The official explanation reads like a science-fiction novel: a cloud of plasma ejected from the Sun collided with and compressed Earth's magnetic field, causing the spontaneous explosions.

A recent research paper has reconfirmed the long-held suspicions that space weather was to blame.

And according to Dr Richard Marshall from the Bureau of Meteorology's space weather team, who wasn't part of the study, the results are far from fictional.

So how does space weather work and what are the potential consequences for our increasingly tech-dependent world?

Dr Marshall says the Vietnam incident wasn't the first time space weather impacted Earth and it won't be the last.

The benchmark for an extreme space weather incident is the Carrington Event of 1859, when British astronomer Richard Carrington noticed a spectacular flash while observing the Sun.

Within the day the telegraph lines went berserk - the charge in the wires built up electrical potential to the point they arced and caused telegraph paper to catch fire.

There were also reports of auroras being observed in the tropics.

This was only one of many space weather events to impact Earth; some since we've been able to identify and there were likely many before.

Dr Marshall says major space weather events typically originate from "active regions" on the Sun where there are lots of sunspots.

Sunspots existed well before they were first observed telescopically in the 1600s, so it's a matter of when, not if, the next Carrington-scale event impacts Earth.

What causes these events?

Like a spitting pot of soup on the stove, the Sun is not a static solid.

"Bits of the Sun rotate at different speeds, twisting up the Sun's magnetic field lines, and as they get twisted up the stresses become too great and they eventually erupt." Dr Marshall said.

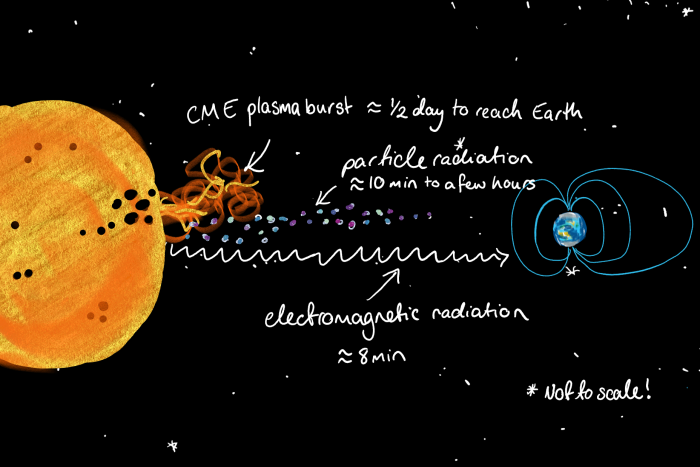

He says there are three main ejections from a solar flare that can impact Earth.

1. Electromagnetic radiation

The first and quickest form to reach Earth is electromagnetic radiation, the form of radiation that we see as light when it's in the right frequency.

Solar flares give off various frequencies of electromagnetic radiation but the intensity of a flare is measured in the X-ray emissions.

This burst of X-ray light races towards Earth at the speed of, well, light, taking approximately eight minutes to reach us.

Electromagnetic radiation can interfere with GPS systems, radars and can also cause HF radio blackouts.

2. Coronal mass ejections

Perhaps the most spectacular form of ejection from a solar flare is what is known as a coronal mass ejection (CME), which is a cloud of plasma that's sent hurtling through space.

Again, this is not a Star Trek script, it is very real. This plasma cloud takes longer to reach Earth - from half a day to a few days - but its impacts are phenomenal.

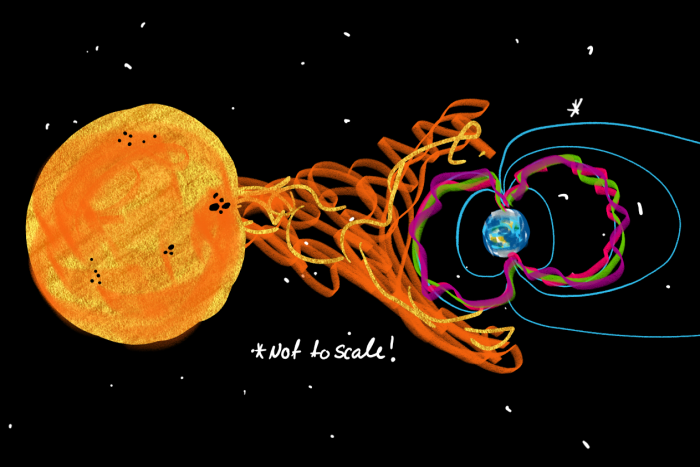

Dr Marshall says because the plasma clouds are carrying magnetic fields, they can couple with Earth's magnetic field.

When the plasma cloud arrives there are lots of currents flowing around Earth in a "magnetic storm".

He says the fields associated with these currents eventually make their way down and affect infrastructure like power grids and long pipelines.

A plasma cloud is what's believed to have coupled with Earth's magnetic field to set off those mines in Vietnam.

Plasma clouds also give us the auroras, and their impacts can be felt for up to 72 hours, Dr Marshall says.

3. Particle radiation

In big events, as plasma clouds accelerate through space they give energy to the particles around them, generating particle radiation.

It consists of little fast-moving particles that have both energy and mass, and takes between 10 minutes and several hours to reach Earth.

"Particle radiation can impact on satellites and aviation, as it increases radiation at aviation altitudes," Dr Marshall said.

What would happen today?

Recent studies suggest the chances of another Carrington-level event in the next 10 years are 3 per cent or 10.3 per cent, depending upon the method of calculation.

When you look back at how much havoc it caused to telegraph wires in 1859, it's pretty sobering for a modern technology-filled world.

There was a near miss in 2012 when a CME was flung out into space but luckily not towards Earth.

"I think [for our] modern technology, the biggest concerns are probably things like our reliance on GNSS, satellite-based positioning systems."

Going a day or two without maps on your phone might not be the end of the world, but think of the potential trouble for aviation or autonomous vehicles.

And while satellite infrastructure already operates in a hostile environment, space storms increase the danger and astronauts on the International Space Station will need to move into protected areas, he added.

But all is not lost. Dr Marshall says more and more nations are assessing the likely risk to their infrastructure, while the United Nations is trying to address the issue of extreme space weather from a global perspective.

The BOM's space weather team is also working with industry to try and reduce the impact of the next event.

"There's two options I guess. You go into these events doing nothing and being unaware, and then I think you really risk some perhaps quite serious consequences potentially," Dr Marshall said.

"Or you manage the events with your best estimates of what you should be doing in this situation with mitigating procedures that aim to minimise the impact to society. That's the plan."

At least someone has a plan.

Yep, it was the sun. Certainly not design flaws.