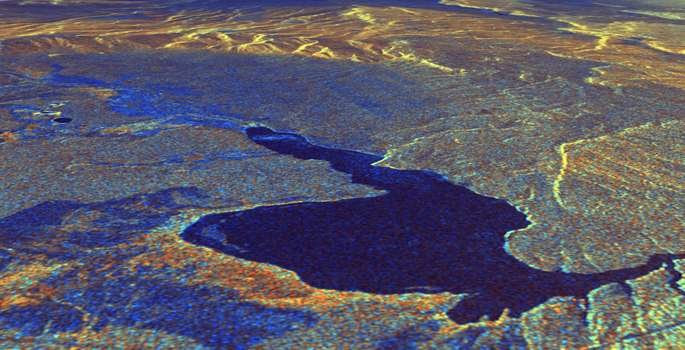

That is the conclusion of a new microscopic analysis of quartz crystals in pumice taken from the Bishop Tuff in eastern California, which is the site of the super-eruption that formed the Long Valley Caldera 760,000 years ago.

The study is described in the paper "The year leading to a supereruption" by Guilherme Gualda, associate professor of earth and environment sciences at Vanderbilt University, and Stephen Sutton at the University of Chicago published July 20 in the journal PLOS One.

"The evolution of a giant, super-eruption-feeding magma body is characterized by events taking place at a variety of time scales," said Gualda. Tens of thousands of years are needed to prime the crust to generate sufficient eruptible magma. Once established, these melt-rich, giant magma bodies are unstable features that last for only centuries to few millennia. "Now we have shown that the onset of the process of decompression, which releases the gas bubbles that power the eruption, starts less than a year before eruption."

Gualda and Sutton analyzed dozens of small quartz crystals from the Bishop Tuff. Previous investigations of quartz crystals from several super-eruptions, including Long Valley, have noted that they have distinctive surface rims. These studies concluded that the rims formed in less than a century before eruption.

The new study uses a more accurate method for measuring rim growth times pinned on variations in the concentration of titanium in the crystal. Titanium is one of the few impurities that is incorporated into quartz in appreciable amounts and it diffuses fast enough to permit probing of time scales as short as minutes. However, it is extremely difficult to measure the small levels of titanium involved at sufficient spatial resolution. So the researchers established that the concentration of titanium in quartz directly correlates with the amount of light produced when a material is bombarded by electrons, an effect called cathodoluminescence. This allowed them to use cathodoluminescence images to make high-resolution measurements of variations in titanium concentration and, based on this, to determine rim growth times and growth rates.

According to Gualda, the decompression period would likely be accompanied by the expansion of the magma body which should have detectable effects on the Earth's surface. While more work is needed to understand what exactly the signs at the surface would be, the study suggests that signs of an impending super-eruption would start to be felt within a year of eruption, and they would intensify as the eruption neared.

Very large eruptions—including super-eruptions—have taken place in a number of places worldwide in the recent geological past. The Taupo Volcanic Zone in New Zealand was the site of the most recent super-eruption—the Oruanui eruption at 26,500 years—and it includes deposits from more than a dozen very large eruptions that took place in the last couple of million years. Campi Flegrei in Italy produced a very large eruption 40,000 years ago. Indonesia was the site of the Toba super-eruption in Sumatra 75,000 years ago and the Tambora eruption in 1815. In the United States, Yellowstone has experienced three super-eruptions over the last two million years. In light of this evidence, it seems inevitable that another super-eruption will strike the Earth in the future.

"As far as we can determine, none of these places currently house the type of melt-rich, giant magma body needed to produce a super-eruption," said Gualda. "However, they are places where super-eruptions have happened in the past so are more likely to happen in the future."

Gualda and Sutton's study provides new insights into the timescales over which the initiation of such a potentially civilization-ending event would take place.

Journal reference: PLoS ONE

Comment: Magma May Give Signs of Super-Volcano Eruptions