Ponerology is about how human nature goes wrong. As rough categories, Lobaczewski divides humanity into two broad groups: normal (around 90% of the population) and ponerogenic/psychopathological (10%, give or take).1 Of course, the boundaries between the two are fuzzy, the one shading imperceptibly over into the other, until the difference becomes so obvious that we see why we have the categories in the first place.2 This is the realm of the dangerous personality disorders — highly heritable constellations of cognitive-affective-behavioral dysfunction.

But this post will not be on that 10%. Rather it will be on the problems with the 90%: the features of normal humanity that when out of control edge over into psychopathology, and which contribute to ponerogenesis. Lobaczewski lists a few of these problem areas: the "egotism of the natural worldview," conversive/dissociative thinking, and moralizing about psychobiology.3

In the notes to Political Ponerology I made the connection between what Lobaczewski calls conversive thinking and what we call cognitive biases. An interesting paper was published earlier this year that makes the connections even clearer: "Toward Parsimony in Bias Research: A Proposed Common Framework of Belief-Consistent Information Processing for a Set of Biases," by Aileen Oeberst and Roland Imhoff. Here's the abstract:

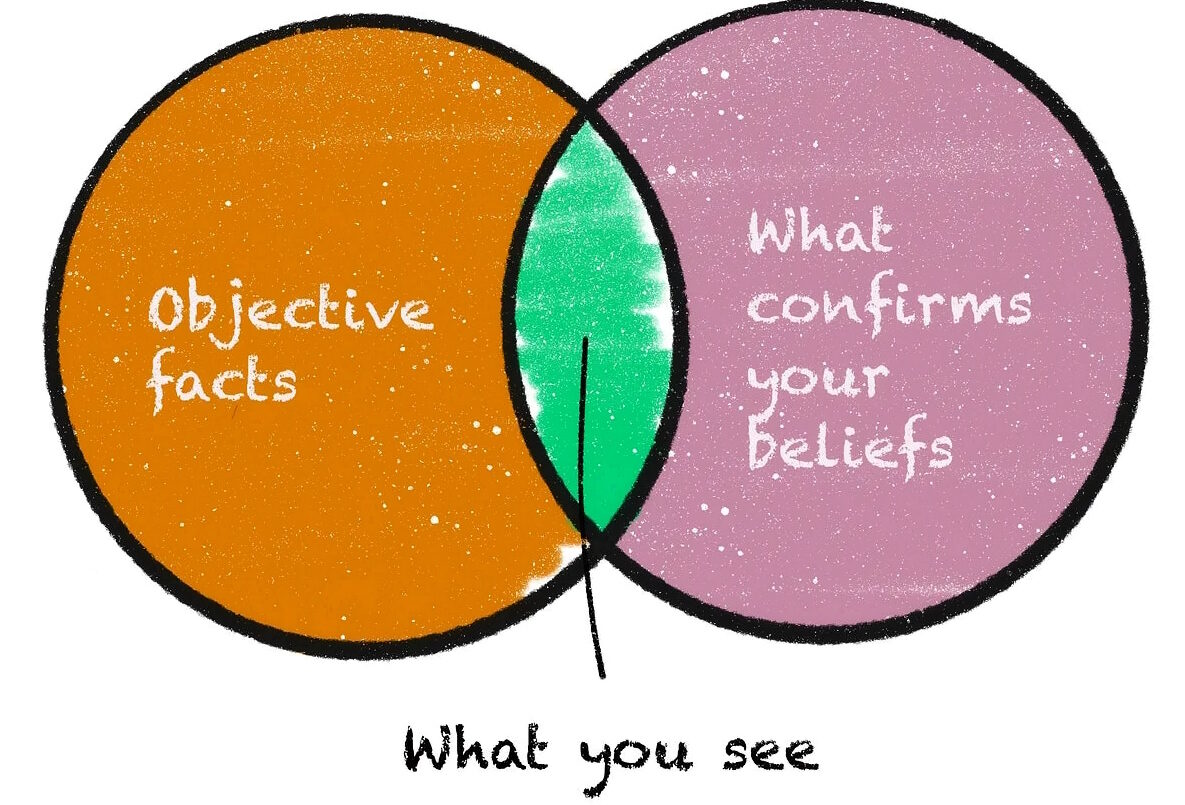

One of the essential insights from psychological research is that people's information processing is often biased. By now, a number of different biases have been identified and empirically demonstrated. Unfortunately, however, these biases have often been examined in separate lines of research, thereby precluding the recognition of shared principles. Here we argue that several — so far mostly unrelated — biases (e.g., bias blind spot, hostile media bias, egocentric/ethnocentric bias, outcome bias) can be traced back to the combination of a fundamental prior belief and humans' tendency toward belief-consistent information processing. What varies between different biases is essentially the specific belief that guides information processing. More importantly, we propose that different biases even share the same underlying belief and differ only in the specific outcome of information processing that is assessed (i.e., the dependent variable), thus tapping into different manifestations of the same latent information processing. In other words, we propose for discussion a model that suffices to explain several different biases. We thereby suggest a more parsimonious approach compared with current theoretical explanations of these biases. We also generate novel hypotheses that follow directly from the integrative nature of our perspective.In other words, humans have a "systematic tendency toward belief-consistent information processing" (e.g. confirmation bias), and when this is combined with certain beliefs we get a number of biases. Or, in Lobaczewski's language, biases can be understood as the combination of a natural worldview plus conversive thinking, all of which together contribute to the egotism of the natural worldview. Here's how the authors describe this egotism:

In sum, belief-consistent information processing seems to be a fundamental principle in human information processing that is not only ubiquitous ... but also a conditio humana. ... belief-consistent information processing takes place even when people are not motivated to confirm their belief. Furthermore, belief-consistent information processing has been shown even when people are motivated to be unbiased..., or at least want to appear unbiased. ... even when a judgment or task is about another person, people start from their own lived experience and project it — at least partly — onto others as well ...

Taken together, a number of biases seem to result from people taking — by default — their own phenomenology as a reference in information processing ... Put differently, people seem to — implicitly or explicitly — regard their own experience as a reasonable starting point when it comes to judgments about others and fail to adjust sufficiently. This is how Lobaczewski described the egotism of the natural worldview:

... we often meet with sensible people endowed with a well-developed natural worldview as regards psychological, societal, and moral aspects, frequently refined via literary influences, religious deliberations, and philosophical reflections. Such persons have a pronounced tendency to overrate the value of their worldview, behaving as though it were an objective basis for judging other people. They do not take into account the fact that such a system of apprehending human matters can also be erroneous, since it is insufficiently objective. (Political Ponerology, p. 21)In the context of ponerology, people take their own frame of reference — which usually by default does not include much if any information about psychopathology — and assume it is the gold standard for understanding the world in general, and ponerogenic phenomena in particular. By closing themselves off from a ponerological understanding, they close themselves off from effectives means for dealing with evil in their lives and in the world at large.

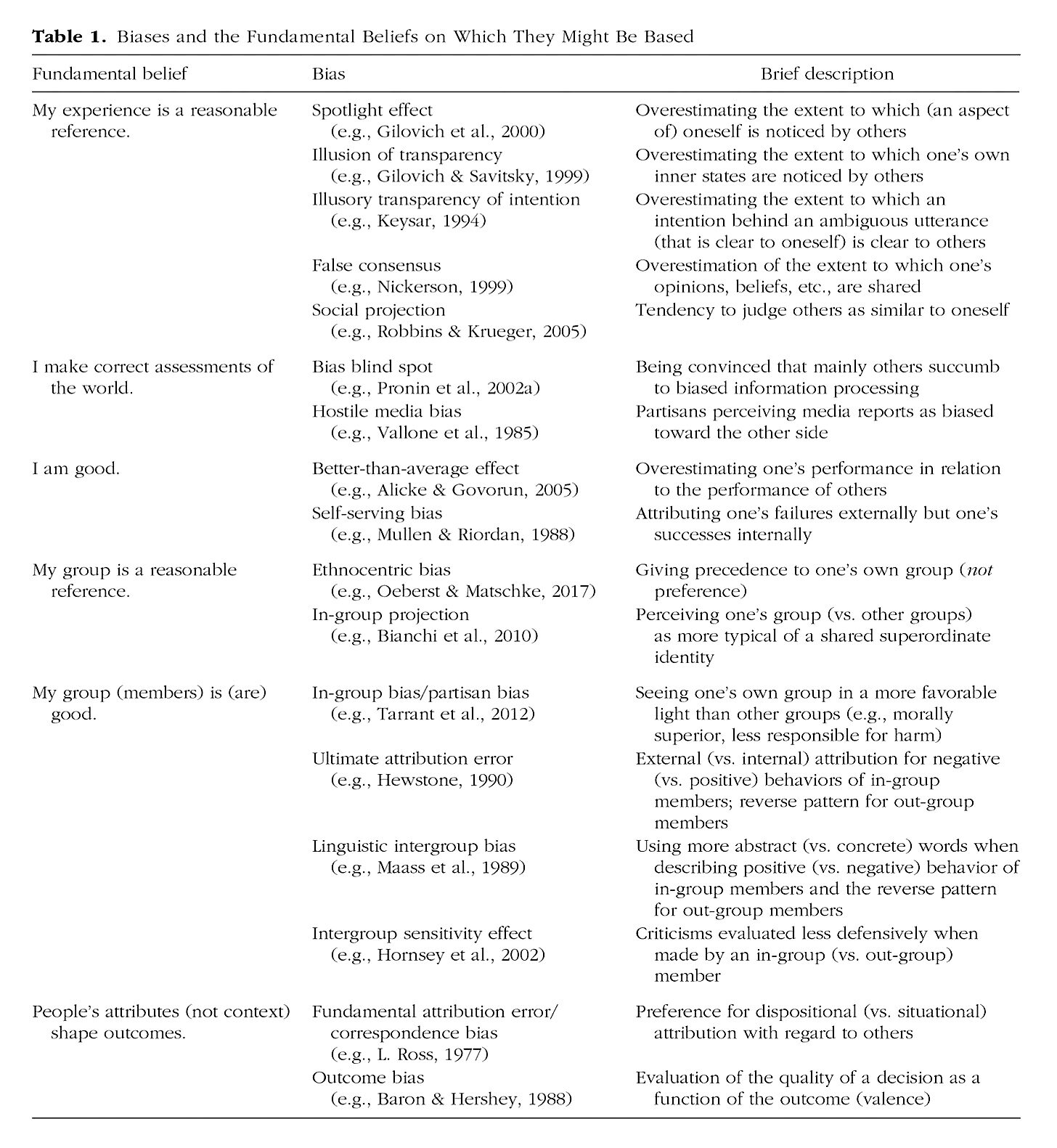

Now, here is how the paper's authors group some common biases, and the fundamental beliefs inspiring them:

The beliefs in the left column make up a decent summary of the "natural worldview": "my experience is a reasonable reference, I make correct assessments of the world, I am good, my group is a reasonable reference, my group is good, people's attributes (not context) shape outcomes."

That's not to say that our cognition is fundamentally and irremediably flawed, however. There's an argument to be made that biases and heuristics in general are fundamentally rational and adaptive. For instance, Oeberst and Imhoff write:

... it has been argued that many biases and heuristics could be regarded as rational in the context of real-world settings, in which people lack complete knowledge and have an imperfect memory as well as limited capacities ... In the same context, researchers have argued that some of the heuristics lead to biases mainly in specific lab tasks while resulting in rather accurate judgments in many real-world situations ... In other words, they argued for the adaptivity of these heuristics, which are mostly correct, whereas research focuses on the few (artificial) situations in which they lead to incorrect results (i.e., biases).In other words, there is the possibility that the beliefs listed are useful in some ways, maybe even in general, but only lead to detrimental error (bias) in certain circumstances. Lobaczewski calls this phenomenon the "para-adequate" or "para-adaptive" response — a tendency that works on the whole, but only fails in circumstances for which it wasn't designed. In the context of ponerology, such circumstances are those having to do with ponerogenic phenomena. For instance, the tendency to trust or offer help to a stranger may be healthy in most cases, but potentially fatal in the case of an encounter with a psychopath.

Additionally, the beliefs themselves may even be justified, to a degree. For example:

Taken together, due to a number of reasons people overwhelmingly perceive themselves as making correct assessments. Be it because they are correct, or because they are simply not corrected. Such an overgeneralization to a fundamental belief of making correct assessments could, thus, actually be regarded as a reasonable extrapolation.More broadly, however, these biases cause us to misread reality in particular ways. As Lobaczewski put it above, "such a system of apprehending human matters can also be erroneous, since it is insufficiently objective." Partly this has to do with being motivated to avoid uncomfortable feelings. From the paper:

... research has repeatedly affirmed people's tendency to be intolerant of ambiguity and uncertainty and found a preference for "cognitive closure" (i.e., a made-up mind) instead ...But as the authors note, the tendency to seek confirming information is even more fundamental than that:

... in some beliefs, people may have already invested a lot (e.g., one's beliefs about the optimal parenting style or about God/paradise...) so that the beliefs are psychologically extremely costly to give up (e.g., ideologies/political systems one has supported for a long time...).

... individuals tend to scan the environment for features more likely under the hypothesis (i.e., belief) than under the alternative ("positive testing"...). People also choose belief-consistent information over belief-inconsistent information ("selective exposure" or "congeniality bias"...). They tend to erroneously perceive new information as confirming their own prior beliefs ("biased assimilation"...; "evaluation bias"...) and to discredit information that is inconsistent with prior beliefs ("motivated skepticism" ... "disconfirmation bias" ... "partisan bias"...). At the same time, people tend to stick to their beliefs despite contrary evidence ("belief perseverance"...), which, in turn, may be explained and complemented by other lines of research. "Subtyping," for instance, allows for holding on to a belief by categorizing belief-inconsistent information into an extra category (e.g., "exceptions"...). Likewise, the application of differential evaluation criteria to belief-consistent and belief-inconsistent information systematically fosters "belief perseverance" ... Partly, people hold even stronger beliefs after facing disconfirming evidence ("belief-disconfirmation effect"...).This is also how Lobaczewski categorizes conversive thinking: it can take place at various progressively deeper levels of information processing. For example, one can simply block out a disconfirming conclusion, select only those data confirming the already held belief (and delete from awareness the offending data), or substitute data (reconstruct it) in a form that confirms the belief.

... belief-consistent information processing emerges at all stages of information processing such as attention..., perception..., evaluation of information..., reconstruction of information..., and the search for new information... — including one's own elicitation of what is searched for ("self-fulfilling prophecy"...). Moreover, many stages (e.g., evaluation) allow for applying various strategies (e.g., ignoring, underweighting, discrediting, reframing).

When people selectively attend to or search for belief-consistent information (positive testing, selective exposure, congeniality bias), when they selectively reconstruct belief-consistent information from their memory, and when they behave in a way such that they elicit the phenomenon they searched for themselves (self-fulfilling prophecy), they already display bias ... People are biased in eliciting new data, and those data are then processed; people do not simply update their beliefs on the basis of information they (more or less arbitrarily) encounter in the world. As a result, people likely gather a biased subsample of information, which, in turn, will not only lead to biased prior beliefs but may also lead to strong beliefs that are actually based on rather little (and entirely homogeneous) information. But there are even more and more extreme ways in which prior beliefs may bias information processing: Prior beliefs may, for instance, affect whether or not a piece of information is regarded as informative at all for one's beliefs ... Categorizing belief-inconsistent information into an extra class of exceptions (that are implicitly uninformative to the hypothesis) is such an example (or subtyping...). Likewise, discrediting a source of information easily legitimates the neglect of information (see disconfirmation bias). In its most extreme form, however, prior beliefs may not be put to a test at all. Instead, people may treat them as facts or definite knowledge, which may lead people to ignore all further information or to classify belief-inconsistent information simply as false.

When our map of reality is corrupted, we cannot navigate reality. And if that map is of the landscape of evil surrounding us, we will not be able to deal with it effectively.

To make matters worse, psychopaths are aware of this on an almost instinctive level. A lifetime of observing "normies" and their weaknesses makes them expert manipulators. The authors give an example of one of these easily exploited tendencies:

... once a society decided to hold a person captive because of the potential danger that emanates from the person, there is no chance to realize the person was not dangerous.The psychopath is an excellent slanderer and character assassin. Strike first, and the stink is almost impossible to remove.

But is the situation hopeless? Lobaczewski didn't think so. He wrote:

There is no such thing as a person whose perfect self-knowledge allows him to eliminate all tendencies toward conversive thinking, but some people are relatively close to this state, while others remain slaves to these processes. (p. 144)His recommendations:

We should point out that the erroneous thought processes described herein also, as a rule, violate the laws of logic with characteristic treachery. Educating people in the art of proper reasoning can thus serve to counteract such tendencies; it has a hallowed age-old tradition, though for centuries it has proven insufficiently effective. ... An effective measure would be to teach both principles of logic and skillful detection of errors in reasoning — including conversive errors. The broader front of such education should be expanded to include psychology, psychopathology, and the science described herein [i.e. ponerology], for the purpose of raising people who can easily detect any paralogism. (pp. 145-146)Here is what the paper's authors have to say on the possible prospects for such education. The picture isn't as optimistic as Lobaczewski thinks, but there is hope:

... knowledge about the specific bias, the availability of resources (e.g., time), as well as the motivation to deliberate are considered to be necessary and sufficient preconditions to effectively counter bias according to some models ... Although this might be true for logical problems that suggest an immediate (but wrong) solution to participants (e.g., "strategy-based" errors...), much research attests to people's failure to correct for biases even if they are aware of the problem, urged or motivated to avoid them, and are provided with the necessary opportunity ...The authors end their paper with some additional hypotheses derived from their framework. For instance, they hypothesize a fundamental belief (that one makes correct assessments) that "might be regarded as a kind of 'g factor' of biases." This would result in a natural variation, hinted at by Lobaczewski above:

... avoidance of biases might need a specific form of deliberation. Interestingly, much research shows that there is an effective strategy for reducing many biases: to challenge one's current perspective by actively searching for and generating arguments against it ("consider the opposite"...). This strategy has proven effective for a number of different biases such as confirmation bias..., the "anchoring effect"..., and the hindsight bias ... At least in part, it even seems to be the only effective countermeasure ... Essentially, this is another argument for the general reasoning of this article, namely that biases are based on the same general process — belief-consistent information processing. Consequently, it is not the amount of deliberation that should matter but rather its direction. Only if people tackle the beliefs that guide — and bias — their information processing and systematically challenge them by deliberately searching for belief-inconsistent information, we should observe a significant reduction in biases — or possibly even an unbiased perspective. From the perspective of our framework, we would thus derive the hypothesis that the listed biases could be reduced (or even eliminated) when people deliberately considered the opposite of the proposed underlying fundamental belief by explicitly searching for information that is inconsistent with the proposed underlying belief.

Following from this, we expect natural (e.g., interindividual) or experimentally induced differences in the belief of making correct assessments (e.g., undermining it [e.g. gaslighting]...) to be mirrored not only in biases based on this but also other beliefs (H3).This suggests that confirming another belief will also confirm this fundamental belief, in a string of conversive logic.

For example, people who believe their group to be good and engage in belief-consistent information processing leading them to conclusions that confirm their belief are at the same time confirmed in their convictions that they make correct assessments of the world. The same should work for other biases such as the "better-than-average effect" or "outcome bias," for instance. If I believe myself to be better than the average, for instance, and subsequently engage in confirmatory information processing by comparing myself with others who have lower abilities in the particular domain in question, this should strengthen my belief that I generally assess the world correctly.Incidentally, I think this is why smart people can be insufferable. Not only are they often right, they also seek out situations where that will be the case, thus strengthening their own egotism, which then piggybacks itself into areas in which they are dead wrong. But being human, they will hold those beliefs as strongly as the ones that are actually justified. This is "danger-zone" intelligence.

There is one exception, however. If one was aware that one is processing information in a biased way and was unable to rationalize this proceeding, biases should not be expressed because it would threaten one's belief in making correct assessments. In other words, the belief in making correct assessments should constrain biases based on other beliefs because people are rather motivated to maintain an illusion of objectivity regarding the manner in which they derived their inferences ... Thus, there is a constraint on motivated information processing: People need to be able to justify their conclusions ... If people were stripped of this possibility, that is, if they were not able to justify their biased information processing (e.g., because they are made aware of their potential bias and fear that others could become aware of it as well), we should observe attempts to reduce that particular bias and an effective reduction if people knew how to correct for it (H5).I recommend reading the whole paper if you found these excerpts interesting. There are many more examples, and who knows, just reading it might make us all a little less egotistical.

Harrison Koehli co-hosts SOTT Radio Network's MindMatters, and is an editor for Red Pill Press. He has been interviewed on several North American radio shows about his writings on the study of ponerology. In addition to music and books, Harrison enjoys tobacco and bacon (often at the same time) and dislikes cell phones, vegetables, and fascists (commies too).Notes:

- Note that by "psychopathological" he's not referring to the things we ordinarily associate with the word: e.g. depression and anxiety. He's specifically referring to what he calls "ponerogenic factors," which are the specific pathologies most associated with evil, e.g., personality disorders and character-deforming brain damage.

- E.g., the difference between "Man, that was kind of a douchey thing to do" and "This guy is literally Satan."

- The implicit message of this last one (which won't be a focus of this article) is that moralizing should be reserved for normal people; ponerogenic factors should be treated dispassionately.

Who wants to be a normy?