as a crude cavemen who lived by hunting or scavenging mammoths.

"People are beginning to understand that Neanderthals didn't just hunt large mammals," Villa said. "They also did things like freshwater fishing and even skin diving."

Other coauthors on the new study included researchers from the French National Centre for Scientific Research, the University of Geneva, Roma Tre University, Sapienza University of Rome and the University of Pisa.

Comment: See also: