Now, roughly five months into his administration, we see how the things have played out. Not only is Trump president, but his Twitter base has grown from 5 million to 31 million. Instead of acknowledging the advent of a potent new mode of presidential communication, the very people Trump is trying to bypass — the traditional media — have derided and mocked his use of this technology. To be sure, the president's indiscriminate and sometimes intemperate tweets have made an irresistible target. In the past few days, he has used Twitter to pick an odd fight with London's mayor while seemingly undermining the Justice Department's legal rationale of his travel ban.

Yet the Fourth Estate's knee-jerk opposition to Trump does a disservice to the electorate.

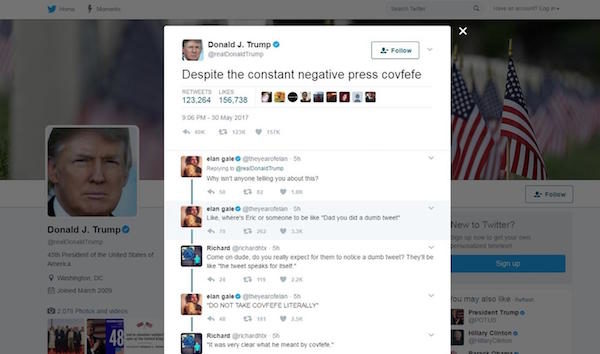

Consider, for example, Trump's inscrutable "negative press covfefe" tweet early in the morning of May 31, a term that currently has 52 million search results on Google. It's easy to see why: Print and broadcast news outlets pounced on the abbreviated tweet and hyperventilated for days.

This is precisely the problem: Most of Trump's tweets, especially this sort, should not be reported as breaking news. As Michael Barone, the longtime co-editor of The Almanac of American Politics and senior political analyst for the Washington Examiner, points out,

"Early on, he [Trump] realized that by sending out a tweet early in the morning, that was very provocative, very in violation of political correctness, he could dominate an entire news cycle."What's more, Trump knew he could feed the media's "addiction" to anything remotely resembling "breaking news," all to his benefit.

This failure of U.S. broadcast media to use proper news judgment in covering Trump is among the gravest professional sins the industry has committed in recent memory because it fails to recognize the manipulation involved. George Lakoff, a professor emeritus of linguistics at the University of California, Berkeley, asserts that Trump's tactics are "all strategic" in nature, "not crazy," as many observers believe.

Lakoff has written several books on political speech and is an expert on the concept of idea framing, which has become an influential technique in the art of political persuasion. He asserts that Trump's tweets embody one of four strategic communication tactics: preemptive framing, diversion, deflection and trial-ballooning.

"In general, if you frame first you win, and Trump knows that," Lakoff said. "The media is having trouble with the truth because the truth doesn't sell - and they could sell it if they went about it the right way," he added. "Right now they can't help themselves, having the entertainment elements of their job take over for the news element."If Lakoff's theory is true, the failure of the most influential elements of the U.S. media to exercise proper news judgment when assessing Trump's tweets has had a greater negative impact on the country's political discourse than is appreciated.

The roots of this vulnerability are entwined with a soft spot in our political system. As Barone has mentioned in the past, the weakest part of American politics is the presidential nomination process, in large part because the U.S. Constitution gives no guidance in such matters and because the Founders feared the creation of political parties.

But parties formed nonetheless, and through the 1960s their nominating conventions were the centralized method by which bosses tried to maximize their nominees' electability. They did this in part by spotlighting information that was not generally available to the public about the policies and personality of a particular candidate.

But as excluded voices began to agitate for reform in the nomination process, the Democratic Party altered its process after the protests at the 1968 Chicago convention, allowing each state to hold primaries or caucuses. The Republican Party quickly followed suit, giving the news media a quasi-constitutional responsibility to vet candidates during a primary season that didn't exist in other democracies, especially those with parliamentary systems.

This decentralized nomination system worked for a while, but as newsrooms felt the strain of economic pressures and the static three-network broadcast news era gave way to 24/7 cable operations, entertainment began to trump news value.

Over time, these market forces lengthened the campaign season by almost a year, boosting the need to raise money to pay for media exposure, which in turn created both a greater supply and a greater demand for political speech. This reached its apogee during Trump's circus-like, taboo-shattering transgressive candidacy, which created a feedback loop that generated billions of dollars in free airtime.

In the two years since then, not much has changed in the coverage.

"Donald Trump may not be good for the country, but he's good for CBS," said CBS Chief Executive Leslie Moonves in late Feb. 2016, as Trump was solidifying his lead in the Republican primaries. "Man, who would have expected the ride we're all having right now? ... The money's rolling in and this is fun," he said.But the thrill of "the ride," as anyone who's spent too much time on an amusement park roller coaster knows, doesn't just wear thin after a while. It can make you ill. The nation's media outlets should bear that in mind.

On my personal scale I have ceased watching CNN, refure to read, pay for or even acknowledge the existence of WaPo, NYT.

They are 'nefas'. Der Angriff and Der Sturmer.

I repudiate the credibility of their culture. They are not journalists, news media. They are a partisan political propaganda agency posing as a legitimate news media. They should be required to register as lobbyists. They are racketeers.