© Ancient Origins

The great issue facing the binary theory today is, well, the absence of an obvious candidate for the part. In the visible realm, we do not appear to have any stars near enough that fit the bill, according to our current understanding of physics (Newton's Laws place physical restrictions on distance calculations).

Although it's a long shot, the existence of a visible companion to our Sun could still be possible under circumstances we will investigate later.We have seen that the idea of a binary, while controversial, is not a new one. References to it in ancient writings and belief systems are there, though largely ignored by researchers and historians. With the majority of stars in the universe (all 1 % of it) being attached to binary or multiple star systems, the obvious question is, why wouldn't

our own Sun have a partner star as well? Statistically, it's not at all likely that our Sun would be a loner. To many astronomers, though, the binary idea is an annoyance that just won't die. They may ignore or disagree with the theory, but at the same time can't disprove it.

Comet Impacts and Mass ExtinctionsThe history of the modern binary search begins in the early 1980s with Nemesis. At the time, paleological data seemed to indicate a trend of cyclical extinction patterns in the Earth's strata, roughly showing

a mass extinction about once every 26 million years. As scientists searched for answers, two separate teams, one at the University of Louisiana, and the other at UC Berkeley, presented an intriguing theory - and the idea of "

Nemesis" arose. The Nemesis theory proposed that the mass extinctions were caused by

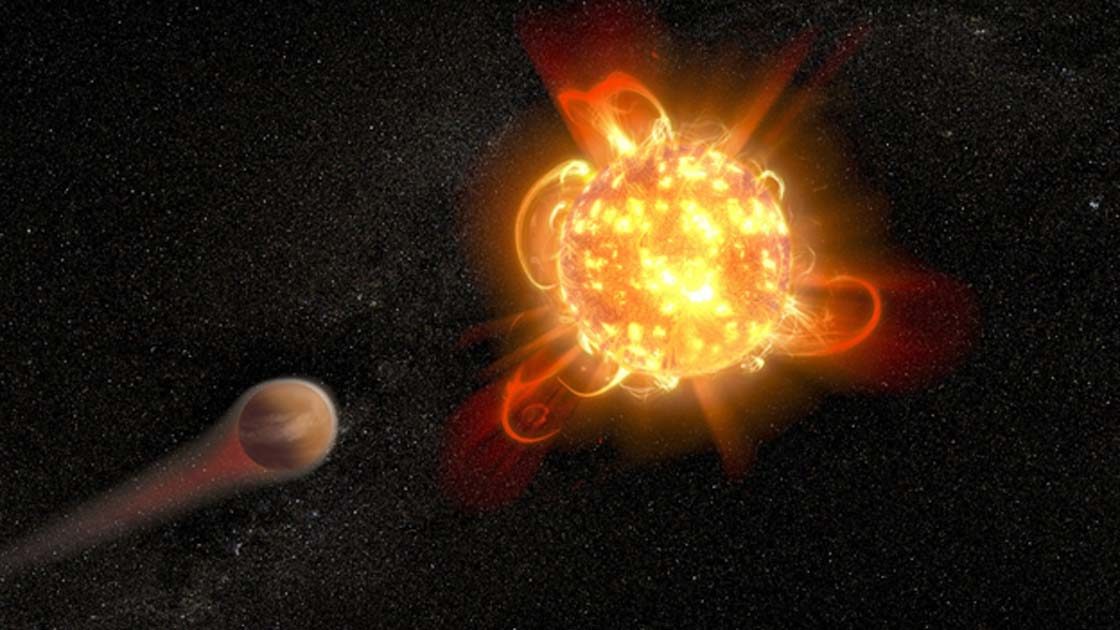

comet impacts and that they occurred on a regular basis because there was some large mass object, dubbed the Nemesis Star, in a binary orbit with our Sun. In that hypothesis, every 26 million years or so Nemesis would get close enough to the Sun to stir up comets in the Oort Cloud, a vast debris field thought to contain trillions of comets, stretching a thousand times farther than Pluto. This disturbance would send a large number of comets towards the inner solar system, significantly increasing the chances of an impact with Earth.

It was a very sexy theory that received large amounts of media attention and forced the scientific community to address the issue. Some found merit in the theory, while others picked at its flaws. One of the issues dogging the hypothesis was that the two teams of scientists could not agree on what the object was - even though they agreed on the term of periodicity for the mass extinctions (26 million years). Professor Richard Muller at Berkeley believed it was likely a dim Red Dwarf that had yet to be detected. Professors Dan Whitmire and John Matese, physicists with the University of Louisiana, leaned toward the possibility that it was a Brown Dwarf - basically a large mass object that is not quite big enough to sustain fusion and become a full-fledged star. While some contested the paleological evidence, they could not disprove the theory on this issue alone. In turn, many astronomers looked to IRAS, the Infrared Astronomical Satellite, and the results of its All Sky Survey to either confirm or disprove the Nemesis theory.

Read the the rest of the article

Another fairy tale to keep our vibrational state low from constant fear.

Why is theory held as fact so readily these days ?

An unexciting truth may be eclipsed by a thrilling lie. - Aldous Huxley