California is in the third year of one of the state's worst droughts in the past century, one that's led to fierce wildfires, water shortages and restrictions, and potentially staggering agricultural losses.

The dryness in California is only part of a longer-term, 15-year drought across most of the Western USA, one that bioclimatologist Park Williams said is notable because "more area in the West has persistently been in drought during the past 15 years than in any other 15-year period since the 1150s and 1160s" - that's more than 850 years ago.

"When considering the West as a whole, we are currently in the midst of a historically relevant megadrought," said Williams, a professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University in New York.

Megadroughts are what Cornell University scientist Toby Ault calls the "great white sharks of climate: powerful, dangerous and hard to detect before it's too late. They have happened in the past, and they are still out there, lurking in what is possible for the future, even without climate change." Ault goes so far as to call megadroughts "a threat to civilization."

What Is A Megadrought?

Megadroughts are defined more by their duration than their severity. They are extreme dry spells that can last for a decade or longer, according to research meteorologist Martin Hoerling of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Megadroughts have parched the West, including present-day California, long before Europeans settled the region in the 1800s.

Most of the USA's droughts of the past century, even the infamous 1930s Dust Bowl that forced migrations of Oklahomans and others from the Plains, "were exceeded in severity and duration multiple times by droughts during the preceding 2,000 years," the National Climate Assessment reported this year.

The difference now, of course, is the Western USA is home to more than 70 million people who weren't here for previous megadroughts. The implications are far more daunting.

Overall, "the nature of the beast is that drought is cyclical, and these long periods of drought have been commonplace in the past," according to Mark Svoboda, a climatologist at the National Drought Mitigation Center in Lincoln, Neb. "We are simply much more vulnerable today than at any time in the past. People can't just pick up and leave to the degree they did in the past."

Ault agrees that this long-term Western dry spell could be classified as a megadrought. "But this is not as bad as it could get," he warned.

How do scientists know how wet or dry it was centuries ago? Though no weather records exist before the late 1800s, scientists can examine paleoclimatic "proxy data," such as tree rings and lake sediment, to find out how much - or little - rain fell hundreds or even thousands of years ago.

At the most simplistic level, tree rings are wider during wet years and narrower during dry years.

"Prolonged droughts - some of which lasted more than a century - brought thriving civilizations, such as the ancestral Pueblo (Native Americans) of the Four Corners region, to starvation, migration and finally collapse, " Lynn Ingram, a geologist at the University of California-Berkeley, wrote in her recent book The West Without Water.

Ault says decade-long droughts happen once or twice a century in the Western USA, but much worse droughts, ones that last for multiple decades, occur once or twice per millennium.

Has California reached megadrought status? Not yet: "This one wouldn't stand out as a megadrought," Hoerling said. Even so, "this is the state's worst consecutive three years for precipitation in 119 years of records," he said.

As of Aug. 28, 100% of the state of California was considered to be in a drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. More than 58% is in "exceptional" drought, the worst level. Record warmth has fueled the drought as the state sees its hottest year since records began in 1895, the National Climatic Data Center reports.

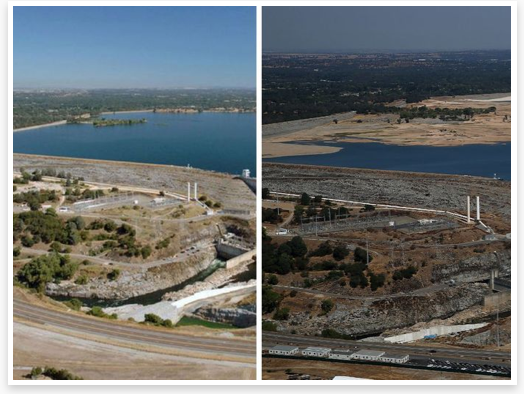

Because of the dryness, Calif. Gov. Jerry Brown declared a statewide drought emergency this year. Since then, reservoir storage levels have continued to drop, and as of late August, they were down to about 59% of the historical average.

Regulations restricting outdoor water use were put in place in late July for the entire state. People aren't allowed to hose down driveways and sidewalks, nor are they allowed to water lawns and landscapes (if there is excess runoff). There are reports of wells running dry in central California.

About 1,000 more wildfires than usual have charred the state, including some unusual ones in the spring.

Full water levels are visible behind the Folsom Dam at Folsom Lake on July 20, 2011, in Folsom, Calif. Low water levels are shown on Aug. 19 in Folsom, Calif. (Photo: Getty Images)

The drought is likely to inflict $2.2 billion in losses on the agricultural industry, according to a July study from the University of California-Davis.

How Bad Can It Get In California?

"If California suffered something like a multi-decade drought," University of Arizona climate scientist Gregg Garfin said, "the best-case scenario would be some combination of conservation, technological improvements (such as desalinization plants), multi-state cooperation on the drought, economic-based water transfers from agriculture to urban areas and other things like that to get humans through the drought.

"But there would be consequences for ecosystems and agriculture," he said.

"In the worst-case scenario, there might be out-migration and/or ghost towns," Garfin said. As a way to avoid this, "we could simply suck down more and more groundwater, which would have its own set of ramifications for local aquifers and the environment."

Even in the worst case of severe multi-decade drought, "it is hard for me to imagine people and businesses being banned from moving into urban areas of California," he said.

"We have much better resilience now than in the 'ghost town days,' with the ability to drill deeper, along with various ways of importing water and trading for water," Garfin said. "A more subtle way of restricting people (not banning them) is what Santa Fe has done - where new housing developments must either come with their own new source of water, or they must offset the water through conservation."

Overall, if the drought worsened, "we'd have to learn how to use water more efficiently," Ault said. "This is a glimpse of the future."

Role Of Climate Change

What role does climate change play in this drought or in future droughts?

Scientists such as Hoerling and Ault say they don't have the tools to tease out how much of this specific drought might be attributed to climate change.

"As of now, probably very little of the California drought can be attributed to climate change with any certainty," said tree-ring scientist Edward Cook of Lamont-Doherty.

Overall, past droughts have probably been due to subtle changes in water temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Cooler water temperatures - known as La Niñas - tend to produce drier conditions in the West.

Droughts in North America's "Medieval Warm Period" (roughly 950-1250) were associated with high temperatures in the Southwest and were probably caused by persistently cool La Niña-like conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Since 2000, the dominant climate pattern has been La Niña.

Hoerling noted that some computer models from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a United Nations science panel, show that California could actually see more, not less, winter rain and snow because of climate change.

However, overall rising temperatures would tend to favor more droughts, University of Arizona scientist Jonathan Overpeck said.

"It's been anomalously hot recently, which was not likely to have occurred without global warming," Overpeck said. "The odds are only going up that we could have a megadrought as the Earth warms."

Trends toward warmer temperatures could lead to a long-term dry spell in the region, according to a 2004 study led by Cook in the journal Science.

What's troubling is that the 20th century - during which time California's population increased from about 1.5 million to almost 40 million - may well have been an outlier, an unusually wet century: "Overall, the 20th century experienced less drought than most of the preceding four to 20 centuries," the Science study said.

Ault continues to investigate the relationship between climate change and megadroughts and the likelihood that an even more severe megadrought might hit in the next hundred years in the Southwest - one that's worse than any other drought in the past 1,000 years.

Specifically because of global warming, Ault says, the chances of the Southwestern USA experiencing a decade-long drought is at least 50% (but may be closer to 80%-90%), and the chances of a three-decade-long megadrought range from 20% to 50% over the next century. Ault is writing a study about this that will be published in a forthcoming issue of the American Meteorological Society's Journal of Climate.

"For the Southwestern U.S., I'm not optimistic about avoiding real megadroughts," Ault said. "As we add greenhouse gases into the atmosphere - and we haven't put the brakes on stopping this - we are weighting the dice for megadrought conditions.

"The risks would be lower if we didn't warm the planet as much as is expected to occur, but they aren't zero, because we know these things happen naturally," he said.

This is serious stuff: "Megadroughts are a threat to civilization," Ault said at an American Geophysical Union conference this year. "They could possibly be even worse than anything experienced by any humans who have lived in that part of the world for the last few thousand years."

Comment: Climate change is more likely due to Fireballs and Comets.

See also:

Climate Change Swindlers and the Political Agenda

Sott.net Series on Comets & Catastrophes