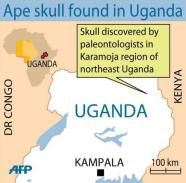

"This is the first time that the complete skull of an ape of this age has been found ... it is a highly important fossil and it will certainly put Uganda on the map in terms of the scientific world," Martin Pickford, a paleontologist from the College de France in Paris, told journalists in Kampala.

The fossilised skull belonged to a male Ugandapitchecus Major, a remote cousin of today's great apes which roamed the region around 20 million years ago.

The team discovered the remains on July 18 while looking for fossils in the remants of an extinct volcano in Uganda's remote northeastern Karamoja region.

Preliminary studies of the fossil showed that the tree-climbing herbivore, roughly 10 years old when it died, had a head the size of a chimpanzees but a brain the size of a baboons, Pickford said.