Pre-Civil War Chicago had been a sleepy little cow town on the shore of Lake Michigan, with a population of around 30,000. But during and after the war, the United States underwent one of the most rapid industrializations of any country in the world, and Chicago was one of its economic centers. Strategically located in the middle of the country, the town became a railroad hub and an important shipping port on the Great Lakes. Industries crowded in; the McCormack Reaper Company was the biggest manufacturer of farm machinery in the country, and the huge meatpacking industry earned the city the nickname "Hog Butcher to the World". This in turn attracted immigrants from Ireland, Germany, Norway, Italy and elsewhere who were eager to feed the insatiable appetite of the factories and packing plants for cheap labor. By the end of the Civil War, Chicago had a population over 100,000, and by 1870 it was over 300,000.

But the explosive growth was too rapid for the city to keep up. The well-to-do lived in stately stone homes on the outskirts of the city, connected by the extensive railroad network, while the immigrant workers with their horse-drawn carts crowded into the city center, paying high rents for small rooms in overcrowded flimsy multi-story wooden tenements. In the Downtown business district, hastily-constructed buildings were made of wood timber, covered with a face of thin brick to make it look more elegant. Even the city streets were paved with wooden planks instead of stone.

It was, the fire department recognized, a disaster waiting to happen--any accidental fire could easily sweep across the entire city. In 1858, Chicago became one of the first large cities in the US to establish a city-run professional firefighting service, with 185 fulltime firemen. But at budget time, the fire department was often neglected. The fire chief asked for more hydrants, better equipment, and an inspection program to tear down and replace unsafe buildings--all in vain. The city government wanted to keep the taxes low to continue to attract businesses and factories.

Comment: Chicago was no stranger to fire. In fact, in 1870, the city suffered through an average of two fires a day. [link]

The summer of 1871 was one of the hottest and driest on record. Barely an inch of rain fell in a 90-day period, only one-fourth the normal level. By October, the residents who had horse-drawn carts were preparing for winter by stockpiling hay in their stables and barns. One of these barns was on DeKoven Street on the West Side. It belonged to Mrs Kate O'Leary, her husband Patrick, and their five children. The family made their living by selling milk and butter from the five cows and one calf that were housed in the barn behind their house.

There had already been a number of small fires that week, started by cooking, careless smoking, or some other accident. All had been quickly dealt with by the city firefighters, who were maintaining a 24-hour watch from fire towers placed around the city. When smoke or flames were spotted, the lookouts were able to direct horse-drawn fire engines to the location using a grid map, and quickly put out the blaze before it spread. On the afternoon of October 7, 1871, a large fire had broken out that leveled four city blocks in 17 hours before the firefighters, working all night, could bring it under control.

Early the next evening, October 8, a lookout saw smoke rising from DeKoven Street and sounded the alarm. But he mistakenly gave the wrong grid coordinates, sending the firefighters about a mile away. It was all the time the fire needed; by the time the fire carts reached the right location, the entire block was ablaze and sparks were already being blown to the northeast, towards Downtown. One of the earliest victims was the city waterworks on Pine Street, where the fire department got its water.

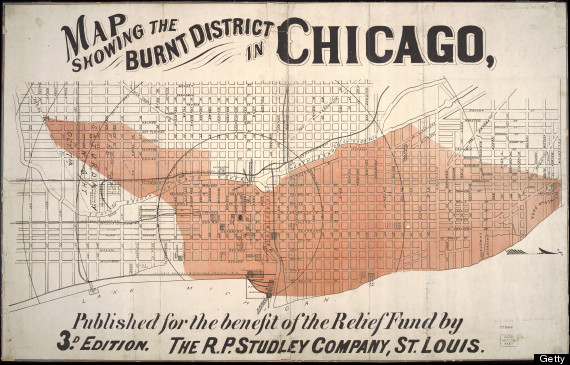

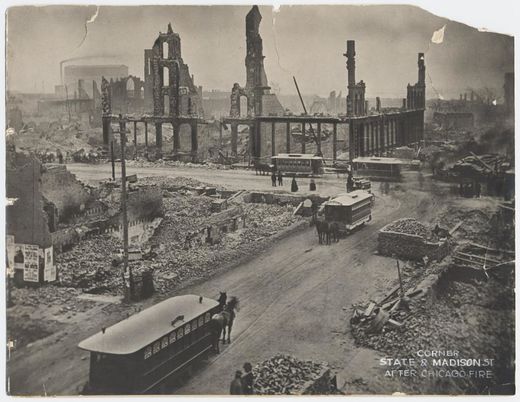

As firemen stood by helplessly, the flames jumped relentlessly from block to block. As the hot air rose into the sky, it pulled in cooler surrounding air, which produced a phenomenon known as a "fire tornado" with winds over 50 miles per hour, ejecting sparks and flaming debris that caused the fire to spread further. The city burned all night and all through the next day. In total, some 3.5 square miles--one third of Chicago--were incinerated. Most of Downtown and much of the North Side was destroyed. Over 17,000 buildings burned, leaving 100,000 residents homeless. Panicked people were driven through the streets by the heat and smoke; horses, dogs, rats and pigeons all roasted in the flames, and trees were seen to explode as the sap inside them boiled in the heat. Thousands of people sought escape by wading into Lake Michigan. Although only 120 bodies were recovered, almost 200 more Chicagoans had been reported missing, and it was assumed their bodies had been reduced to ashes in the conflagration. The fire raged for almost 24 hours before a rainstorm moved in and soaked the city.

In the aftermath, investigators were able to trace the fire's origin to DeKoven Street, in the area of Mrs O'Leary's barn--either at the barn itself or in the next-door property belonging to Daniel Sullivan. The investigators were unable to discover what had actually sparked the blaze, but the press weighed in with theories of its own. One theory was that the fire had been intentionally set by "incendiaries" in the city's large and active socialist and anarchist union movement. Another theory was that criminals had been stealing milk from the barn, or that locals had been illegally gambling there, and had somehow sparked it off. One newspaper declared that the fire had been started by juvenile delinquents who were surreptitiously smoking cigarettes in the barn; another paper, noting that a fire had broken out that same day in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, opined that a meteor had broken into pieces, with fragments falling to Earth and setting both towns ablaze.

But by far the most popular theory was that Kate O'Leary had been milking one of her cows (named, in various versions, "Daisy" or sometimes "Gwendolyne") when it kicked over a glass kerosene lantern and set fire to the barn. The story was based more on anti-immigrant and especially anti-Catholic Irish bigotry than on any real evidence, but it became so widely-accepted that Kate O'Leary (who always maintained that she had been in bed when the flames started) lived as a virtual recluse for the rest of her life, constantly rebuffing newspaper reporters who wanted to interview her.

"The Great Rebuilding" of Chicago began almost immediately, as aid flooded in from as far away as London. To prevent a repeat of the disaster, city officials mandated that all new buildings had to be constructed of fireproof materials like iron, stone, brick and terra cotta. But since much of the city was homeless and needed shelter quickly, authorities turned a blind eye when a mass of hasty wooden shanties appeared in the burned-out residential areas--until July 1874, when another fire broke out and destroyed 800 wooden buildings clustered together in 60 acres.

Comment: In July 1874, Chicago was once again the setting for another large fire that, in some areas, followed the same path as the Great Fire . . . For insurers, this was the last straw; they threatened a boycott, which forced the city to improve and strengthen its safety rules and its fire department [link].

After that, the new building codes were strictly enforced, and the unsafe wooden tenements were torn down. An entire new style of architecture appeared, consisting of plain unadorned masonry multi-story buildings that became known as the "Chicago School".

Over the years, as Chicago recovered, architects sought a new way to express the city's growth and grandeur. In 1884, when the New York Home Insurance Company moved to Chicago, the builders used a new material--steel girders--to make a light but strong framework that stretched into the sky, taller than any other building in the world. It became known as a "skyscraper". By the end of the century, builders in cities all over the globe were competing to make the world's tallest buildings, and "skyscrapers" reached 100 floors and more.

Today, the Chicago History Museum displays a collection of melted artifacts recovered from the Great Chicago Fire.

As bad as it was, it gave the city a chance to start over, this time with good planning. The debris was put in the lake to become Grant Park. The new city was laid out in a perfect grid with major streets every 4 blocks. To find a way somewhere, one only needs 2 coordinates; position north/south x position east/west.

It gets me thinking about the kind of world we can plan if we get to start over.