Erickson was the initiator of a nine-year series of meetings through the 1980s that came to be known as the Edinburgh Conversations. With the wholehearted support of the University's principal, Erickson created a 'back channel', away from politicking and press, which allowed Western and Soviet admirals and generals to engage face-to-face for open and mutually respectful dialogue in a neutral setting. According to parliamentarian Tam Dalyell, this initiative 'singlehandedly kept open contact with the Soviet high command and the Soviet military when times were at their most edgy.' Erickson himself ensured that the meetings - typically lasting about three days - were conducted strictly under 'academic rules'. (In Erickson's view, 'good scholarship is good morality.') This allowed them to proceed in good spirit, despite the tensions of the time. The series of Conversations continued for nine years, with the venue for annual meetings alternating between Edinburgh and Moscow.

Erickson's first encounter with the Russian army had been in Yugoslavia. He was serving there after the war had officially ended, and before his move into Intelligence, as a sergeant with the King's Own Scottish Borderers. One day the patrol he was commanding met a column of Soviet tanks, at which point the Russian commander stopped and challenged him. That challenge, so the story goes, was to a chess match, over tea. The anecdote has survived, I think, because it captures the enduring spirit of Erickson's engagement with the Russians, including at the highest levels.

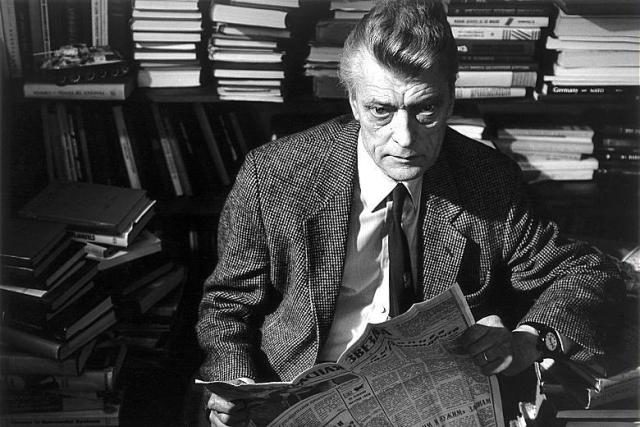

As one of very few academics to have the trust of both Americans and Soviets, he was able to mediate and contribute authoritatively, at the top table of military commanders. He was the West's leading authority on the Soviet military during and after the Second World War, as well as an expert on contemporary nuclear warfare defence grand strategy. He was an open consultant to NATO, the British Defence Ministry and the United Nations while his expertise on Soviet military history was admired by the Soviet leaders too. His two-volume work on Stalin's War with Germany was described by the historian Norman Stone as being 'as close to being the definitive work on Soviet strategy, and military history, as it is possible to imagine.' It 'was acclaimed not just in the West but also by Soviet generals (several of whom asked Erickson to autograph their copies)'. Tam Dalyell considered Erickson's 'supreme achievement was to make the Russians feel that their war effort and sacrifice was appreciated in the West.' He had 'shown to the full the achievement and heroism of the men and women who endured the fighting and who suffered on a scale almost inconceivable in the West.'

The Edinburgh Conversations ranged over complex discussions on arms control, related security issues and the environment. They afforded each side a valuable insight into each other's views, helped to thaw attitudes and influence official and academic thinking on both sides of the Cold War divide. The meetings continued from 1981 to 1989, at which point the two sides decided that relations between them had become good enough for state-to-state meetings to takeover from the academic ones.

In recognition of Erickson's achievement, Sir Michael Eliot Howard declared that 'Nobody deserves more credit for the ultimate dissolution of the misunderstandings that brought the Cold War to an end and enabled the peoples of Russia and their western neighbours to live in peace.'

It was above all about the peoples, and our prospects of living in peace, that Erickson ultimately most cared. Even as he attended to the details of both grand strategy and logistical specifics, he always retained clear awareness of the human dimension of decisions and their impacts. His approach to military history also had a strongly social dimension. His major work he described as 'an attempt to probe how the Soviet system functioned under conditions of maximum stress,' and he regarded it as 'a form of social history.' He reflected more generally, too, on the nature of the covenant between service people and the civil population of a country, finding significance in the extent of a citizenry's endorsement of military necessities.

I never really knew him personally. By the time I joined the Politics Department at Edinburgh he had already retired, and he would just come into his office from time to time while it still housed a part of his legendary library. (So substantial were his holdings, it turned out, that their weight had done structural damage to the building!) Those who knew him emphasised his strength of character and his humanity. The person who knew him best of all said that he had "tried desperately to keep peace between both sides. That was his mission in life."

Ljubica Petrovic met Erickson at Oxford. She was from Yugoslavia, a Serb, who, before being liberated by Russians, had witnessed the activities of the Croat extreme-right Ustashe. Her father, Dr Branko Petrovic, had fought in the Yugoslav Resistance, being captured and executed by the Germans in 1943. John and Ljubica married.

John Erickson's later years were marked by the bitter experience of witnessing the horror of NATO bombing Ljubica's country and relatives in the name of 'humanity'. In response, he did what he could - alongside the likes of Tam Dalyell, Tony Benn, John Pilger and Jeremy Corbyn - to bring to public attention the truth of what was happening in the Balkans, calling for more critical reporting of NATO's bombing and more coverage of the anti-war case in the media.

Comment: Readers might want to further read and view The Weight of Chains: US/NATO Destruction of Yugoslavia (Documentary).

The break up of Yugoslavia happened at a time before social media made possible even the modest degree of critical awareness now being achieved about media manipulations in relation to NATO activities. Even now, that briefly flourishing opportunity for critical understanding appears to be at risk of closing again as increasing restrictions are imposed on what can be heard in both mainstream media and social media. Meanwhile, a relentless propaganda message about 'evil Russians' is attaining acquiescence amongst a significant part of Western populations, even including some academics. So as belligerence is again being stoked between the West and Russia, we should really be looking to create the opportunities we can to resist this slide towards war.

My closing thought is that although Erickson's extraordinary combination of talents was of course unique, as was the historic opportunity into which he transformed the momentous challenge of his day, we can all learn something from the principles he applied in promoting real mutual understanding between Russia and the West. If there is one thing we can emulate it is his determination to participate in seeking ways to achieve peace. We can even try to seek out ways that others might not have thought of. A crucial requirement is not to be fooled by those who have an interest in promoting war. Among the key factors in Erickson's success at bringing together the great Cold War enemies was, I believe, his steadfast refusal to take nonsense from anyone. That was why he was trusted on both sides. Nor would he engage in any kind of subterfuge - notwithstanding the enticements that undoubtedly came his way. If the rest of us are not in a position get the top brass around a table as Erickson could, we can still engage in respectful and honest conversations with counterparts elsewhere in the world. We can build shared understandings, across contrived divides, of the simple truth that it is never we, the ordinary people, who seek war.

Notes

[1] What follows is excerpted from memories of friends and colleagues to be found in the following sources:

C.Raab et al, Fifty Years and More: The Department of Politics at the University of Edinburgh, University of Edinburgh 2012.

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2002/feb/12/guardianobituaries.humanities

https://www.nytimes.com/2002/03/19/world/john-erickson-72-dies-briton-chronicled-the-red-army.html

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1384537/Professor-John-Erickson.html

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2002/02/17/john-erickson-dies/6f2b5760-c163-4043-8c9f-17a8dfc039ce/?utm_term=.7bee4117946a

John Erickson: life and work (University of Edinburgh)

https://web.archive.org/web/20080611092508/http://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/professor-john-erickson-729741.html

Tam Dalyell, The Importance of Being Awkward, Edinburgh: Berlinn Ltd, 2012

Malcolm Mackintosh, 'John Erickson, 1929-2002', in P.J.Marshall (ed) Proceedings of the British Academy, Vol.124 (2005)

https://www.reddit.com/r/europe/comments/4vbc2j/kremlin_sows_discord_with_new_weapon_at_heart_of/

Only divine intervention (don't hold your breath-if you do you will only turn blue) can stop it now!