© Getty

Just under one in eight of all households in England were found to be fuel-poor in 2022. Now in 2023 the true impact of the

energy crisis over the past 12 months has been revealed with the release of shocking new statistics.

Express.co.uk has analysed the harrowing picture of fuel poverty in England.

Britons paid more in household energy bills in 2022 than any other year in history, with the ensuing cost-of-living crisis stretching budgets to and beyond breaking point for many.

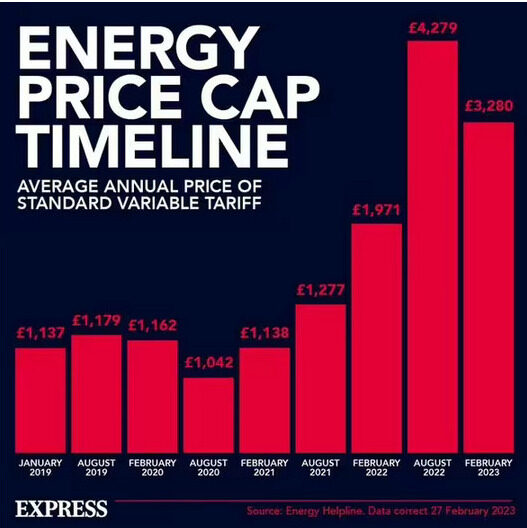

After

four consecutive rises since February 2021, the state energy regulator Ofgem had the price cap set at £4,279 by the end of the year - over

triple the average annual bill just three years earlier.

On Monday, Ofgem announced that from April 1,

the price cap would fall by almost £1,000 to £3,280 -but with a £500 increase to the Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) scheduled at the same time, the pain of the last year is likely to endure for many throughout 2023.

The Ofgem price cap will begin to fall in 2023

A report released by the Department for Energy Security & Net Zero on Tuesday shows

3.26 million households in England were in fuel poverty in 2022 - 13.4 percent of the total.Fuel poverty describes

the condition by which a household cannot afford to keep their home at an adequate temperature, according to the End Fuel Poverty Coalition. This can be caused by low incomes, unaffordable housing, poor energy efficiency or high fuel prices.

In England, households are assessed by the Low Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE) metric and considered fuel-poor if the Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of the property is D or below, and

if their remaining income after heating costs has fallen below the poverty line.

The proportion of households in fuel poverty has risen from 13.1 percent in 2021, and is projected to increase further to 14.4 percent in 2023. Meanwhile, the End Fuel Poverty Coalition claims

30.3 percent of all households in England spent more than ten percent of their income on energy bills last year.

A variety of household characteristics drastically change the likelihood of being considered in fuel poverty, from region to dwelling type to resident ethnicity. One of the most obvious attributes is particularly telling: 44.6 percent of those in the lowest income decile fell into the group last year.

The contrast across the country is stark.

The West Midlands was found to be the region with the highest proportion of fuel poor households at 19.2 percent - more than double the 8.6 percent rate in the South East.

Nearly half a million homes in the West Midlands (489,000), the North West (486,000) and London (471,000) were in fuel poverty in 2022.

In terms of the average fuel poverty gap - the reduction in fuel costs needed for a household to not be in fuel poverty - was highest in the South West, at £521. The nationwide average is £338, up 33 percent on 2021's £254.

Rates of fuel poverty were also found to be higher in rural areas - 15.9 percent of all country homes - than in urban areas (13.4 percent).A spokesperson for the Department for Energy Security & Net Zero said: "We know it's been an incredibly tough time with families struggling to meet energy costs, as these figures show. While no national government can control the global factors pushing up the price of energy, we've sheltered households from the full exposure by paying around half of a typical household's energy bill over this winter."

"And we'll continue to support households even as the milder weather kicks in, with the Energy Price Guarantee set to save the average household £1,000 up to June. At the same time, we're spending billions to boost the energy efficiency of homes - which has seen 145,000 households move out of fuel poverty."

Those living in social housing were just under five percentage points more likely to be living in fuel poverty than those in the private sector, with rates of 17.3 and 12.5 percent respectively.

Fuel-poor households were also more likely to be in converted flats than any other dwelling type - almost a quarter (24.8 percent) of the total falling into the category. The rate for detached houses was just 7.6 percent.

The features of the occupants also have a large impact.

Working couples with no dependent children have just a 6.9 percent chance of being in fuel poverty. For couples with children, this rises to 17.2 percent. For a lone parent the rate soars to 26.2 percent.If the person of reference in the household belonged to an ethnic minority, the fuel poverty rate in England was 20.3 percent. If they were white the comparable figure was 12.4 percent.

If the referent was in full-time work, there was a 9.3 percent chance of being in fuel poverty.

For the unemployed, this rises to 38.2 percent, but for those in full-time education, it was an even higher 39.7 percent.In February 2021, the Government published "

Sustainable Warmth: Protecting Vulnerable Households in England" - its strategy for ending fuel poverty. Its headline target was to "ensure that as many fuel-poor homes as is reasonably practicable achieve a minimum energy efficiency rating of band C, by 2030."

There was no increase in the share of households above this threshold in 2022, with just a slim majority of low-income households (52.8 percent) living in a property with an EPC rating of C or above.

According to charity

National Energy Action (NEA), the Government's target will be missed by 300 years. NEA Chief Executive Adam Scorer said: "Over 3.2 million households in England are in fuel poverty

according to Government data released today but the worst of the energy crisis is not represented - people are being forced to self-disconnect, struggling with ice on the inside of their windows and living with damp and cold.""And

the situation will not get better.

From April the average annual bill will rise from £2,500 to £3,000 and that means without Government intervention - both for efficiency measures and financial support with bills - the number in fuel poverty will continue to rise."

Ruth London, from Fuel Poverty Action, commented:

"Public anger is intense and support is growing for a whole new system, Energy For All. This would mean no standing charges, a free band of essential energy so that no one freezes to death with excess energy use charged at a premium.

"This would be funded by windfall profits and end to fossil fuel subsidies with accelerated energy efficiency and renewables expansion to reduce cost of the proposals."

Comment: See also: