Since then, Zimbabwean broadcasters have been off air, with reports emerging that the Army has taken control of the state broadcaster, a move which often signals that a general coup is taking place against the government.

As of last night and early this morning, local time, telecom services in Zimbabwe were switched off, meaning that information has been slow to emerge and when news items do come out of Harare, are often marred in contradiction.

The first statement to emerge was from the Army itself. An officer appeared on ZBC television and said that no coup is taking place but rather, that certain figures "committing crimes that are causing social and economic suffering in the country". The statement continued,

"As soon as we have accomplished our mission, we expect that the situation will return to normalcy".The Army's statement further assured the country that President Robert Mugabe and his family are safe.

Comment: Joaquin Flores at Fort Russ comments:

Mnangagwa has tremendous pull with the military and with General Constantine Chiwenga, as he played a major role in the country's liberation wars.

With mounting pressure on Mugabe from the west over the last decade and a half, it is unclear at this moment to what extent this plot also involves the United States. It is a complex situation to assess because while the US has stated its desire to remove Mugabe, inter-party disputes over succession are the apparent cause. Mugabe has not directly said that Mnangagwa is backed by foreign forces, only that he is 'ideologically' not 'solid'.

...

The ZANU-PF website, the part which Mugabe heads, has not updated its site since November 8th. We have not found any access to other official information online from the Mugabe side of these events. On November 8th, explaining the internal party struggle, Mugabe said last:

<< President Mugabe said he had knowledge of the shenanigans that were being organised. ... President Mugabe has told the gathering here that he has known for some time, of the plots by his beleagured former deputy. ...

Mujuru, according to President Mugabe wanted to compete with him. But Mnangagwa played the loyalty card yet scheming and aligning people for future take over. He would mislead people and if what he told them does not come to fruition, he would conjur up other lies again. "People were told that I will retire in March, but i did not. Upon realising that I wasn't, he started to consult traditional healers on when I was going to die. At some point, he was told that he would die first before me."

President Mugabe says his former deputy lacked the supreme discipline and he would infiltrate the structures trying to influence rebellious conducts. ... "You can not claim to be the greatest because you come from a particular province. We are one people. ...">>

However, a statement from a representative of Harare's city government offered a summation of events which seems to imply that business is progressing in a normal way and that there are seemingly fewer Army vehicles on the streets than initially reported. The statement from City Hall read,

"We're doing our work normally, and everybody is at work as usual. Public transport is available and people are going to work. Access to the City Hall is open. I'm in my office right now. Everybody is at work. We are doing our work as normal. There's no one from the military here".However, a more ominous message came shortly thereafter from the ruling ZANU-PF party of President Mugabe. The official Twitter of ZANU-PF has released the following statements:

These statements would appear to indicate that the ruling party of Zimbabwe along with the Army have conspired together to remove President Mugabe from power but that he and his family are personally safe.

A cryptic warning from the Twitter of ZANU-PF from the 4th of September stated "There is a storm coming". In hindsight, this may indicate that the events of yesterday and today were planned several months in advance.

Hours ago, South African President Jacob Zuma called for calm and stated that he spoke to President Mugabe who is "confined to his home but said that he was fine".

Zuma's statement would appear to corroborate that of ZANU-PF. It can therefore be assumed with some measure of confidence that Mugabe is effectively under house arrest while de-facto out of power, even though he remains the internationally recognised President of Zimbabwe.

Zuma issued a further call for calm via the South African government's Twitter,

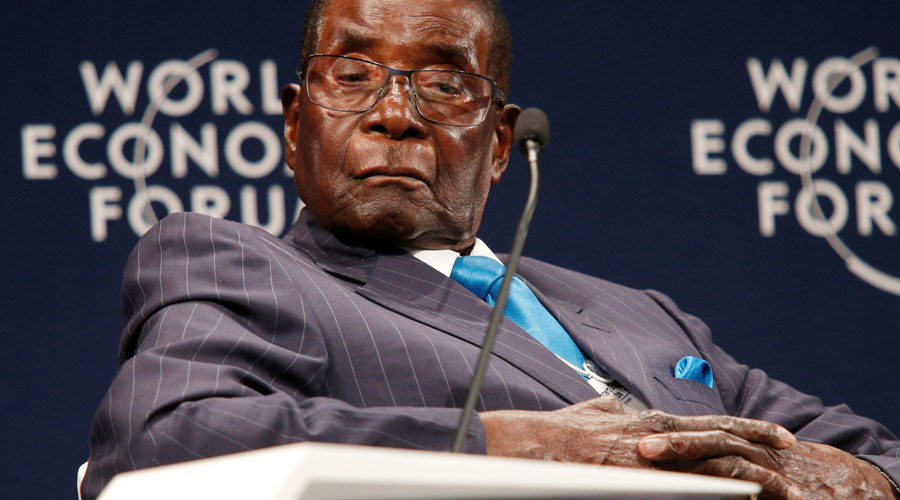

Robert Mugabe who has been President of Zimbabwe since 1987 while being Prime Minister prior to that, starting in 1980, is a political survivor against many odds, both foreign and domestic.

Throughout the 1970s, Mugabe led the Maoist Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) in the struggle against the government of Ian Smith, the leader of what was then Rhodesia's Unilateral Declaration of Independence from Britain in 1965. Smith went on the rule the widely unrecognised state of Rhodesia from 1965 until its collapse in 1979. While in power, Smith presided over a government whose members were compromised overwhelmingly of Rhodesia's white minority, a situation the black majority found unacceptable.

Mugabe's ZANU faction was rivalled by another black liberation party, Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) led by the Marxist-Leninist Joshua Nkomo. Against the background of the Sino-Soviet rivalry ZANU was favoured by China while ZAPU was favoured by the Soviet Union with Smiths' government winning favour almost exclusively from South Africa as well as right wing politicians in Britain, Australia, Canada and the United States.

In 1979, Britain held talks between all sides in what led to the Lancaster House Agreement. This agreement temporarily brought what by then was called Zimbabwe-Rhodesia back under British rule as Southern Rhodesia, before fully gaining independence as Zimbabwe in 1980.

Mugabe became the first Prime Minister of Zimbabwe, working with both his black pro-Soviet rival Nkomo as well as Ian Smith who under the terms set out in the new constitution, was able to retain a bloc of seats in the parliament specifically designated for the white minority. In 1983, Mugabe had his penultimate falling out with Nkomo, who later fled the country.

In 1987, Smith whose relationship with Mugabe became increasingly tense, stepped down as the leader of the white opposition movement, the Conservative Alliance of Zimbabwe.

That same year Mugabe moved from the office of Prime Minister to President, in an increasingly strong presidential system, as opposed to the previous parliamentary driven government.

In the subsequent years, Mugabe instigated his land reform programme which saw the private holdings of white farmers transferred to black ownership. The move proved deeply unpopular with the white minority, but won Mugabe acclaim in both Zimbabwe and among the black population of Apartheid South Africa.

By the turn of the 21st century, Mugabe's position was widely unassailable, but rampant inflation proved to cause consternation among a majority of Zimbabweans.

More recently, the prospect of further investment from Mugabe's consummate ally China, has brought hope of economic renewal for Zimbabwe.

At 93 years old, the biggest threat to Mugabe's rule has been the largely accurate perception that when he dies, he intends to pass power onto his deeply unpopular wife Grace.

Grace remains a polarising figure and her rise to power could well have been a proximate cause of the apparent coup. The careful, though by no means perfect, tribal balancing act that has allowed Mugabe to remain in power could be threatened by a leader such as his wife.

That being said, South Africa is in a position to restore Mugabe's rule should President Zuma believe that a constitutional crisis in neighbouring Zimbabwe threatens regional stability. Furthermore, some members of Zuma's African National Congress and other smaller left-wing parties in South Africa continue to view Mugabe as a hero of the anti-colonial black liberation movement.

For the moment, Zuma has called for calm, but his words indicating that peace and stability must not be "undermined", does leave the door open for a South African intervention to restore Mugabe's legal power should Zuma feel that such a thing is worth it.

While some have been quick to say that the events in Zimbabwe are foreign "regime change", the realities on the ground do not yet indicate this. It is true that foreign powers pump money into many of Mugabe's political opponents in Zimbabwe, but the fact that the once highly loyal army along with Mugabe's own left-wing party appear to have willingly participated in procuring his and Grace's house arrest, indicates that the events in the country are domestic in origin.

In this sense, the 'coup' against Mugabe is somewhat similar in terms of its likely effects as was the judicial ouster of former Pakistani Premier Nawaz Sharif. While the Supreme Court in Islamabad removed Sharif from office, his party remained and the policies of the Pakistani government remained largely the same. If the 'coup' in Zimbabwe is successful, something similar will likely happen in Zimbabwe, especially as it relates to the country's long-term good relations with China, relations which will almost certainly continue to remain positive under a would-be successor to Mugabe plucked from the ranks of the ZANU-PF elite.

While even some of Mugabe's erstwhile supports have become fatigued with his omnipresent rule in the country, Mugabe has previously faced off challenges with comparative ease. So long as Robert Mugabe is alive and well, which apparently he is, there is always a chance that either with the help of his loyal lieutenants or with the help of South Africa, he could restore his position. It is still too early to write off the future prospects of a man who is a true political survivor in a continent that has had more violent power struggles than any other.

Comment: See also:

- Bitcoin climbs to $13,500 in Zimbabwe following news of military coup and currency shortages

- End of the road for Robert Mugabe? Military tanks on streets of Harare - China denies involvement in apparent Zimbabwe coup

Today, Coup General Constantino Chiwenga of the rogue faction of the Zimbabwe Defense Forces made the following statement on TV, insisting that Mugabe remains president (Garrie quotes bits of the statement above):