At stake is what to make of the funny, sexual, scary and just plain bizarre mental scenarios that play themselves out in our heads while we sleep. Are our subconsious fantasies coming up for a breath of air, as Sigmund Freud believed?

Is our brain consolidating lessons learned and pitching out unneeded data, as neuroscientists suggest? Or are dreams no more meaningful than a spontaneous run of erratic heartbeats, a hot flash, or the frisson we feel at the sight of an attractive passer-by?

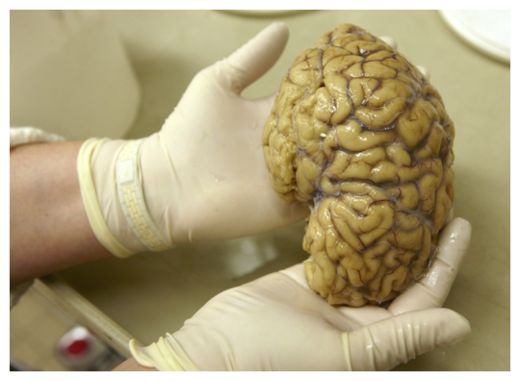

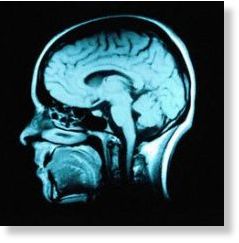

A study published this week in the journal Brain suggests that the impulse to dream may be little more than a tickle sent up from the brainstem to the brain's sensory cortex.

The full dream experience -- the complex scenarios, the feelings of fear, delight or longing -- may require the further input of the brain's higher-order cortical areas, the new research suggests. But even people with grievous injury to the brain's prime motivational machinery are capable of dreams, the study found.

The latest research looked for sleep-time "mentation" -- thoughts, essentially -- in a small group of very unusual patients. These patients -- 13 in all -- had suffered damage within their brains' limbic system, the seat of our basic desires and motivations -- for sex, for food, for pleasurable sensations brought on by drugs and friendship and whatever else turns us on.

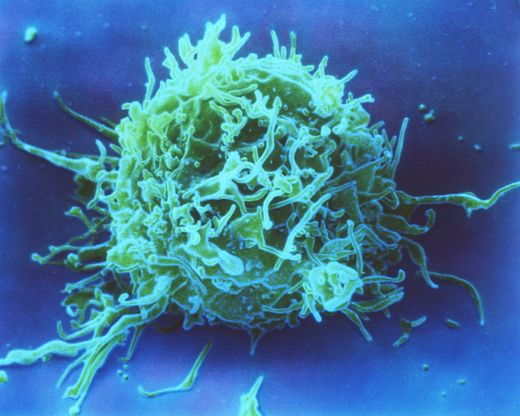

Comment: An amazing therapeutic tool that Big Pharma will most likely exploit with drugs that have more side effects than potential benefit. For a more natural way to balance up your immune system and your brain potential, visit our forum discussion

"Life Without Bread" and our Éiriú Eolas relaxation program.