A team of scholars has discovered what might be the oldest representation of the Tower of Babel of Biblical fame, they report in a newly published book.

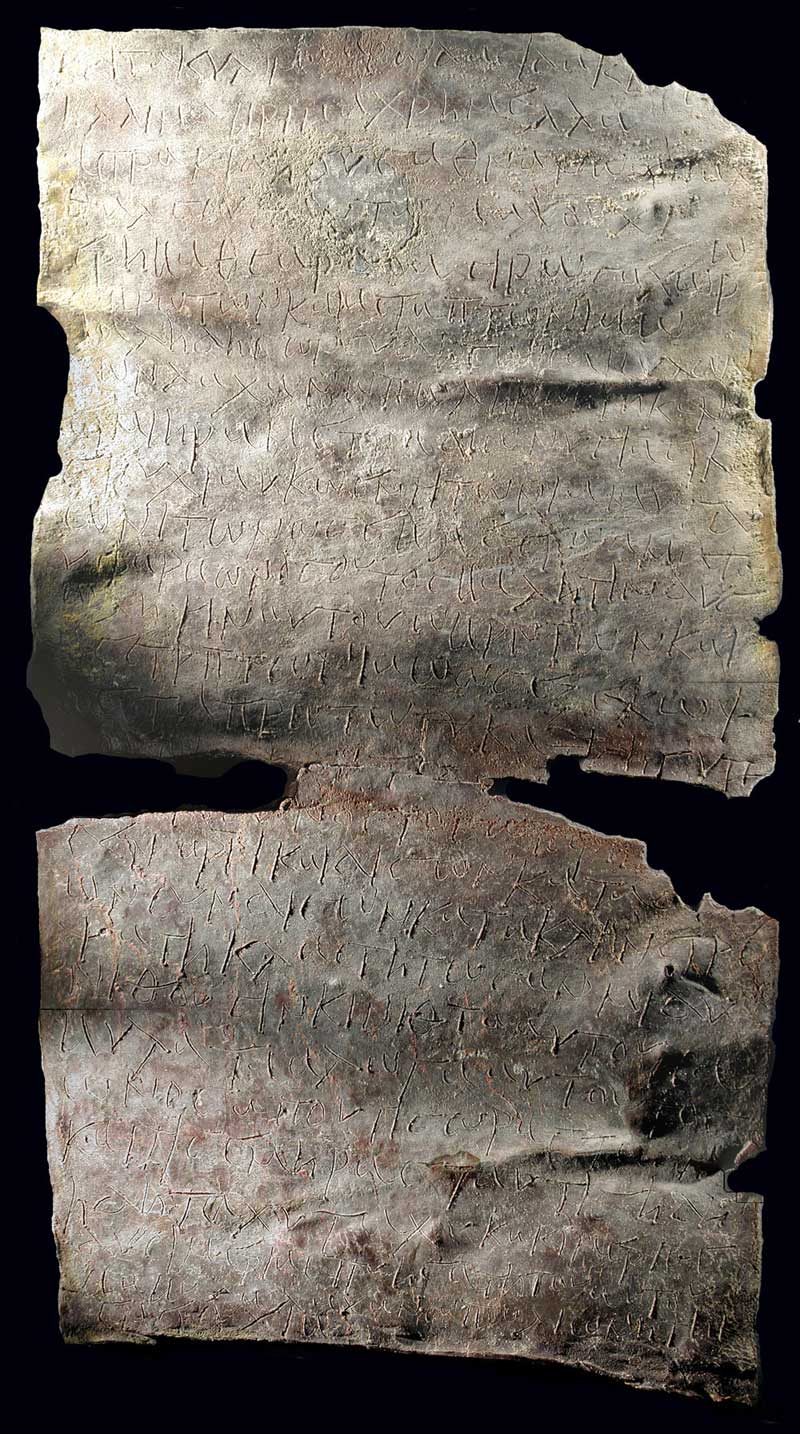

Carved on a black stone, which has already been dubbed the Tower of Babel stele, the inscription dates to 604-562 BCE.

It was found in the collection of Martin Schøyen, a businessman from Norway who owns the largest private manuscript assemblage formed in the 20th century.

Consisting of 13,717 manuscript items spanning over 5,000 years, the collection includes parts of the Dead Sea Scrolls, ancient Buddhist manuscript rescued from the Taliban, and even cylcon symbols by Australia's Aborigines which can be up to 20,000 years old.

The collection also includes a large number of pictographic and cuneiform tablets -- which are some of the earliest known written documents -- seals and royal inscription spanning most of the written history of Mesopotamia, an area near modern Iraq.

A total of 107 cuneiform texts dating from the Uruk period about 5,000 years ago to the Persian period about 2,400 years ago, have been now translated by an international group of scholars and published in the book Cuneiform Royal Inscriptions and Related Texts in the Schøyen Collection.

The Tower of Babel stele stands out as one of "the stars in the firmament of the book," wrote Andrew George, a professor of Babylonian at the University of London and editor of the book.

The spectacular stone monument clearly shows the Tower and King Nebuchadnezzar II, who ruled Babylon some 2,500 years ago.