Robin was 13 when he found out he was adopted. Later he was told he had been abandoned - left in a box on London's Oxford Street. Now 74, he has spent most of his life wondering who left him and why. But thanks to DNA, and the dogged detective work of one of his daughters, he finally has some answers.

When Robin King discovered he was adopted he ran away from home. He had been snooping around his parents' bedroom when he came across his adoption papers in a holdall.

He fled to a friend's house and the pair then cycled from London to Southend where they slept in a tent until they were picked up by the police a few days later.

"My friend's mum had to pay for us to come back on the train," Robin recalls.

At home, no-one ever mentioned the subject of his adoption.

"I was afraid of raising it as I didn't want any confrontation. I think it affected me deep down," he says.

Robin had been adopted by Fred and Elsie King and grew up in a poor part of Woolwich, in south London. It was just after the end of World War Two and his earliest memories are of playing on bomb sites and his mother cleaning for the "rich people in Charlton".

He finished school with few qualifications and in his own words, "went off the rails for a while". But in his 20s he got married, had two daughters and moved to Peterborough, where he worked as a town planner, and later as an architect.

"I would never have got to where I did today without my family. I really love my two girls, they were the only people with a biological connection to me," he says.

A few years later Robin applied for a passport for work and was called by an official from the passport office. He had startling news.

"I was asked my age. Then the man said: 'I don't think it will bother you too much to learn that you were abandoned at the Peter Robinson store in London.'"

This was how Robin discovered that he was a foundling - and why his first name was Robin and his second was Peter.Many years passed before Robin next made serious efforts to discover more about his past. In 1996, already in his 50s, he went with his daughter Michaela to the London Metropolitan Archive to look at his full adoption record.

He learned he had been found outside the Oxford Circus department store on 20 October, 1943. It was a dangerous time to be in London. Although the Blitz had finished, there were still intermittent attacks by the Luftwaffe. Just 10 days earlier 30 tons of bombs had been dropped on the capital.

His file said he had been adopted by the Kings when he was four-and-a-half years old and that they had thanked the authorities for giving them such as "good little boy".

However, there were no clues as to why he'd been left. "Efforts to trace any relative of child have not been successful," one document stated.

Robin's daughter Lorraine decided to continue the search. Over the next 20 years she wrote to every TV show she could think of that reunited families or solved mysteries. Each time the reply was the same - without the names of the birth parents there was nothing to go on.

Lorraine then found a library archivist who searched through spools of microfilm looking for any mention of a foundling in old newspapers. She wrote to the Arcadia Group, which took over the Peter Robinson store, in case there was any mention in their archives.

"I used to have moments of inspiration when I thought, 'I know I'll write to so-and-so,'" Lorraine says.

Then last year she watched an episode of

The One Show on BBC One featuring a people-tracing expert called Cat Whiteaway.

"I contacted Cat explaining my dad's situation. A few weeks later she told me she had met someone she thought could help - a DNA detective called Julia Bell."

Julia had managed to track down her own American GI grandfather using DNA and genealogical research. She had then started helping other people look for their relatives in her spare time.

"My mother had been left with so many questions and this answered some of them and gave her a great sense of peace," Julia says.

"I believe everyone deserves to know who they really are."

Julia took on Robin's case and sent off saliva tests to three consumer DNA databases - Ancestry, 23andme and Family Tree DNA.

"We had lots of theories when we started. Lots of people told me I looked American and we thought maybe I was a GI baby, but they weren't over here in 1943," Robin says.

Soon there was exciting news - the 23andme results had provided a DNA match.

"She was called Maria in New York. I thought, 'Well that's it - we've done it!'" Lorraine says.

But it wasn't so simple.

The test showed Maria and Robin shared about 1% of their DNA, making them either second or third cousins."We contacted Maria and she agreed to collaborate to create a full family tree going back several generations to her 16 great-great-grandparents," Julia says.

"Our goal was then to bring each of these lines down to recent times to try and find a likely parent for Robin."

To give some idea of the scale of the task, if each of the great-great-grandparents and their descendants had just two children,

there would be 224 people who could be one of Robin's parents.

"We had no idea who would be the shared ancestor on the family tree. It's like the children's puzzle when you have to work out which is the right path that leads to the pot of gold," Lorraine says.

Working as a team, Julia and Lorraine used censuses, birth and marriage indexes and wills to reconstruct the family tree.

Results from Ancestry suggested Robin had a strong Scottish/Irish connection, which helped. When they felt they might be getting close, they would look to see whether a descendant could have been in the right place at the right time."I was working on it every night like someone possessed. Every time I had a breakthrough I'd get excited and it spurred me on," Lorraine says.

After a year of trial and error, and a number of dead ends, they tracked down a woman called Agnes, who had been born in Scotland and died in Canada.

"I had a strong hunch that this could be my dad's mother," Lorraine says.

She found a phone number for Agnes's son Grant, and rang one Saturday afternoon.

"I explained I was researching my dad's family tree and all the details. It went a bit quiet," Lorraine says.

"He said,

'That's really strange because when my mum got Alzheimer's she started talking as if she'd had another baby and would talk to me like I was that baby.'"

Grant agreed to take a DNA test, which Julia sent out to Canada. Lorraine suspected he would be a half-sibling, proving Agnes had had a wartime affair.

However, the results showed

Grant was actually Robin's full brother, meaning they shared both parents.

"I cried when Julia told me. I just couldn't believe it," Lorraine says.

Grant explained that Robin's parents were Douglas and Agnes Jones. Douglas was in the Royal Canadian Air Force and had met and married Agnes in Glasgow. The couple moved to Canada after the war ended and Douglas qualified as a psychologist. They had three more children - Karen, born 14 years after Robin, then Grant and another daughter, Peggy.

Lorraine drove over to Robin's house to tell him the news face-to-face.

"He was a bit upset and went out the room. Then he came back and we went through it all," Lorraine says.

Robin was surprised to discover that his parents had married in December 1942 - before he was conceived.

"If they didn't want me, why didn't they give me up for adoption?" he asks.

"It just doesn't make sense to me."

Sadly Robin can't get them to explain it to him. Douglas Jones died in 1975 and Agnes passed away in 2014.

"I feel like it was an opportunity lost. I would have gone over to meet her if I could," Robin says.

"I can see how Agnes and Douglas couldn't see a way of coping with war and a baby so early in their marriage.

"But I can't understand how you could leave a baby in central London, which was such a dangerous place at the time."

Robin's oldest sister, Karen, visited from Canada a few months ago. She told him that their parents had mentioned an earlier baby but said it had been stillborn.However, around this time, Lorraine also found Agnes's half-brother, Brian, who lives in Scotland, and he had heard

a different story - that Agnes had had a baby and given it up for adoption to an Air Force couple who were unable to have children.Though legal adoption had been possible since 1926 it remained common in the 1940s for one couple to simply agree to hand their child over to another. In September 1945, the

Evening Despatch newspaper quoted a medical officer who said: "More than once children have been handed from parent to adopting parent following a casual meeting in a queue or in an employment exchange."

Julia Bell believes

Robin could have been abandoned after such a handover went wrong. It's a scenario she has come across a number of times in her detective work.

"Imagine you've steeled yourself and no-one shows at the meeting place. You're not going to go back with the baby - it's going to have to be left," she says.

Lorraine says this would help explain some puzzling aspects of the story.

"Apparently my grandma was a lovely lady, a homely mum and really nice," she says, "which makes it hard to understand why she would do something like leave a baby."

Then there is a birth certificate, which reveals Robin was born on 10 October at a maternity unit in Winchester.

If Agnes had been planning to break the law by leaving her baby on the street, Lorraine thinks she would most likely have given birth at home, to prevent the birth being officially recorded.

But other details remain perplexing. One is that

the couple registered the baby's birth two weeks after abandoning him - and provided details such as his father's service number."I would have thought they'd put as little information as possible," Lorraine says.

They also gave him family names - Brian after Agnes's half-brother and Douglas after his father.

Robin and Lorraine had finally found their family, but they were still desperate to find someone who could tell them about the day he was left.

They made an appeal on BBC's Jeremy Vine show on Radio 2.

"We thought someone might have had a family story of finding a baby in London during the war," Lorraine says.

"It got our search out to more people but sadly it didn't lead to anything."

However, the BBC was able to fill in another piece of the jigsaw. It turns out 200 Oxford Street, which was part of Peter Robinson's department store, had been taken over by the BBC's Overseas Service in 1941. Staff, including the writer George Orwell, made regular radio broadcasts from the building during the war.

Trevor Hill, 92, was a junior programme engineer there at the time. And when asked if he remembered a baby being abandoned there during the war, remarkably he did - a baby wrapped in a blanket left in a box close to the front entrance."I worked at 200 Oxford Street and I do remember the baby in the box," he says.

"I did Home Guard duty for the BBC so when I saw the box I was slightly worried.

"We weren't allowed to leave deliveries or anything lying around because of security."

A couple of security guards went to check it - and discovered Robin inside.

"I imagine the baby was taken inside to the staff canteen where there was milk, although I doubt we had any bottles," Trevor says.

"We thought that the child's home might have been bombed and the mother had left it in desperation. It was typical of war time."

Recently, Robin and Trevor met near the spot where their paths had crossed nearly 74 years before. This end of the former Peter Robinson store is now a branch of Urban Outfitters.

"It's been a terrific experience to find someone who saw me at that time of life," Robin says.

The two men plan on exchanging Christmas cards this year.

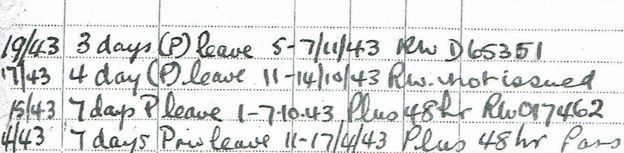

A few weeks ago Lorraine received another tantalising piece of information from Canada - a copy of Robin's father's war record.

It revealed that in October 1943 Douglas, a corporal, was an instructor at No 7 Radio School in South Kensington. It's probable he was staying in digs nearby at the time while Agnes was living near Andover.

Douglas was on leave for the week before Robin's birth on 10 October and for four days following it.

However, his file indicates he was back at work when Robin was found abandoned on Wednesday 20 October.He was almost certainly present when the now abandoned Robin was registered as Brian Jones. He was on leave from 5 to 7 November. Baby Brian was registered on 6 November.

Douglas's war leave record shows he was off on the day Robin was registered as Brian Jones

Lorraine and Robin know they are running out of new avenues to follow. They are waiting for a second adoption file to be opened but Robin doesn't think it will reveal the secret of why he was left.

They think Julia Bell's theory that an informal adoption went wrong may well be correct. However, they don't rule out the possibility that Douglas deliberately left the baby at the BBC, while telling friends and family the baby had been adopted. It's hard to be sure.But Lorraine and Robin have at least found some answers.

"It means a lot to find out what my dad's real name would have been and when he was actually born," Lorraine says.

It turns out that Robin has been celebrating his birthday four days too early, on 6 October. That's the date officials estimated he was born, when he was found in 1943. In fact, his birth certificate reveals, he was born on 10 October.

Robin hasn't decided yet which birthday to use in future, but he has no plans to change his name to Brian Douglas Jones.

As regards his nationality, he is getting used to the idea that he is not English, as he always assumed, but half-Scottish and half-Canadian.

"I am happy we went down this route," he says.

"It's astounding to see what Lorraine did through trial and error. But there are certain things I will never know about my past."

Reader Comments

I am very sorry for all those who miss their parents and for those who miss their children. May all stories open and reveal their reasons and mysteries.

[Link]

That's nonsense. Nobody in his/her right mind would do something like that. This idiot is saying that to defend her own lame theory of what happened.