© GettyA protester clashes with police during a commemoration march for Nahel Merzouk last week.

In the spring of 1775 a wave of riots, approximately 300 in total, engulfed the Kingdom of France. The protests did not subside until the army had been deployed and hundreds of rioters arrested. These events became known as the

"Flour War" because the riots were precipitated by a sharp increase in grain prices, which were then passed on to French consumers in the form of higher food prices.

While the Flour War seems like ancient history, it may well have something to tell us about the

riots taking place in France over the last few days. Of course, the immediate cause of this unrest was the shooting of a teenager by police. Yet it

follows on from smaller riots this year, first in

response to President Emmanuel Macron's pension reforms, and then to the

building of reservoirs in the west of the country.

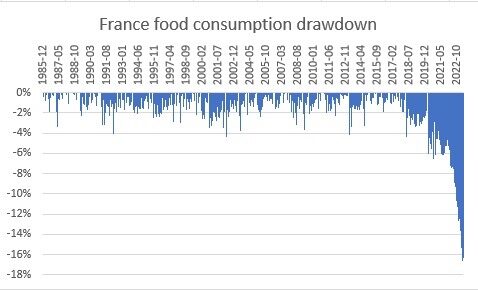

It is hard to escape the obvious conclusion: these riots, all set off by different immediate causes, point to underlying discontent in the French population. One does not have to look very hard to find it. Just as in 1775, French food prices are increasing, with a 22% rise since 2021. And that's before considering France's still-high energy prices.The result of these rising costs has been a decline in French food consumption of nearly 17%, the largest such national decline since the data started in the early 1980s. Up until now, drawdowns — that is, peak-to-trough declines — in food consumption have never exceeded 4%. And even when they hit this level, they quickly reverted.Today, however, we are seeing persistent and historically unprecedented drawdowns in the country's food consumption. Indeed, modern France has never experienced this sort of hit to its basic living standards.

© INSEE

Naturally, declines in food consumption hit the poorest harder.

Research shows that people with higher incomes spend significantly lower proportions of their incomes on food than those who earn less. People in the top 25% of incomes spend around 7.6% of their income on food, while those in the bottom quarter spend over 30%. It is this latter group which accounts for much of the fall in food consumption.

The French figures align with the data we have in Britain. A recent survey showed that one in seven Britons are skipping meals due to rising food prices. A survey in France revealed that 57% of people have reduced their consumption of meat — notable in a culture with a particularly carnivorous diet.What is the cause of rising food prices?

Most likely, the finger can be pointed at fertiliser shortages. The World Economic Forum

notes that Russia and Belarus are among the world's largest sources of mineral fertilisers. When the West undertook sanctions against Russia, it tried to create carve-outs for some fertiliser products, but the red tape has meant that imports have fallen precipitously, while fertiliser prices have spiked. Hence the rising cost of food.

It is these dynamics that are creating the febrile situation we see across Europe today. France has a history of social unrest, and its ethnic tensions are starker than those found elsewhere in Europe. But the more things change, the more they stay the same. Rising food prices and falling food consumption are still an extremely effective predictor of riots and social unrest.

Yeah right, had nothing to due with importing hoards of ORKS bred for the purpose of starting riots and destroying everything around them, what the fuck they didn't build it. The same fucking tribe that controls it, ASSHOLE.