|

| ©Wired |

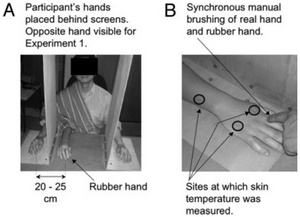

During the illusion, a participant's hand is hidden, and a rubber hand positioned so that it appears as her own. She knows that it's fake -- but when both hands are stroked simultaneously, what's seen and felt becomes blurred.

Suddenly the rubber hand literally feels like it belongs to her. Consciously she knows it's not true, but that doesn't matter. Threaten the fake hand, and people under the illusion's spell respond as if their own hands were threatened.

Scientists have now shown that the hidden hand's temperature drops during the illusion: its effects aren't simply mental, but physical as well, and could even hint at as-yet-unknown processes of disease.

"These findings show that the conscious sense of our physical self, and the physiological regulation of our physical self, are linked," write a team of researchers led by Oxford University's G. Lorimer Mosely and Charles Spence. "In fact, our results suggest that the conscious sense of our physical self may actually contribute to its homeostatic regulation."

At first, this may seem a retelling of mind-body linkage: embarrassment causes blushing, fear a burst of strength. But unlike those examples, these findings, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, connect the body and awareness of the body.

When participants in the study confused a rubber hand for their own, their hidden hands became half a degree colder. The effect was even more pronounced among people especially prone to the illusion.

Localized body temperature malfunctions have been also been observed in people with schizophrenia, self-injuring tendencies or peripheral nerve damage. Such conditions have always been linked to central nervous sytem damage, write the researchers, but findings suggest a possible role for cognitive malfunctions.

"It does seem like there are these connections, broadly speaking, between awareness and physiological changes," said Stephen Mitroff, a Duke University cognitive neuroscience who was not involved in the study. "Any time you can use illusion to tease apart what's happening in non-illusory situations, it could tell you about what's happening. It may be that they're starting us down the path of looking at these other issues. If this can help, that would be great."

Psychologically induced cooling of a specific body part caused by the illusory ownership of an artificial counterpart [PNAS]

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter