Authored by Michael Wilson, Morgan Stanley chief equity strategistDeja Vu

As we head toward the end of the third quarter, I can't help but think it feels very similar to last year in many ways. The S&P 500 is near its all-time high at 3000, while the MSCI EM Index and the Topix sit 20% and 15% below their highs and the Eurostoxx is 7% lower, leaving all these indices exactly where they traded a year ago. Growth stocks are still the most crowded part of equity managers' portfolios - and the love affair may be stronger than ever at this point. But there are important differences too. Cyclical stocks have completely fallen out of bed and trade 20% lower than last September, while long-duration sovereign debt has been the best investment by far over this period, with 10-year Treasury yields 50% lower than just 12 months ago. To put this into context, over the past 50 years such a dramatic move in yields over the prior 12 months has only happened twice - during the global financial crisis in 2008 and the European sovereign debt crisis of 2011-12.

With many citing new highs for the S&P 500 as evidence of a resurgent bull market, something seems amiss. A well-balanced global equity portfolio has made little progress over the past year and is actually down over the past 20 months. Sure, growth and defensive stocks have done well but neither has bested a risk-free portfolio of long-duration Treasuries, which leads me to my next point. In the past year, defensive stocks and bonds have been the place to be, not growth stocks, particularly on a risk-adjusted basis. While growth stocks resumed their leadership during the first half of the year, they relinquished it again in mid-July, which is when the positive correlation between bonds and stocks reversed. That was right before the Fed began cutting interest rates and jibes with my view that a Fed pause is good for stocks, but Fed cuts, if they're the start of a full-blown rate-cutting cycle, are bad.

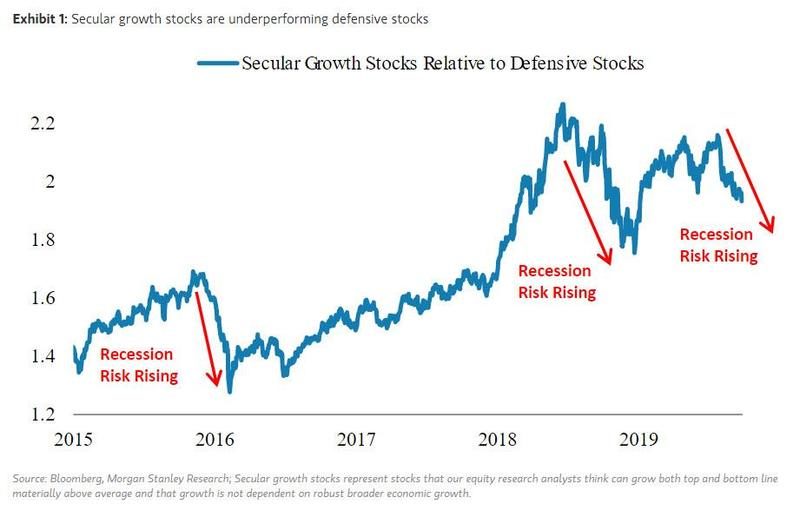

My view remains that the risk in Fed scenarios is weighted towards significantly more cuts because growth is slowing much more than many seem willing to acknowledge, and the risk of a recession has increased materially. As noted above, an equity manager has made money over the past year in just two types of stocks - growth or defensively oriented ones. In July, that began to change, and we have been recommending a long defensive/short secular growth pair as a way to capture what could be the next move in this cyclical bear market - pricing a recession whether we have one or not. In short, we're moving from the perception that this is late-cycle to a belief that it's end of cycle. When that shift occurs, defensive stocks outperform secular growth stocks (Exhibit 1).

Indeed, that's precisely what has been happening since July, first during the growth scare in August and then further in the momentum reversal in early September. During the most recent growth scares in late 2015/early 2016 and 4Q18, the defensive cohort outperformed secular growth by 25%. So far, the outperformance has been around 12%, or about half of what I expect to see before it's over.

In addition to the material increase in US recession risk, one more thing has changed from last year that's worth considering. The recent failure of We Company to go public is reminiscent of past corporate events marking important tops in powerful secular trends:

- United Airlines' failed LBO in October 1989, which effectively ended the high yield/LBO craze of the 1980s.

- The AOL/TWX merger in January 2000, bringing the Dotcom bubble to a close.

- JPM's take-under of Bear Stearns in March 2008, which signaled the end of the financial excesses of the 2000s.

I initially read this as "'Something's amiss': Risk of recession increasing, markets similar to the last years before the collapse - Morgan Stanley"

By collapse I assumed the great depression.

It's all paper no matter the interpretation. My headline may be the right one.