© Lucy Nicholson / Reuters

In Los Angeles at the weekend I watched a terrific film that provides an illuminating if unintentional commentary upon the current furore.

Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri opens in the UK next month. The plot revolves around a woman called Mildred Hayes whose daughter has been raped and murdered.

Mildred is nearly driven mad by grief and rage over the fact that the murderer has not been caught. Convinced that this is because the police are indifferent to a brutal sex crime against a young girl, she uses three huge billboards to shame the local police chief into action.

The film is beautifully written and brilliantly acted and directed. It is a deeply black comedy which, through an often nightmarish and surreal plot, also conveys the bleakness of life for those who have been dealt an unfavourable hand by fate.

The point of the film, however, is not social commentary. It is instead to make a set of profound observations about guilt and forgiveness, and about human nature.

Real life, it says, is messy. The world is not binary. People don't fit neatly into boxes marked "good" and "bad". To be a victim is not necessarily to be morally pure. "Good" victims may be compromised by what they say or do; "bad" perpetrators may have decent instincts and themselves be victims of circumstances. Indeed, both Mildred and the violent police officer who treats her with derision are driven to do what they do by unbearable grief and rage.

Obviously it's desirable and necessary to bring a rapist and murderer to justice; but if that doesn't happen, well, sometimes it's no one's fault. That's just how life is.

Mildred is wrong to assume that it must have been caused by police indifference. That's just the projection of her terrible grief, her disbelief that life can be quite so unfair and her own guilty feelings. The reality is that the decent police chief did his best, but it wasn't enough.

Vengeance, as attempted by Mildred, does not create justice. It leads her to do terrible harm and turns others into her victims.

Ultimately, this is a film about forgiveness and redemption. People are redeemed not only if they repent for the harm they have done but also if they forgive those who have hurt them.

This is not to say that bad deeds can be brushed aside. The film certainly makes no excuses for rape or murder. Some of the men being accused at the moment are said to have committed serious sexual crimes; if so, they should be prosecuted. But the agenda behind the hysteria is clearly far broader.

For guilt is being assumed merely on the word of the accusers; and serious charges are being lumped together with minor lapses such as lewd or suggestive remarks or the kind of male flirtatiousness that was once regarded as acceptable.

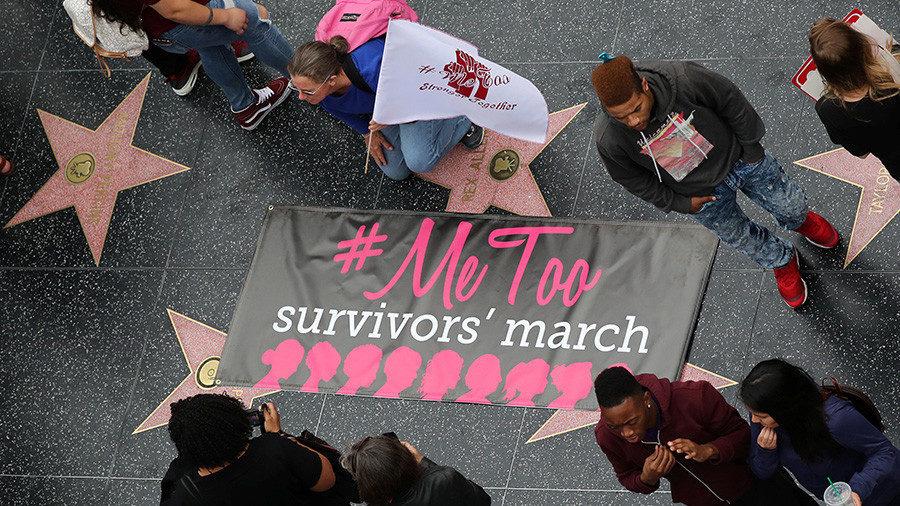

The purpose of this overreaction is to damn all chaps as congenital cavemen and portray women as victims of male patriarchy. It has little to do with justice, looking instead suspiciously like a campaign of collective vengeance against the male sex. It's the equivalent of putting up giant billboards across Britain, America and elsewhere to denounce, pillory and shame not only the perpetrators but those who are said to have pretended that this behaviour wasn't happening.

Some of those who turned a blind eye to it, however, were themselves women.

And although individual women were sometimes outright victims, what so many refuse to acknowledge is that this serial male misbehaviour is at least partly the result of the sexual revolution that was driven by women.Contrary to the notion of patriarchy, western women make and control the rules of the sexual game. For centuries, they thought their interests lay in getting their children's father to support the family.

So the bargain was struck between the sexes. Women would be sexually available only to the man who would father their children, thus providing the all-important guarantee that the children were indeed his and which was the greatest inducement to stick around.

Obviously those rules were frequently broken. The key point, though, was that everyone knew that those were the rules.

In the sexual revolution of the Sixties and Seventies, however, women tore them up and declared the bargain to be an oppressive relic of the past. Henceforth, men could be discarded as useless or worse, other than for their unavoidable biological contribution to the production of a child, and women would behave with sexual freedom. With the bargain no longer operative, many men assumed there were no longer constraints on their behaviour either. This doesn't in any way excuse the assaults, but the outrage over the widespread male assumption that so many women are "up for it" surely amounts to hypocrisy on a massive scale.The line between justice and vengeance may be narrow but it is clear. The self-deceptive sexual inquisition now under way has crossed that line. This fine film is an animated billboard that shames us for having done so.

However,

1) There's two sides to every story and we're not hearing that in many of these gripes.

2) As time grows, it's human nature to have memories grow more subjective, which is why there are such things as statutes of limitations.

For an example, there was an article on here by some girl who met a guy, slept with him after getting drunk with him at a bar, and claimed she got herpes from him, and she presented herself as having had a reasonable claim to argue. . . rape? I forget, but the mentality she displayed was typical and scary.) Link, anyone?

Also, it's crap like this that gives us the weakest, most boring, lowest common denominator types as our elected politicians. Anyone with real experience in the world will have lots of crazy events in their past that will preclude their ever getting elected.

R.C.