The discovery is important because it may help reveal the ethnic and cultural origins of some of history's first 'barbarians' - mountain tribes which had, in previous millennia, preyed on the world's first great civilizations, the cultures of early Mesopotamia in what is now Iraq.

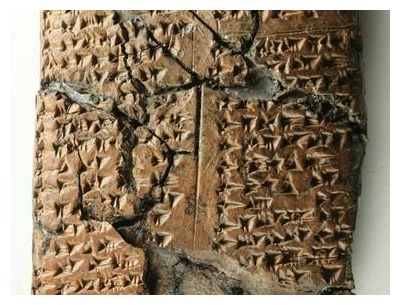

Evidence of the long-lost language - probably spoken by a hitherto unknown people from the Zagros Mountains of western Iran - was found by a Cambridge University archaeologist as he deciphered an ancient clay writing tablet unearthed by an international archaeological team excavating an Assyrian imperial governors' palace in the ancient city of Tushan, south-east Turkey.

The tablet revealed the names of 60 women - probably prisoners-of-war or victims of an Assyrian forced population transfer program. But when the Cambridge archaeologist - Dr. John MacGinnis - began to examine the names in detail, he realized that 45 of them bore no resemblance to any of the thousands of ancient Middle Eastern names already known to scholars.

Because ancient Middle Eastern names are normally composites, made-up, in full or abbreviated form, of ordinary words in the relevant local lexicon, the unique nature of the tablet's 45 mystery names is seen by scholars as evidence of a previously unknown language.

The clay tablet text originally formed part of the palace's archive - used by local Assyrian imperial officials to record their administrative, political and economic decisions and actions.

The 60 women (including the 45 with evidence of the previously unattested language) were almost certainly being deployed by the palace authorities for some economic purpose (potentially a female-associated craft activity like weaving). Indeed the text mentions that some of them were being allocated to specific local villages.

Typical names, born by the women - the evidence for the lost language - include Ushimanay, Alagahnia, Irsakinna and Bisoonoomay.

Now archaeologists and linguistics experts are set to analyse the mystery names in even greater details to try to discover whether the letter-order or letter frequency shows any similarities to previously attested ancient tongues to which this mystery language could be related.

The 45 women are thought to come from somewhere in the central or northern Zagros Mountains - because that is the only area in which the Assyrians were militarily active at the relevant time where the ancient languages are still largely unknown.

It's likely that the women were compulsorily moved from their Zagros Mountains homeland and assigned to work near Tushan sometime in the second half of the 8th century BC - probably as a result of conquests carried out in the Zagros by the Assyrian kings Tiglath Pilasser III or Sargon.

The excavation of the palace at Tushan is being carried out by a German archaeological team directed by Dr. Dirk Wicke of Mainz University as part of an archaeological investigation into the ancient Assyrian city led by Professor Timothy Matney of the University of Akron in Ohio. Full details about the discovery of the mystery names are published in the current issue of the Journal of Near Eastern Studies.

"The 60 women (including the 45 with evidence of the previously unattested language) were almost certainly being deployed by the palace authorities for some economic purpose (potentially a It's likely that the women were compulsorily moved from their Zagros Mountains homeland and assigned to work near Tushan sometime in the second half of the 8th century BC - probably as a result of conquests carried out in the Zagros by the Assyrian kings Tiglath Pilasser III or Sargon. like weaving). Indeed the text mentions that some of them were being allocated to specific local villages.

//snip//

It's likely that the women were compulsorily moved from their Zagros Mountains homeland and assigned to work near Tushan sometime in the second half of the 8th century BC - probably as a result of conquests carried out in the Zagros by the Assyrian kings Tiglath Pilasser III or Sargon."

Yeah, sure, weaving. The empire was short of weavers, so women were captured and carted away to the empire to work in the garment districts.

Another possible "female-associated craft activity" comes to mind.