Just months ago, Boston Dynamic's humanoid bot became an object of ridicule after a series of accidents at a government 'robo olympics' saw if falling constantly, and needing a crane to get back on its feet.

Now, 'the World's Most Dynamic Humanoid' is back - and you really don't want to mess with it.

Its makers have given the bot an overhaul, and it is now so stable it can even perform a perfect backflip.

'Atlas is the latest in a line of advanced humanoid robots we are developing, Boston Robotics said.

'Atlas keeps its balance when jostled or pushed and can get up if it tips over.'

To stay upright, Atlas has stereo vision, range sensing and other sensors give Atlas the ability to manipulate objects in its environment and to travel on rough terrain.

According to Boston Dynamics, Atlas is a 'high mobility, humanoid robot designed to negotiate outdoor, rough terrain.

'Atlas can walk bipedally leaving the upper limbs free to lift, carry, and manipulate the environment.

'In extremely challenging terrain, Atlas is strong and coordinated enough to climb using hands and feet, to pick its way through congested spaces.'

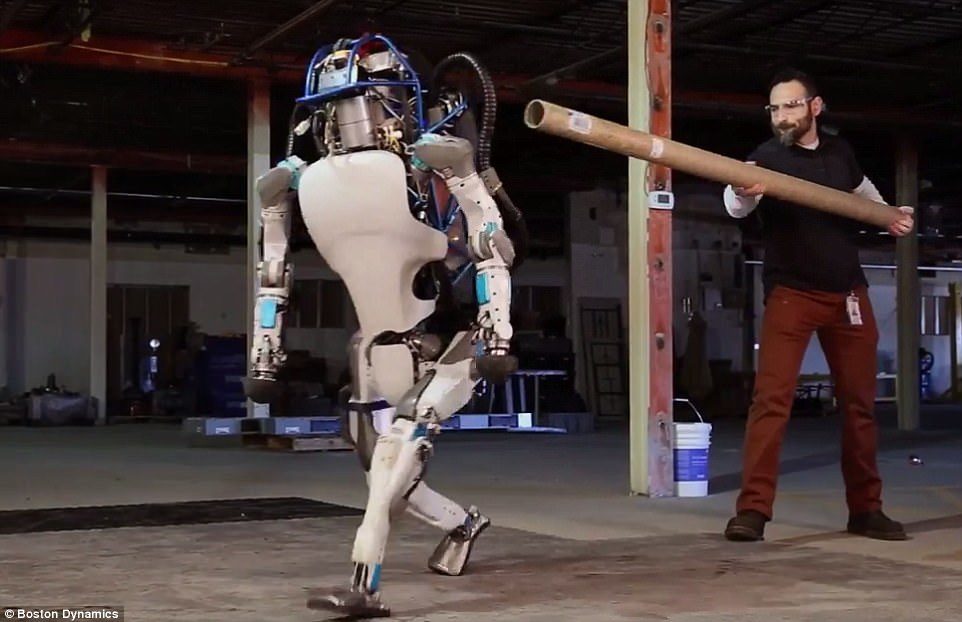

One recent video showed it being pushed over by an employee - and simply getting back up.

Boston Dynamics said the video showed 'a new version of Atlas, designed to operate outdoors and inside buildings.

'It is electrically powered and hydraulically actuated,' the secretive firm said.

'It uses sensors in its body and legs to balance and LIDAR and stereo sensors in its head to avoid obstacles, assess the terrain and help with navigation.

'This version of Atlas is about 5' 9" tall (about a head shorter than the DRC Atlas) and weighs 180 lbs.'

However, the firm released now more details - and the video has no narration.

The video shows the robot walking out of the firm's office and across a snowy plateau.

While losing its footing several times, it corrects itself and stays upright.

It is also shown moving 10kg boxes with ease in a tight space.

It then faces a more difficult foe - an employee with a hockey stick.

Last year's Robo-Olympics saw the world's most advanced robots go head to series in a series of ever more challenging events.

The DARPA Robotics Challenge (DRC) proved that robots still have some way to go before matching the dexterity of a human.

Twenty five of the top robotics organizations in the world were competing for $3.5 million in prizes, and took on a gruelling simulated disaster-response course during the two day contest.

'It was designed to be extremely difficult.

'We get most of our ideas about robotics from science fiction. And we want to show a little bit of science fact,' said Gill Pratt, who organized the competition for the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which focuses on futuristic technologies for national security.

The robots may be slow, clumsy and delicate but they might just save lives someday by braving dangerous disaster zones.

Pratt cited the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan as an emergency where such robots would have come in handy.

'Sometimes in a disaster, it is too dangerous for people to go in,' he said.

Teams of engineers, programmers and designers from research institutions across the world have worked for years to build robots that can maneuver the course and complete the assigned tasks.

'We have a valve that we need to turn to shut off a gas leak or something similar,' said John Seminatore, a Virginia Tech graduate student with Team Valor.

'We have to cut a hole in a wall to get access to something behind it. And there will be either rough terrain or rubble that we get past.'

The most difficult task - getting out of the small utility vehicle - is so hard that many teams aren't even attempting the dangerous egress, preferring to be docked on their times rather than risk toppling their robot into the dust.

'Robots don't have that sense of touch that humans do to know where they are inside the car,' Seminatore said. 'So it's going to be really nerve-racking for teams because the training wheels have come off.'

The robots come in all shapes and sizes.

Most appear humanoid but some can switch to wheels to get around.

'RoboSimian' looks like a double-jointed monkey without a head.

Another has a torso on a 4-wheeled base, like a centaur.

Several teams used DARPA's Atlas robot as a start for their own designs.

'This robot weighs almost 400 pounds with the battery and hydraulics,' Cassie Moreira of Boston Dynamics said as she worked on the knees of a robot from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

DARPA's first robot competition in 2004 was a race for driverless cars.

None of the entries finished and most made it only a few miles.

But 11 years later, Google's driverless cars are cruising.

Pratt says that means the competitions are a success.

So even if the robots struggle to exit a car this year, their designers will learn. And when DARPA issues a challenge and invites the public to watch the results, it means the Pentagon's 'mad science' division is serious about disaster response robots.

'What I love about this is it introduces everybody to the new dream.

'his is something you can do right now,' said Jonathan Daniels, who teaches robotics at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

'Give me five years and we'll have this in high schools.'

'Participating teams, representing some of the most advanced robotics research and development organizations in the world, are collaborating and innovating on a very short timeline to develop the hardware, software, sensors, and human-machine control interfaces that will enable their robots to complete a series of challenge tasks selected by DARPA for their relevance to disaster response.'

The winning team will receive a $2 million grand prize; DARPA plans to award $1 million to the runner-up and $500,000 to the third-place team.

Tasks are 'put together in a single mission' that teams have one hour to complete, Pratt said.

The robots will start in a vehicle, drive to a simulated disaster building, and then they'll have to open doors, walk on rubble, and use tools.

Finally they'll have to climb a flight of stairs.

After this, there will be a surprise task waiting for the robots at the end.

Spectators have been encouraged to watch the event, and will see a quartet of virtually identical Finals Courses, or what Kathy Wadham, director of creative programming for Fairplex, thinks of as stage sets.

'Anything that needs to be turned into something else, or created here, we do that,' said Wadham during a backstage tour of the concocted disaster zones the robots will have to navigate over and through.

'We went through our scrap piles to find the doors and the electrical switches,' she said.

Those same piles were a gold mine for creating the debris fields in front of the steel staircases on the left side of each set.

Each junk heap is an assemblage of rooftop turbine vents (some with long-abandoned birds' nests inside), gas line piping, beat up steel drums, water heater vessels, and sundry other pieces of detritus.

'Some of the stuff was not rusted enough at first,' she said. 'So we have a person who rusts and weathers it and makes it look old.'

For some of the details on the set, Walham went shopping.

She found the incandescent bulbs for the dingy metal mesh fixtures online and purchased decals of gauges for the square electrical cabinets from a store specializing in retro design.

'We create places,' says Wadham. 'That's what we do.'

Reader Comments

'This Crazy New Material Could Harvest Electricity From The Human Body'....[Link]