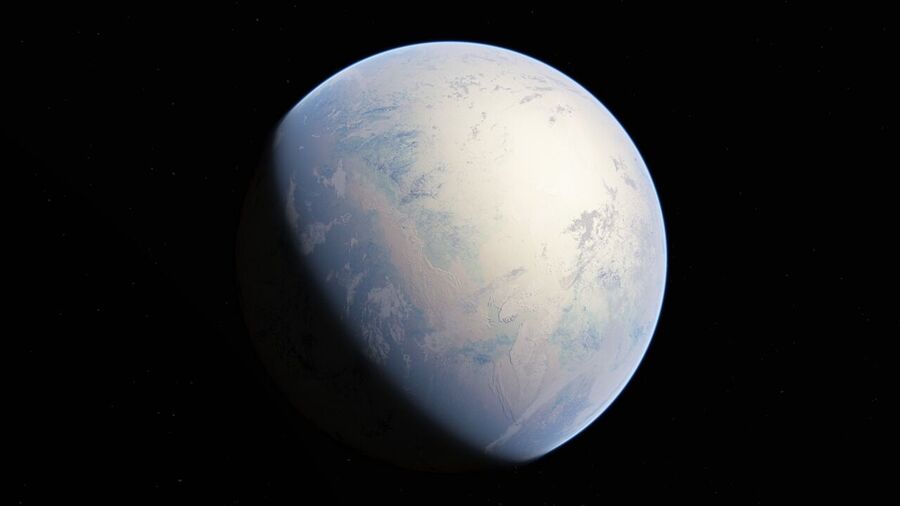

According to a new study, these so-called "Snowball" Earth periods, in which the planet's surface was covered in ice for thousands or even millions of years, could have been triggered abruptly by large asteroids that slammed into the Earth.

The findings, detailed in the journal Science Advances, may answer a question that has stumped scientists for decades about some of the most dramatic known climate shifts in Earth's history. In addition to Yale, the study included researchers from the University of Chicago and the University of Vienna.

Climate modelers have known since the 1960s that if the Earth became sufficiently cold, the high reflectivity of its snow and ice could create a "runaway" feedback loop that would create more sea ice and colder temperatures until the planet was covered in ice. Such conditions occurred at least twice during Earth's Neoproterozoic era, 720 to 635 million years ago.

Yet efforts to explain what initiated these periods of global glaciation, which have come to be known as "Snowball Earth" events, have been inconclusive. Most theories have centered on the notion that greenhouse gases in the atmosphere somehow declined to a point where "snowballing" began.

Comment: Which highlights how greenhouse gasses pale in comparison to the real drivers of climate.

"We decided to explore an alternative possibility," said lead author Minmin Fu, the Richard Foster Flint Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences in Yale's Faculty of Arts and Sciences. "What if an extraterrestrial impact caused this climate change transition very abruptly?"

For the study, the researchers used a sophisticated climate model that represents atmospheric and ocean circulation, as well as the formation of sea ice, under different conditions. It is the same type of climate model that is used to predict future climate scenarios.

In this instance, the researchers applied their model to the aftermath of a hypothetical asteroid strike in four distinct periods of the past: preindustrial (150 years ago), Last Glacial Maximum (21,000 years ago), Cretaceous (145 to 66 million years ago), and Neoproterozoic (1 billion to 542 million years ago).

For two of the warmer climate scenarios (Cretaceous and preindustrial), the researchers found that it was unlikely that an asteroid strike could trigger global glaciation. But for the Last Glacial Maximum and Neoproterozoic scenarios, when the Earth's temperature may have been already cold enough to be considered an ice age — an asteroid strike could have tipped Earth into a "Snowball" state.

"What surprised me most in our results is that, given sufficiently cold initial climate conditions, a 'Snowball' state after an asteroid impact can develop over the global ocean in a matter of just one decade," said co-author Alexey Fedorov, a professor of ocean and atmospheric sciences in Yale's Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

Comment: Bearing in mind these models aren't factoring in the contribution that cometary dust loading, increased volcanic activity, and a grand solar minimum, can have on conditions, because if they had, they might discover that this combination may have also contributed to even the 'Little Ice Age' just several hundred years ago; and all phenomena that we're also seeing on the increase today: Little Ice Age triggered by unusually warm period, unprecedented cold struck within 20 years

"By then the thickness of sea ice at the Equator would reach about 10 meters. This should be compared to a typical sea ice thickness of one to three meters in the modern Arctic."

As for the chances of an asteroid-induced "Snowball Earth" period in the years to come, the researchers said it was unlikely — due in part to human-caused warming that has heated the planet — even though other impacts could be as devastating.

Comment: As noted in the link above, a period of warming often precedes the cooling.

The research was supported by the Flint Postdoctoral Fellowship at Yale and the ARCHANGE project. Co-authors of the study are Dorian Abbot of the University of Chicago and Christian Koeberl of the University of Vienna.

It was hard to take anything in the article seriously after that point. We know how accurate those are.