And it isn't just a liberal reflex. A few months ago, George W. Bush spoke at a memorial service in Dallas for five slain police officers and said, "At our best, we practice empathy, imagining ourselves in the lives and circumstances of others." As a candidate, even Donald Trump asked Americans to identify with the suffering of others, from displaced Rust Belt factory workers to the victims of crime by undocumented immigrants.

Though there are obvious ideological differences over who deserves our empathy, it is one of the rare political sentiments that still command a wide consensus. And that's a shame, because when it comes to guiding our decisions, empathy is a moral train wreck. It makes the world worse. When we have the good sense to set it aside, we are better people and make better policy.

What do we mean by empathy? Some use the word to describe what psychologists call cognitive empathy—that is, the capacity to understand what's going on in the minds of other people, without necessarily sharing their feelings. Empathy in this sense is essential; you can't act effectively in the world if you don't have some sense of what other people want. But it isn't inherently a positive force. High cognitive empathy is also necessary for a successful con man, seducer or torturer.

When most of us talk about empathy, we mean what psychologists call emotional empathy. This goes beyond mere understanding. To feel empathy for someone in this sense means that you share their experiences and suffering—you feel what they are feeling.

This is an important part of life. Such empathy amplifies the pleasures of sports and sex, and it underlies much of the appetite we have for novels, movies and television. Most of all, people want to share the feelings of their friends and romantic partners; it's a basic part of intimacy.

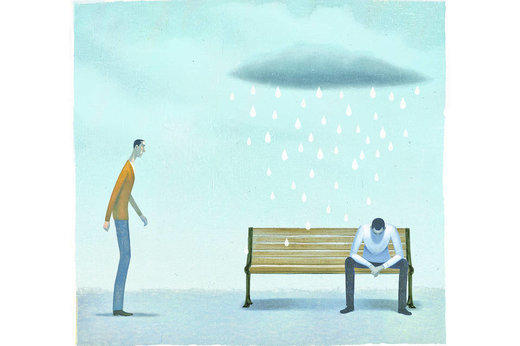

But emotional empathy is a different matter when it comes to guiding our moral judgments and political decisions. Recent research in neuroscience and psychology (to say nothing of what we can see in our everyday lives) shows that empathy makes us biased, tribal and often cruel.

Much of the science of empathy involves scanning subjects' brains while subjecting them to certain experiences (usually mildly painful ones such as an electric shock, a pinprick to the finger or a blast of noise through headphones). These scans are then compared with how their brains respond when watching others being shocked, pricked or blasted.

No matter how you test it, there is neural overlap: Your brain's response to your own pain—in areas such as the anterior insula and the cingulate cortex—is similar to how it responds when you empathize with someone else's pain. Bill Clinton's response was more than a metaphor—to some extent, we literally do feel the pain of others.

Such studies also find, however, that empathy is biased. Some of these biases are superficial, based on considerations like ethnicity and affiliation. One study, published in 2010 in the journal Neuron, tested European male soccer fans. A subject would receive a shock on the back of his hand and then watch another man receive the same shock. When the other man was described as a fan of the same team as the subject, the empathic neural response—the overlap in self-other pain—was strong. But when the man was described as a fan of an opposing team, it wasn't.

Other biases run deeper. You feel more empathy for someone who treated you fairly in the past than for someone who cheated you, and more empathy for someone you have cooperated with than for a competitor.

And empathy shuts down if you believe someone is responsible for their own suffering. A study published in 2010 in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience showed people videos of individuals said to be suffering from AIDS. When they were described as being infected through intravenous drug use, subjects felt less empathy than if they were described as being infected by a blood transfusion.

Our empathic responses are not just biased; they prompt us to ignore obvious practical calculations. In studies reported in 2005 in the Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, researchers asked people how much money they would donate to help develop a drug that would save the life of one child, and asked other people how much they would give to develop a drug to save eight children. The research participants were oblivious to the numbers—they gave roughly the same in both cases. And when empathy for the single child was triggered by showing a photograph of the child and telling the subjects her name, there were greater donations to the one than to the eight.

Empathy is activated when you think about a specific individual—the so-called "identifiable victim" effect—but it fails to take broader considerations into account. This is nicely illustrated by a classic experiment from 1995, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Subjects were told about a 10-year-old girl named Sheri Summers who had a fatal disease and was low on a wait list for treatment that would relieve her pain. When subjects were given the opportunity to give her immediate treatment—putting her ahead of children who had more severe illnesses or who had been waiting longer—they usually said no. But when they were first asked to imagine what she felt, to put themselves in her shoes, they usually said yes.

We see this sort of perverse moral mathematics in the real world. It's why people's desire to help abused dogs or oil-drenched penguins can often exceed their interest in alleviating the suffering of millions of people in other countries or minorities in their own country. It's why governments and individuals sometimes care more about a little girl stuck in a well (to recall the famous 1987 case of Baby Jessica in Midland, Texas) than about crises that affect many more people.

It's also why we get so concerned when it comes to the immediate victims of policies—someone who is assaulted by a prisoner who was released on furlough, a child who gets sick due to a faulty vaccine, someone whose business goes under because of taxes and regulation—but we are relatively unmoved when it comes to the suffering that such policies might avert. A furlough program might lead to an overall drop in crime, for instance, but you can't feel empathy when thinking about a statistical shift in the number of people who are not assaulted.

In moral and political debates, our positions often reflect our choice of whom to empathize with. We might feel empathy with minorities abused and killed by law enforcement—or with the police themselves, whose lives are often in peril. With minority students who can't get into college—or with white students turned away even though they have better grades. Do you empathize with the mother of a toddler who shoots himself with a handgun? Or with a woman who is raped because she is forbidden to buy a gun to defend herself? With the Syrian refugee who just wants to start a new life, or the American who loses his job to an immigrant?

Such empathic concerns can lead to hostility. Consider that the most empathic moments in the 2016 election season came from the president-elect, in his attacks on undocumented immigrants. Donald Trump wasn't stirring empathy for the immigrants, of course, but for those he described as their victims, those putatively raped and assaulted and murdered.

We can see the connection between empathy and aggression in the laboratory. In one clever study from 2014, published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, subjects were told about a financially needy student who was entering a mathematics competition for a cash prize. When motivated to feel empathy for the student, subjects were similarly motivated to torment the student's competitor—by assigning large doses of hot sauce for her to consume—even though she plainly had done nothing wrong.

Given all these problems with empathy, it's a good thing that we can use rational deliberation to override its pull. Most people would agree, on reflection, that these empathy-driven judgments are mistaken—one person is not worth more than eight, we shouldn't stop a vaccine program because of a single sick child if stopping it would lead to the deaths of dozens. We can appreciate that any important decision—about criminal justice, diversity policies in higher education, gun control or immigration—will inevitably have winners and losers, and so one can always find someone to empathize with on either side of the issue.

Comment: Point taken, but the use of vaccines as an example is over the top. It's not "a single sick child". The fact is, a large but as-yet-unidentified group of children have extremely negative reactions to vaccines. (Not to mention the fact that vaccines are not proven to actually work - outbreaks often occur among previously vaccinated children.) It's like force-feeding all children peanut-butter sandwiches without first identifying which children are allergic - not smart.

What about our motivation to be good people? If we don't empathize with others, don't feel their pain, why would we care enough to help them? If the alternative to empathy is apathy, then perhaps we should stick with it, regardless of its flaws.

Fortunately, empathy isn't the only force motivating us to do good. Empathy can be clearly distinguished from concern or compassion—caring about others, valuing their fates. The distinction is nicely summarized by the neuroscientists Tania Singer and Olga Klimecki in a 2014 article for the journal Current Biology: "In contrast to empathy, compassion does not mean sharing the suffering of the other: rather, it is characterized by feelings of warmth, concern and care for the other, as well as a strong motivation to improve the other's well-being. Compassion is feeling for and not feeling with the other."

In a series of studies that I conducted with Yale graduate students Matthew Jordan and Dorsa Amir, just published in the journal Emotion, we compared people's scores on two different scales, one measuring emotional empathy and another measuring compassion. As predicted, we found that the scales tap different aspects of our nature: You can be high in one and low in the other. We found as well that compassion predicts charitable donations, but empathy does not.

There is also the body of research, led by Tania Singer, in which people were trained to experience either empathy or compassion. In empathy training, people were instructed to try to feel what suffering people were feeling. In compassion training—sometimes called "loving-kindness meditation"—they were told to direct warm thoughts toward others, but they were not to feel empathy, only positive feelings.

Their brains were scanned while they did this, and it turns out that there was a neural difference in the two cases: Empathy training led to increased activation in the insula and cingulate cortex, the same parts of the brain that would be active if you were empathizing with the pain of someone you care about. Compassion training led to activation in other parts of the brain, such as the ventral striatum, which is involved in, among other things, reward and motivation.

These studies also revealed practical differences between empathy and compassion. Empathy was difficult and unpleasant—it wore people out. This is consistent with other findings suggesting that vicarious suffering not only leads to bad decision-making but also causes burnout and withdrawal. Compassion training, by contrast, led to better feelings on the part of the meditator and kinder behavior toward others. It has all the benefits of empathy and few of the costs.

These results connect nicely with the recent conclusions of Paul Condon and his colleagues, published in the journal Psychological Science in 2013, who found that being trained in meditation makes people kinder to others and more willing to help (compared with a control condition in which people were trained in other cognitive skills). They argue that meditation "reduces activation of the brain networks associated with simulating the feelings of people in distress, in favor of networks associated with feelings of social affiliation." Limiting the impact of empathy actually made it easier to be kind.

I don't deny the lure of empathy. It is often irresistible to try to feel the world as others feel it, to vicariously experience their suffering, to listen to our hearts. It really does seem like a gift, one that enhances the life of the giver. The alternative—careful reasoning mixed with a more distant compassion—seems cold and unfeeling. The main thing to be said in its favor is that it makes the world a better place.

Dr. Bloom is the Brooks and Suzanne Ragen Professor of Psychology at Yale University. This essay is adapted from his new book, "Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion," which will be published next week by Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins (which, like The Wall Street Journal, is owned by News Corp).

Comment: Polish psychologist Kazimierz Dabrowski differentiates between automatic, reflexive "syntony" (feeling something in common with others), and conscious, reflective empathy. As Bloom demonstrates above, the first is fickle, unreliable, and can lead to contradictory results. It also leads to a kind of 'mob' mentality in groups. But the second has all the advantages of the first, without the drawbacks: